Hole in the Clouds

Sep 8, 2009

In the summer of 1913, Hazel Reiber winds up for a pitch near the ocean in the big sandlot at Long Beach, Long Island. Her bathing costume looks skimpier than the outfits many women wore back then, but her boots would do just fine for a professional wrestler.

That is a baseball in her right hand, but I'm guessing--hoping--that the person she's throwing to is not swinging a bat. It doesn't look safe for slugging thereabouts.

sports

New York

vintage

Long Island

beach

baseball

Hazel Reiber

(Image credit: Bain News Service, shorpy.com)

Aug 31, 2009

Breitner-like.

It means weather like what we see in this early twentieth-century photo of Amsterdam by George Hendrik Breitner. Somehow, the laundry and the grainy gray make the Netherlands look less tidy and perfect than we've come to expect.

Breitner's name entered the Dutch vocabulary in reference to a kind of weather--dark, damp, chilly, misty, gloomy--based on his well-known late-ninteenth-century paintings of the Dutch landscape. But in 1996, a drawerful of photos by Breitner (including this one) was discovered in somebody's attic in Amsterdam, and it turns out that the atmosphere in Breitner's photographic landscapes is just as in his paintings. Breitner-like.

landscape

vintage

Europe

Amsterdam

George Hendrik Breitner

via shorpy.com)

(Image credit: George Hendrik Breitner

Aug 28, 2009

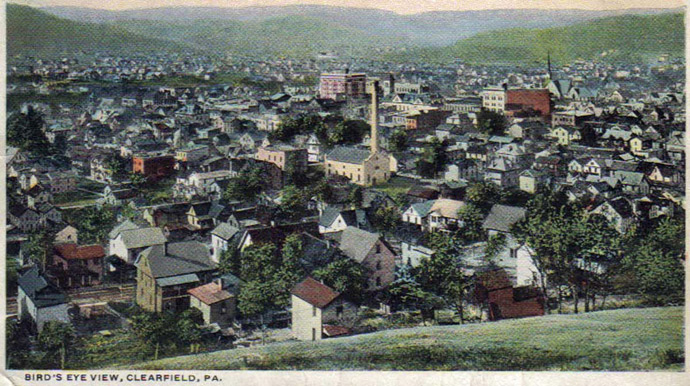

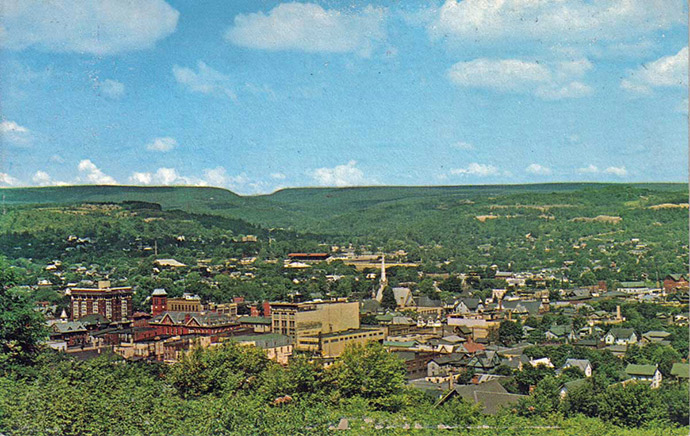

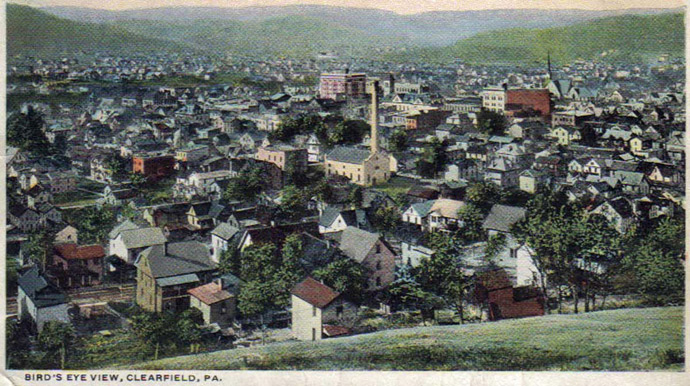

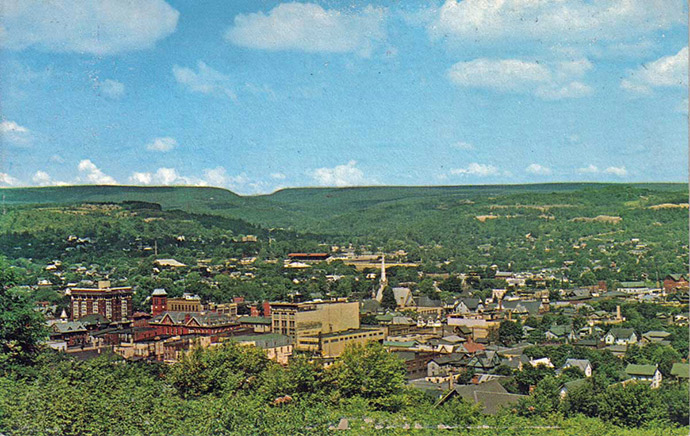

The town of Clearfield in the hills of west-central Pennsylvania grew little or not at all between 1910--when a photo was taken from a nearby slope, painted by hand, and reproduced lithographically--and the 1960s--when a color photo taken from nearly the same spot was published as a picture postcard. Town population still stands at about 6,000 today. The dark church steeple in the upper right of the older picture is the white steeple in the center of the more recent view.

Apparently, the years have not been kind to Clearfield as far as the artistic level of its town boosters' bird's-eye views is concerned--but that's typical; a lively American artistic genre has been poorly replaced, first by Kodachrome and more recently by Google Earth.

Time marches on, however, in Clearfield. In 1977, the town became the home of Denny's Beer Barrel Pub, where the cook "enjoys making burgers bigger than your head, all the way up to the insane 123-pounder."

landscape

bird's eye view

vintage

Denny's Beer Barrel Pub

Clearfield, Pennsylvania

Aug 27, 2009

This 1954 photo was part of a magazine advertisement. Makes me want to buy a Buick, sort of--must be the pearls and the black glove, and that little tiny trunk key.

vintage

pearls

car

Buick

(Image credit: unknown)

Sep 17, 2009

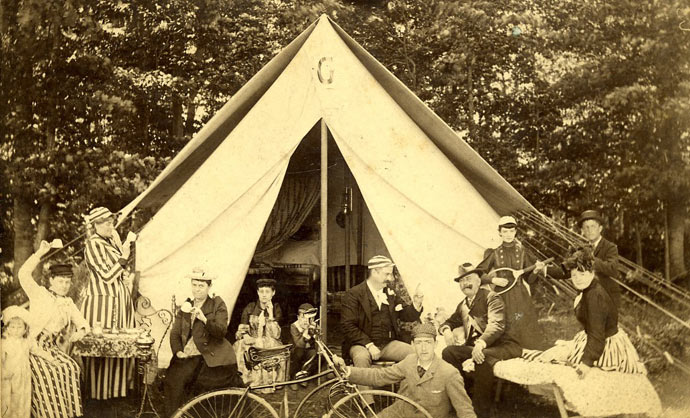

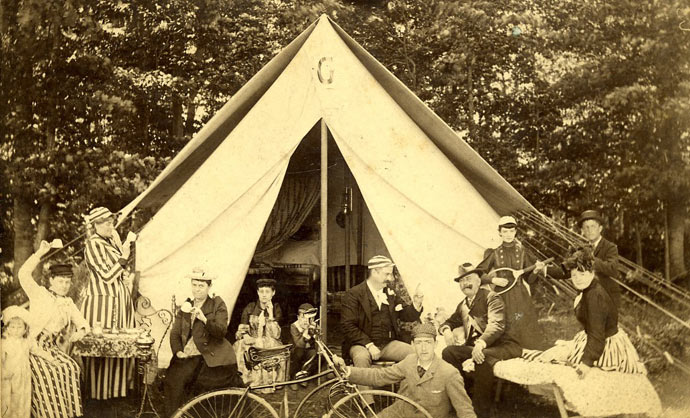

Family camping in 1891 was what it was--the striped skirts, the upside down teacups, and most notably, the tennis racket played as a guitar. "These people are related to me," observes West Coast painter Amy Crehore, who found the old snapshot in a box of old family treasures.

The woman making music on her tennis racket may be particularly closely related to Crehore, who often paints scenes in which women are playing ukeleles. Here is one of her recent works, "Monkey Love Song."

vintage

family

camping

Amy Crehore

(Image credit: Amy Crehore family)

Sep 25, 2009

I'm sure there are more than two stories that can be linked to this street corner in Washington, D.C., but I see two in the photo.

The first one is a tale of two gas stations: The year is 1925, cars have only been on the road for a few years, but already here we see a derelict gas station, rundown, boarded up, the gas pump already removed. The parked car may or may not be a junker, but it's not much of an advertisement for the carwash service. But look across the street, at the far right edge of the picture. You may want to enlarge the photo to see full detail. (Or ask me to send you the very high-resolution original photo, 2.6 MB file.) That's a brand spanking new Standard Oil Co. gas station, the original category killer--so Story #1 is about how Mr. Rockefeller probably put this guy out of business and blighted this corner of my hometown.

Story #2 is about the corner itself. It's 2nd Street and Massachusetts Avenue NW, which is stunning to those of us who feel they know Washington. Mass Ave is one of the businest streets in the city, and the intersection is in the heart of downtown, about four blocks from Union Station. In 1925, there wasn't even a line painted down the middle of Mass Ave. Furthermore, based on the trees and their shadows, we can deduce that the picture was taken in late afternoon or early evening--rush hour. Perhaps it was Sunday, but still--the wide-open emptiness is not consistent with our notions of a major downtown artery. This scene feels like a small town, or the edge of a city, not the center of the nation's capital, just eight blocks from the U.S. Capitol building.

What's there today? Nothing. Grass and a couple of curving walkways--I think the local term is pocket park. It's an unusual park, however, built on the air rights above the I-395 freeway as it dives underground just north of Massachusetts Avenue. Rumor has it that behind this park, they're planning to build offices and even stores and apartments, all on the I-395 air rights. This is said to be the biggest construction project in Washington right now that hasn't been suspended--maybe it hasn't been suspended, but it's not yet what they call shovel-ready.

And for what it's worth, the Standard Oil station isn't there any more either; that corner is occupied by a medium-sized brick office building that serves as Washington headquarters for a business association.

vintage

Washington, DC

cityscape

Standard Oil

cars

(Image credit: Nat'l Photo Co., via Shorpy)

Aug 11, 2009

When the Custom House tower opened in 1913, tthe zoning code for the city of Boston limited building height to 125 feet. Because the Custom House was a federal installation, it could flat-out ignore the restriction; this tower is 496 feet high, making it the tallest building in Boston until 1964. The exterior is essentially unchanged to this day, though the interior has been drastically redesigned. It's now a time-share condo complex operated by Marriott.

Underneath the tower is a large Doric temple built in 1847, an imposintg structure that housed the warehouses and regional financial offices of the customs service. Most of the federall government's income in those days came from import levies, so in port cities such as Boston, custom houses were typically the nicest buildings in town.

In this picture, the clocks at the top of the tower have no hands. This is probably because repairs were being attempted; the wooden minute hand was so big and heavy--22 feet long--that the clock mechanism struggled to push it up from the 6 toward the 12, often failing. Until the hands were replaced with plastic a few years ago, the clocks rarely kept good time.

vintage

cityscape

Boston

Massachusetts

tower

(Image credit, Library of Congress, via Shorpy)

Oct 1, 2009

Obviously, this picture was taken on a Monday. The scene is the tenement backyard at Park Avenue and 107th Street in New York, probably in the year 1900.

Setting up these clotheslines was not a trivial task, especially on the higher floors. A man would come around calling out "I climb poles!" and for about 25 cents he'd climb up and run the rope out over the pulleys. He also sold rope and pulleys, but if you'd planned ahead and bought them from the hardware store, you could save a few cents.

Notice the train track at the bottom of the photo--I'm guessing the whites were whiter at the far end of the block. Just on the other side of the tracks is the building where baseball player Lou Gehrig grew up, a few years after this picture was taken.

I suggest viewing this image as large as possible, so you can peep into the windows.

New York

vintage

cityscape

tenement

laundry

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co., via Shorpy)

Oct 9, 2009

After some of you fussed yesterday about the lack of a story to go with the picture, I've got a story for today--the beginning of a two-part story, in fact. It could be classified as another entry in an irregular series dealing with places I've never been to and probably have no business writing about.

The picture looks down on the harbor of Duluth, Minnesota, in 1905, from a vantage point near the top of the city's new inclined railway. The railway may look like part of the town's extensive industrial infrastructure, but it was actually a people-mover, built by the city in the late ninteenth century at the instigation of real-estate developers who wanted to sell houses high up the hill above downtown. "The Incline" operated for about 50 years, powered by an electric motor at the top and working a little like an elevator, with a dummy-car counterweight on the left track that moved downhill when the passenger car on the right track was pulled uphill.

What I didn't know about Duluth could fill several hard drives. Here's what little I did know: it's Bob Dylan's hometown, and the winters are ridiculously cold. The Dylan factoid is only partly true--yes, he was born in Duluth, but he really grew up a hundred miles north in Hibbing, Minnesota, a mining town that had to relocate itself because the mine got too big. As for the factoid about Duluth winters: yes, of course, they really are brutal, with a spell of forty below or worse most years. But "the Incline" was so steep that snow never piled up too deeply on the tracks, not even during blizzards.

As for the things I didn't know about Duluth: Number one, around the time of this photo, it was among the wealthiest towns in America, claiming more millionaires per capita than anyplace else. It thrived because of a confluence of geology, geography, and the highest technology of the era.

In the 1870s, northern Minnesota had a gold rush; no commercially significant gold was ever found, but the prospectors did stumble on high-grade iron ore in the hills north of Duluth. They'd discovered Minnesota's Iron Range, one of the largest iron deposits on earth and the subject of tomorrow's part of the story.

By the 1880s, Duluth and the Iron Range were connected by railroad. Ore from the mines was off-loaded from the trains at Duluth onto large ships. The ships would have been stuck forever in Lake Superior, unable to exit, had not construction been completed around that time on the mechanized locks at Sault Ste. Marie, which helped ships to descend the 21 feet between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. The ore ships from Duluth sailed a thousand miles across the Great Lakes to the newly constructed steel mills in Indiana and Pennsylvania and Ohio and New York, where newly invented Hulett machines automatically unloaded the ore from the ships and dumped it into blast furnaces. As soon as the new steel cooled, it was snapped up by new factories assembling cars and tractors and locomotives and wringer washing machines and everything else that used to be made in America.

All cities that boom must implode. (I don't know if that's true, but it sounds about right.) What happened to Duluth was World War II, with its extreme demand for iron ore to build tanks and planes and ships to replace the ones that were being consumed in battle. The Iron Range couldn't keep up; huge wartime scrap-metal drives were needed to supplement the mines.The track of the inclined railway was itself torn up and sold for scrap. By about 1950, all the good ore in the entire Iron Range had been clawed out of the earth and shipped away through Duluth. The city languished.

Fortunately, scientists at the University of Minnesota had seen this coming and were hard at work on a work-around. Within a few years they came up with a way of using the Iron Range's low-grade ore, called taconite, Taconite isn't as valuable as the old stuff, and it has to be compete with cheap ore now coming in from places like Brazil, and anyway, most of the old steel mills and factories are no longer operating, but Duluth remains a fairly active port to this day. Last year, it handled 500,000 railroad carloads of taconite. The railroad also brings grain to Duluth from all across the northern Plains, which also gets loaded there onto ships.

But nowadays, more valuable than wheat or taconite to Duluth's economy are tourists. Now that the smoke is gone from the old ore processing works, the city's scenic lakeside setting attracts vacationers interested in all the outdoor activities of the north country: boating, fishing, hunting, snowmobiling, and so on. Along the top of the hill is a string of popular state parks. Even the sand bar that protects the harbor, seen in the distance in the photo, is now a park, and also a seaplane base. Visitors are buying up the old houses on the side of the hill to use as vacation homes.

Somewhere in the city, I can't figure out where, is a trail they've named the Bob Dylan Walking Path. Must be near Highway 61.

vintage

Minnesota

Lake Superior

geology

Duluth

Bob Dylan

(Image credit: Detroit Photographic Co., via Shorpy)

Oct 14, 2009

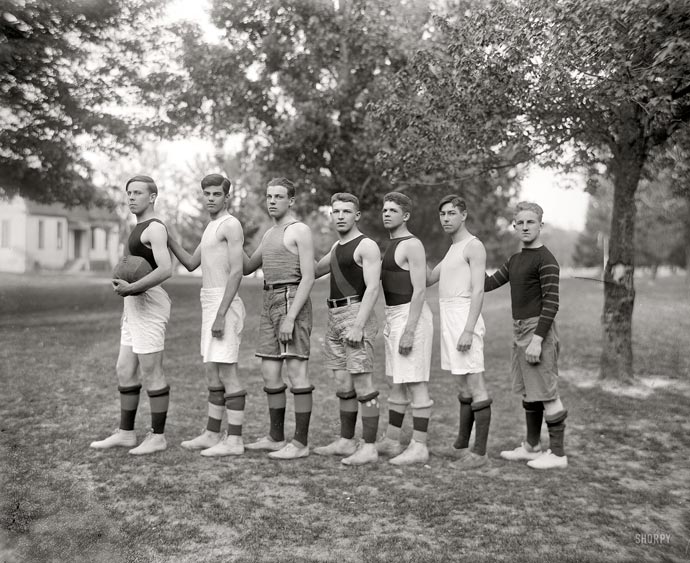

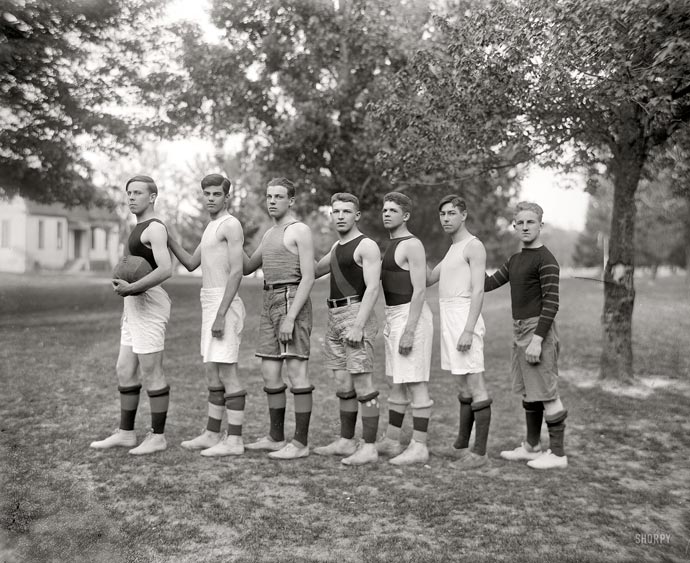

This is the 1905 varsity basketball team from Charlotte Hall Military Academy in St. Mary's County, Maryland. Sylvester Stallone was a Charlotte Hall boy, shortly before the school closed in the 1970s.

In 1905, basketballs had laces like footballs, and dribbling was very tricky.

sports

vintage

Charlotte Hall

Maryland

(Image credit: Harris & Ewing glass plate, via Shorpy)

Oct 28, 2009

Dorothea Lange photographed this woman in a migrant farmworker camp in Klamath County, Oregon, in 1939. According to Lange's notes, the woman was a young mother, originally from El Paso, Texas, who had just finished her washing.

vintage

migrant farmworker

Oregon

(Image credit: Dorothea Lange

Farm Security Administration)

Nov 13, 2009

Amidst all the screaming and snarking of the blogosphere is a website that's sweet and wonderful: MyParentsWereAwesome.com

Anybody can send in pictures of parents (or grandparents) from back in the day. I'm going to send in pictures of my parents, because they're still really awesome, and I expect all of you to do the same.

Here are three sets of parents from the site:

Thelma and Reuben, looking at each other--submitted by Seth

Jonathan and Virginia, seated--submitted by Rob

Kathi and Kenney, with the guys in the band--submitted by Ryan

vintage

parents

Nov 15, 2009

All right, not seventy-six, but definitely one trombone in this band-sextet-plus-string-quartet from the U.S. Marine Corps Band in 1910. And a double-belled euphonium--for real! Over there at the right.

Do you remember the double-bell euphonium, from "Seventy-six trombones" in Meredith Willson's Broadway show "The Music Man"? I'd thought it was a joke, a made-up instrument that the ignorant folks of River City, Iowa, would believe was real. But I guess it was actually more of an in-joke, a real band instrument of the era, with a name so silly that only the cognoscenti would believe it. As always, I ain't no cognoscenti.

This photo is from the middle of the era celebrated in "The Music Man," when towns all over America built bandstands in the park and organized their own brass bands. In the cities, commercial brass bands were making big money. John Philip Sousa, everybody's favorite bandmaster and composer, had joined the Marine Band at the age of thirteen and conducted it long enough to play for five presidents. But before the turn of the twentieth century, Sousa left the Marines to seek his fortune with the baton of his own Sousa Band, which was wildly successful and became the first American musical organization to tour Europe. In the 1920s, the piccolo player in the Sousa Band was none other than Meredith Willson, who who spent the next thirty years working on music and lyrics for "The Music Man," which finally debuted in 1958.

Today's Marine Band is still "The President's Own" and the premier ensemble of the U.S. military, which claims to employ more musicians than any other organization on earth. The band uniforms haven't changed much in the past ninety-nine years, though the shoes are much shinier nowadays.

Oh, and here's "Seventy-six Trombones," as performed by the trombone choir of Anchorage, Alaska.

vintage

music

John Phillip Sousa

Meredith Willson

Marine Band

The Music Man

double-belled euphonium

(Image credit: Harris & Ewing glass plate, via Shorpy)

Nov 18, 2009

This mid-1950s photo, according to the little boy with glasses in the middle of it, records the moment he chose his life's work. His older brother, at left, is showing a photo album to a family friend. His older sister shot the picture.

What is the little boy thinking? He claims that the idea going through his mind is: "All I have to do is take some pictures, and everybody will pay attention to me."

I don't know who he is; he submitted the photo and many others to Shorpy, under the username tterrace.

vintage

1950s

(Image credit: tterrace, via Shorpy)

Nov 28, 2009

Jack Delano's 1940 photo of Pittsburgh has a cinematic feel to it, as the lady on the staircase descends into a dark and cold and spectacular kind of hell. That particular hell--with sulfurous fumes belching from roaring steel mills--went south a generation ago, abandoning western Pennsylvania to rust and poverty. Somewhat remarkably, the city has stirred from its decline and reinvented itself as a clean and shiny, almost high-tech sort of place. But all along, the sons and daughters of Pittsburgh have been growing up into American image-makers, people who have shown us what we look like, or would like to look like, or hope to God we never ever look like. Fred Rogers, with his sweater and sneakers and perfectly detailed little world of children's TV--wasn't Pittsburgh's first or last cultural chronicler.

Early on, there was Stephen Foster, of Swannee River and Camptown Races fame, and then the painter Mary Cassatt, the modernist Gertrude Stein, and the Tarzan, Johnny Weissmuller. Some of the Pittsburghers have worked right up to the cultural edge--Andy Warhol--and some have walked us up to the brink, where we could glimpse a frightening future--Rachel Carson.

Most notable, perhaps, were all the guys who played football, generation upon generation of Pittsburghers who were big and tough and fast and focused: Johnny Unitas, Joe Namath, Mike Ditka, Larry Brown, Nick Saban, and way too many others

Then there were those who worked the cultural currents of the times: e.g., Bobby Vinton, Lou Christie, Charles Bronson. And the ones who have risen above their times, soaring elegantly: Gene Kelly.

But who took the neighborhood in this picture and warped it into a dark corner of the American consciousness? Back in the early days of television, Fred Rogers hired an imaginative young assistant who moved on to Hollywood and directorial fame and fortune--guy by the name of George Romero--whose first big hit opened a seam of movie-dom that has been dug ever deeper to this day: Night of the Living Dead.

And for what it's worth, Pittsburgh still has more than 700 staircases officially registered as city streets.

vintage

Pennsylvania

winter

Fred Rogers

1940s

Pittsburgh

George Romero

(Image credit: Jack Delano)

Jan 9, 2010

The first big railroad operation in the world was the Grand Trunk, a Canadian company that started up in 1852 with a line from Portland, Maine, to Montreal, Quebec. It is hard to fathom today why anybody would invest money in rail transportation between Portland and Montreal--the two cities nowadays have little to do with one another, and there is little travel or freight transport between them.

Back in 1852, however, both cities were important ports. Montreal, which sits closer to Europe than any U.S. port, was a major terminal for trans-Atlantic shipping. Portland supplied lumber to the world and was the northern terminus of coastal U.S. shipping routes.

And back when railroad technology was a newfangled thing of uncertain commercial value, trains were initially imagined as a means of extending sea transport. A train could load up in the port of Montreal with European goods and deliver them to the port in Portland, from which they could be sent by ship to any of the fast-growing markets in cities along the eastern seaboard of the United States.

The Canadians who thought up this scheme became wealthy men. They eventually expanded the Grand Trunk to Toronto, Chicago, and points west, and they added a second New England line down through Vermont. Within a couple of decades, imitations of the Grand Trunk Line had been built all over North America, stitching the continent together with railroads.

This picture shows the port of Montreal around the time the railroads were starting up. Today, Montreal is the busiest container port in the world and also handles grain and other products from central Canada and the midwestern United States. Most of the grain still gets to the port by train.

Portland's port handles more tourists than anything else these days, though South Portland remains active as a terminal for Mideast oil shipped to the United States. The oil is pumped from tankers into a pipeline that closely follows the old Grand Trunk route up to Montreal, where it is refined to make gasoline and other petroleum products.

vintage

Montreal

port

Jan 10, 2010

The Grand Trunk Line went bankrupt in 1920. Cost overruns on its expansion to the West Coast stressed the company, and its route planning out west proved unfortunate, too far north to compete with the fledgling Canadian National Railroad, which eventually absorbed it. The Grand Trunk's U.S. lines were assigned to a holding company that used the Grand Trunk name, but they too declined and faded in the mid-twentieth century along with the railroad industry in general.

The Grand Trunk station in Portland, on India Street near the waterfront, was demolished in 1948. These pictures actually show a different Portland train station, Union Station on Congress Street near St. John Street, which handled southbound passengers and freight. Union Station opened in 1911 and was demolished in the1960s to make way for the I-295 highway.

Portland lost an elegant building that day--the current Amtrak station is basically just a corner of the bus station lobby--but by all accounts, the destruction awakened people to the importance of historic preservation. And though it couldn't have been foreseen in the 1960s, when urban renewal was thought to lead to future glory for America's cities, Portland's old buildings and cobblestone streets have turned out to be what saved this town--people have learned to make money off of "quaint."

Portland

vintage

Maine

railroad

demolition

Union Station

train

Jan 11, 2010

When they built the Grand Trunk line from Portland to Montreal in the early 1850s, they had to figure out a way over or around the White Mountains in New Hampshire. They ran the tracks up the Androscoggin River valley past the tiny village of Gorham, just eight miles north of 6,200-foot Mount Washington. Gorham became the railroad maintenance and service center, and this late-nineteenth-century birdseye view of Gorham shows the extensive railroad yards developed there.

Anyone who has been to Gorham, however, will notice something a little odd about this image of the place. The mountains in the background look low and unprepossessing, just some handsome, rolling topography off in the distance. Actually, they loom crazy big over the town, with Mount Washington in particular filling the sky and dominating the view almost like an Alp. Gorham is less than 800 feet above sea level; the peak of Mount Washington is more than a mile higher. Perhaps the artist (and/or his patrons in town) feared that big mountains might scare people away from Gorham. Gentle country would look more hospitable.

But the railroad that created Gorham eventually brought tourists to the hills, and today the town survives as a jumping-off point for vacationers in the White Mountains. An artist publishing a twenty-first-century birdseye view of the town would probably want to emphasize the mountains, maybe even drawing them bigger and steeper and closer than they really are. Wild, dramatic country is what the people want nowadays.

Trains don't stop here any more, but there is a railroad museum.

Mt. Washington

vintage

New Hampshire

birdseye view

railroad

Gorham

White Mountains

Jan 16, 2010

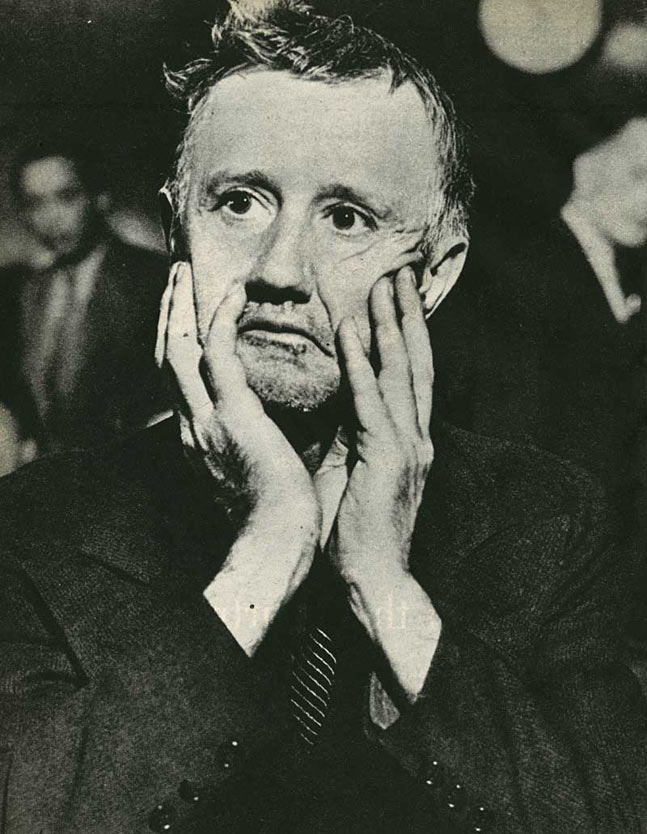

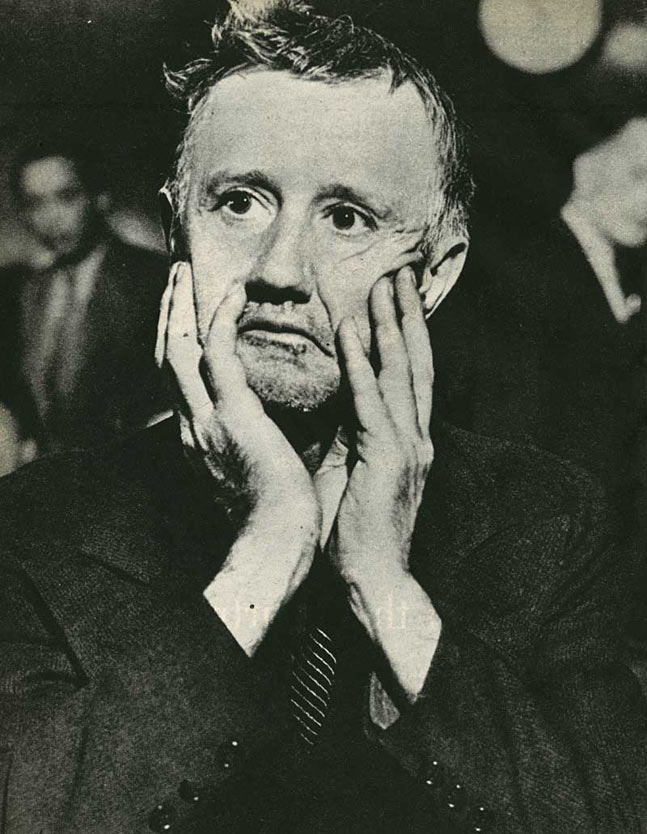

In April 1947, this photo led off a Coronet magazine spread on taces of people accused of murder and other crimes.. "For men who break or ignore the law, there is no hiding place, no turning back," according to the caption. "His hands eloquently expressing self-pity, this man confessed to killing two people. 'I wish I'd kept still,' he said."

Other photos and captions from the piece are posted here. H/t to John Stein.

vintage

Coronet magazine

crime

portrait

1947

courtroom

Jan 19, 2010

This photo has been used on the cover of paperback editions of Wuthering Heights, but it's really a self-portrait of a Philadelphia lampmaker named Robert Cornelius. Cornelius apparently didn't comb his hair for the camera, but he can be forgiven because he probably thought the picture wouldn't really come out anyway. He made the daguerrotype in November 1839 out in the yard behind his family's lampworks, on Chestnut Street in Philly, and it is believed to be the first ever photographic image of a human face.. On the back of the picture, Cornelius wrote "The first light picture ever taken, 1839." Three months later, he opened the first ever photographic portrait studio, but later census reports suggest that he eventually went back into the family lamp business.

A competing claim for portrait primacy has been put forth for a French daguerrotype made by Daguerre himsel, perhaps in 1837, which would be two years before he announced his process for making "light pictures." In 1838, Daguerre claimed in a letter that after several attempts at portraiture, he'd had one success, and some experts believe that one early success is a recently discovered portrait of the painter Nicolas Juet. Early photographic portraiture was difficult because Daguerre's technique required extremely long exposure times, so long that in order to stay perfectly still people had to adopt rigid, artificial, inelegant poses.

Cornelius, who had specialized in silver-plating lamps for the family business, worked on the chemistry of Daguerre's silver-based process and may have achieved some refinements before he made his self-portrait. He is known to have added bromine to the formula. His pose here looks strikingly casual compared to most nineteenth-century portraits, though the arms crossed over his chest may have helped him remain motionless, probably for at least two minutes and perhaps for as long as five minutes.

He does appear to have just stepped out of Wuthering Heights.

vintage

Robert Cornelius

Philadelphia

daguerrotype

Daguerre

(Image credit:Robert Cornelius, via Shorpy)

Jan 27, 2010

He's delivering milk to the Restaurant Louisiane on Iberville Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans, circa 1903.

Just behind the milk wagon--look through the wheels--is a jumble of something spilled on the sidewalk at the curb. Another wagon must have recently stopped by there, delivering coal. Somebody from the restaurant will have to come out and scoop it up.

vintage

streetscape

New Orleans

Louisiana

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Company

via Shorpy)

Jan 30, 2010

In 1935, when my father's parents Rose and Charles Horowitz celebrated their thirtieth anniversary, the basic fact of life in America was the Great Depression. Still, to mark the occasion properly, you had to dress up and sit for a formal portrait.

That's Rose and Charles in the middle, of course, with my father, Bobby, the baby of the family, on their laps. He is 85 now and may be the only person in the picture who's still alive. Fortunately, he noted who's who and described everybody for posterity--the woman at the far right, for example, is "cousin Hattie, who became the first radio cab dispatcher in Baltimore."

Three of my father's four siblings are shown here, with their spouses, along with assorted relatives and friends.

Sitting next to my grandmother is her sister Bessie, and standing behind Bessie is Uncle Eli, the subject of today's post. Back in eastern Europe before the turn of the century, Eli had been conscripted into the czar's army and ordered to Siberia; he deserted and somehow found his way to Philadelphia instead, There, he got a job as a furrier, married Bessie, and raised five children. They were poor; my father recalled that in Eli and Bessie's house, he had to be very careful not to use too much soap when he washed his hands.

Some years after this picture was taken, when Eli and Bessie were celebrating their own fiftieth anniversary, Eli went out on the floor with all the young guys and danced the Kazachok, the Russian squatting-and-kicking dance. The family story is that he kicked as hard and danced as fast and lasted as long as anybody half his age. He had a talent for enjoying life, including his schnapps. One of his sons became a doctor, who warned his father not to drink too much; the story is that when the son ordered him to cut back to one glass a day, Eli said fine, but he made sure that his one daily glass was a huge water-tumbler-sized drink. Whatever, he outlived his son the doctor.

Eli had a one-word retirement plan: fishing. And that's exactly what he did; when he was finally too old to stay at work sewing furs, he and Bessie moved to Atlantic City, where every morning he woke up, walked down to the beach, and went fishing. He was in his nineties when I first met him, still the life of the party, and still fishing.

vintage

anniversary

Horowitz family

Uncle Eli

Baltimore

1935

Feb 14, 2010

In the late 1940s, a photographer visited a school in the village of Paro, a day's walk up into the mountains from Thimphu, the capital city of Bhutan. One of the students in this picture recorded the occasion in his journal: "All we heard was a click, and then the next day we were amazed to see our images had materialised on paper."

Bhutan remained one of the world's most isolated countries until the 1990s, when its king announced a new economic policy, which he called GNH: Gross National Happiness. Some Western developments, including television, would be allowed in, even encouraged, but others, such as smokestack industries, would be kept out. Bhutanese life would be integrated with the rest of the world only insofar as the changes increased people's happiness in Bhutan. A new government ministry was created to measure GNH.

And so it came to pass that in 2008, upon recommendation of the ministry of happiness, the kingdom of Bhutan became a democracy, with its leaders chosen by popular election. The American experience evidently was not cautionary enough. Or something.

So far, Bhutan still ranks at the top worldwide in indices of national happiness, according to people who try to measure this sort of thing. The Bhutanese people are said to be as happy as anyone anywhere--and far happier than people in other parts of the world where per capita income is as low as it is in Bhutan. The average Bhutanese person gets by on about $l,000 a year.

The village of Paro now hosts an annual international cricket tournament. If cricket is required for high GNH, we Americans are surely doomed.

vintage

Paro

Bhutan

(h/t: Katrin Maldre)

Feb 17, 2010

In 1900, Mulberry Street in lower Manhattan was the heart of Little Italy, where life was apparently lived out in the open, right in the street. Nowadays, cars instead of people dominate the street, and the people have retreated indoors, where apartments are much less crowded and much more likely to have indoor plumbing.

Click on this picture to see a much larger version, which you can mouse around in to appreciate the details of life in New York a century ago: the vegetable carts, the guy with a glass of beer in the middle of the street, the boy with his schoolbooks, the Banca Malzone, the aprons and wagons and fire escapes and . . .

New York

vintage

Manhattan

streetscape

Little Italy

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co., via Shorpy)

Feb 28, 2010

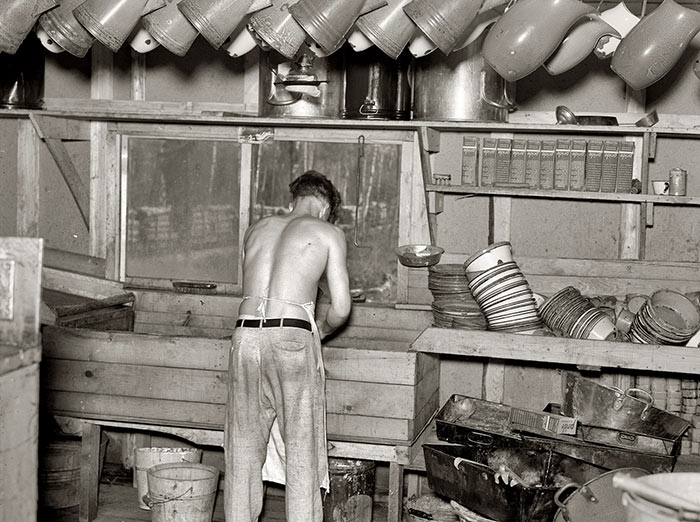

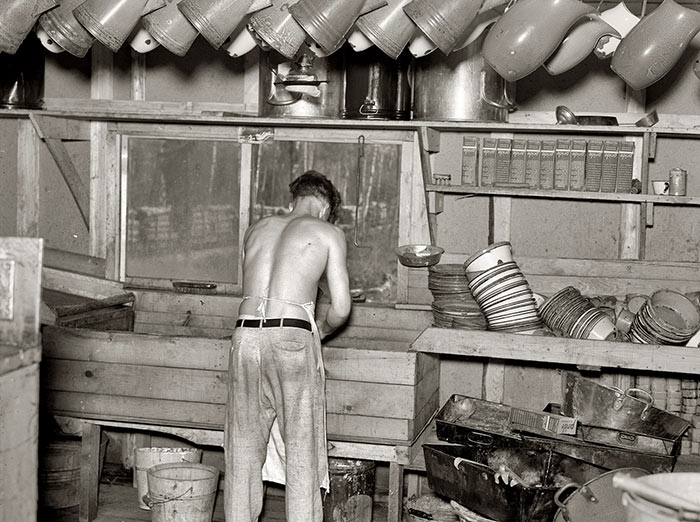

In the cookhouse at a logging camp near Effie, Minnesota, cleaning up after dinner was obviously a job that took a little while; the work might have gone faster if only the place had had running water.....

Russell Lee took this Farm Security Administration photo in 1937.

Looks like the dishwasher's only company may have been the naked woman in the little picture tacked up on the window frame.

vintage

Minnesota

Farm Security Administration

kitchen

Effie

(Image credit: Russell Lee, FSA)

May 27, 2010

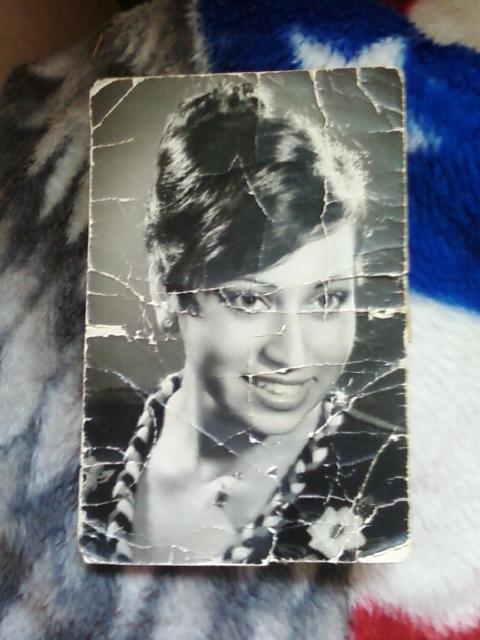

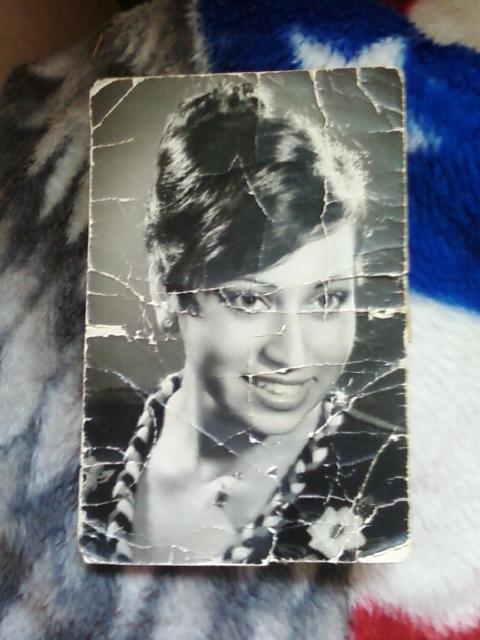

Someone who identified herself only as Lynzee submitted this photo to the My Parents Were Awesome website. The only label on the picture is: Esther.

vintage

Esther

mother

Jun 21, 2010

It would be understandable error if, assuming you had nothing to go on but this one pair of pictures, you came to the conclusion that not much of anything really happened in Europe during the twentieth century.

The top picture shows the marketplace in Ghent, Belgium, in 1900; the lower photo was taken from the same vantage point in 2010. Of course everything in this part of town--the Korenmarkt--had already survived very nearly intact from about the 11th century until photography was invented and the streetscape could be snapped at the start of the 20th century. Presumably, nothing much was happening back then in that neck of the woods.

Except for Paris, Ghent was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe until the late Middle Ages. In the United States, old parts of cities tend to survive intact if the city experiences prolonged poverty, during which time redevelopment is economically unattractive. I don't know if the same dynamic accounts for neighborhoods that last a thousand years in Flanders and the rest of Europe.

vintage

streetscape

Ghent

Belgium

Jun 27, 2010

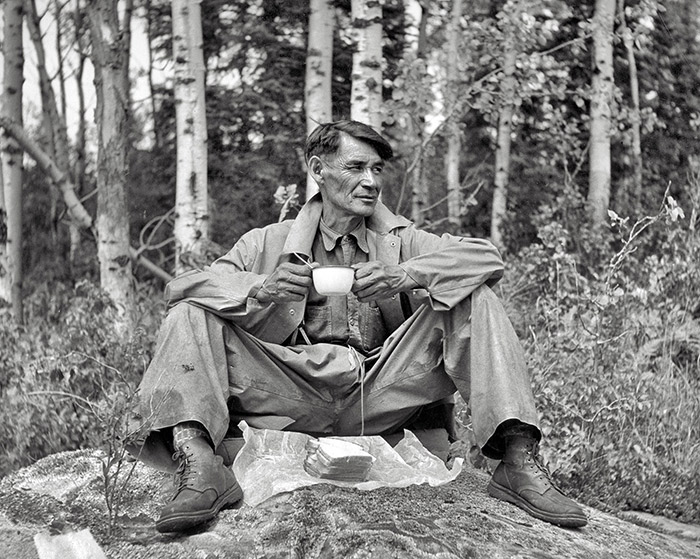

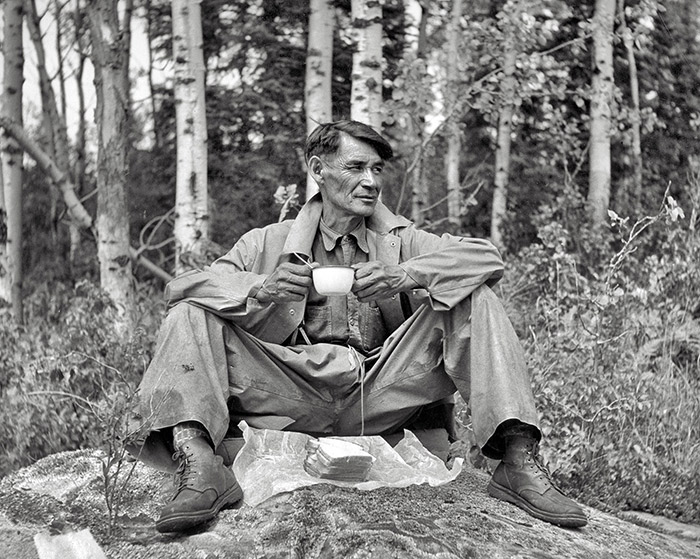

A man identified as "Canadian fishing guide" breaks for lunch on the shores of Lake of the Woods, Ontario, in 1952.

vintage

Canada

Ontario

Lake of the Woods

Jul 14, 2010

During the godawful heat wave of July 1901, nobody in New York was in a good mood, and everybody was mad at the ice companies. The reason was that hot summer weather was associated with both increased demand for ice and reduced supply of well water with which to make ice at the big ice plants in Brooklyn and the Bronx. So the ice companies started using city water to supplement well water, and on the hottest days, they used so much municipal water that taps literally ran dry all over town. New Yorkers complained loudly to their elected officials, but the ice industry also had ways of "communicating" with politicians.

Giving away a little free ice--bring your own dishpan--was a public relations gesture on the part of the ice-makers. But note that a police presence was necessary at the ice lines.

The heat wave of July 1901, with temperatures near 100 degrees, killed thousands of people. The misery was compounded by the deaths of thousands of animals, including horses pulling ambulances and fire engines, who dropped dead in their traces while responding to emergencies. Sanitation crews fell far behind in removing carcasses from the streets. Anybody who could afford to get out of town got out of town.

vintage

summer

streetscape

New York City

Aug 4, 2010

In 1905, when people went to the beach in Atlantic City, New Jersey, they wore funny clothes but had as good a time as beach-goers in 2010.

Many of the vacationers pictured here didn't own their own bathing clothes; they rented them from hotels or boardwalk establishments. If you click on this photo to see the enlarged version, you'll note that some of the bathing costumes are imprinted with the initials of the rental companies.

What about the boy and girl in the middle? Are they flirting? Or is he keeping her from fleeing the picture? Or . . . ?

vintage

beach

New Jersey

Atlantic City

crowd

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co., via Shorpy)

Oct 24, 2010

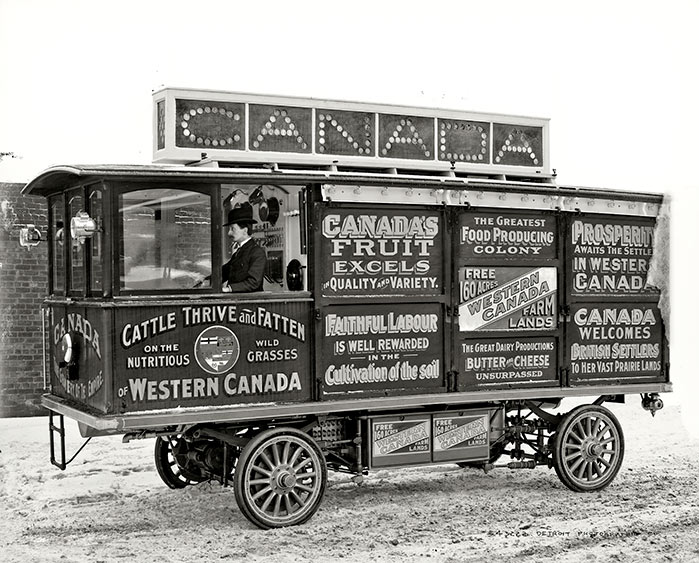

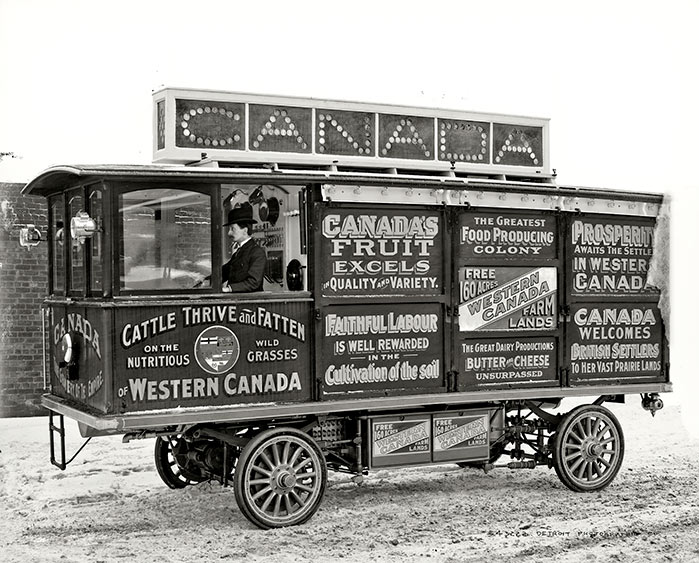

The stereotypical Canadian self-effacement apparently did not play a large part in 1905 in the design of this vehicle, a joint venture between the Canadian Pacific Railway and the governments of the brand new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The motor car was intended to travel the byways of England, promoting immigration to western Canada and, perhaps incidentally, ticket sales on the Canadian Pacific Railway and its trans-Atlantic steamship subsidiary.

The promotional message left out a few details. For one thing, although homesteaders could indeed claim 160 free acres of land, it cost $10 to file the claim, a sum many would-be homesteaders could not come up with after paying the Canadian Pacific for steamship and railway passage. Also, in the, um, bracing climate of the Canadian prairies, 160 acres was not nearly enough land to support a family.

So although the promotional efforts succeeded quickly in populating the prairies--this round of Canadian homesteading was closed off by 1914--most of the homesteaders were ultimately unsuccessful at farming and ranching. Among those few who could stick it out long enough to prove up on their claims, drought years beginning in 1920 ultimately chased them away. Today the Canadian prairie provinces (like the U.S. prairie states) are littered with ghost towns and empty farmhouses.

The vehicle pictured here was a hybrid, powered by electric motors at each wheel and a gas engine that heated a steam boiler. It never did work properly and was abandoned in London.

vintage

Canada

Canadian Pacific Railway

hybrid vehicle

Manitoba

Saskatchewan

1905

(Image credit: via Shorpy)

Aug 23, 2011

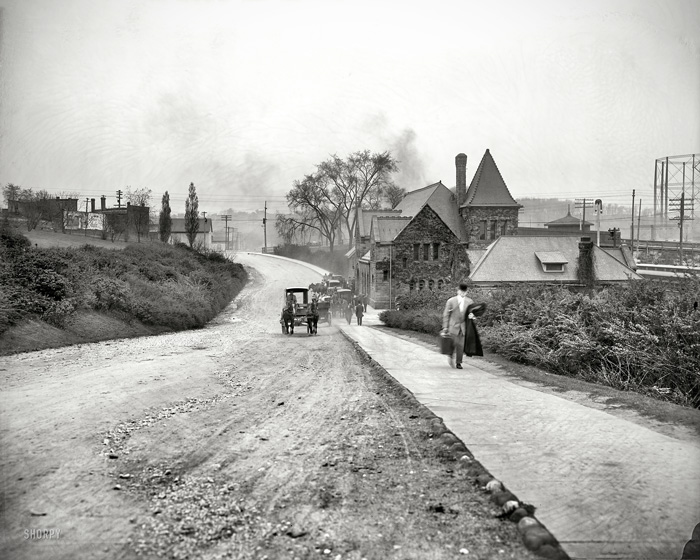

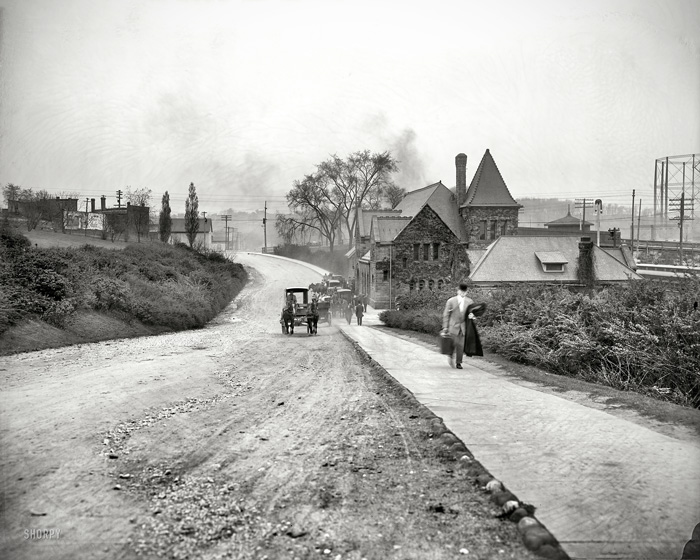

One evening in 1910, this man got off the train at the station in Ann Arbor, Michigan, picked up his coat and his briefcase, put on his hat, and headed up the hill toward home. It is possible, of course that what I referred to as the man's briefcase may actually be a salesman's sample case or a traveler's overnight case–but overall, that's my story and I'm sticking to it.

One evening in 1910, this man got off the train at the station in Ann Arbor, Michigan, picked up his coat and his briefcase, put on his hat, and headed up the hill toward home. It is possible, of course that what I referred to as the man's briefcase may actually be a salesman's sample case or a traveler's overnight case–but overall, that's my story and I'm sticking to it.

vintage

streetscape

Michigan

railroad

1910

Ann Arbor

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co. via Shorpy)

Nov 9, 2011

Somehow, Norman believes he can remember sitting in that chair and putting that balloon to his mouth, while Iris Quigley posed for the camera. The photo was probably taken in 1954, maybe 1955, in Iris's house, which was down the street from Norman's house in East Meadow, Long Island, New York. Great furniture, great dance moves, and we can hope those little baby teeth weren't too sharp.

Somehow, Norman believes he can remember sitting in that chair and putting that balloon to his mouth, while Iris Quigley posed for the camera. The photo was probably taken in 1954, maybe 1955, in Iris's house, which was down the street from Norman's house in East Meadow, Long Island, New York. Great furniture, great dance moves, and we can hope those little baby teeth weren't too sharp.

New York

vintage

Long Island

children

1950s

Norman

Iris

East Meadow

(h/t: Iris Quigley)

Feb 28, 2012

If you believe the banners in this ca. 1885 chromolithograph, the Standard Tip T.M. Harris & Co. boot comes with a double toe that is not only warranted and trade mark registered but also highest grade sole leather tip. It's not clear what the people frolicking in the ad have to do with double standard tip shoes, and it's not clear what a registered trade mark has to do with warranted highest quality, but what else is new. As my grandmother used to say: You believe that one and they'll tell you a bigger one.

If you believe the banners in this ca. 1885 chromolithograph, the Standard Tip T.M. Harris & Co. boot comes with a double toe that is not only warranted and trade mark registered but also highest grade sole leather tip. It's not clear what the people frolicking in the ad have to do with double standard tip shoes, and it's not clear what a registered trade mark has to do with warranted highest quality, but what else is new. As my grandmother used to say: You believe that one and they'll tell you a bigger one.

The shoe factory in the background was a building on Cherry Street in Philadelphia that was originally built for manufacturing chandeliers.

vintage

Philadelphia

shoes

lithograph

advertising

nineteenth century

Mar 28, 2012

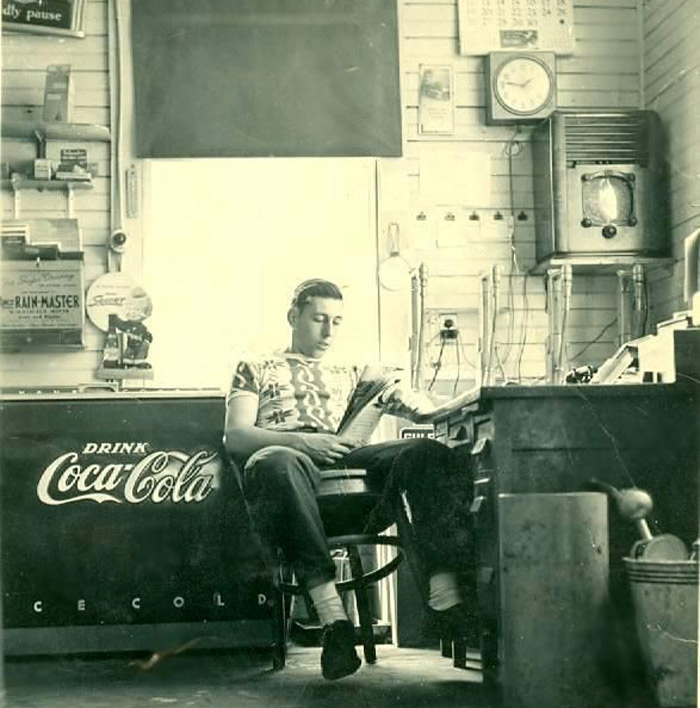

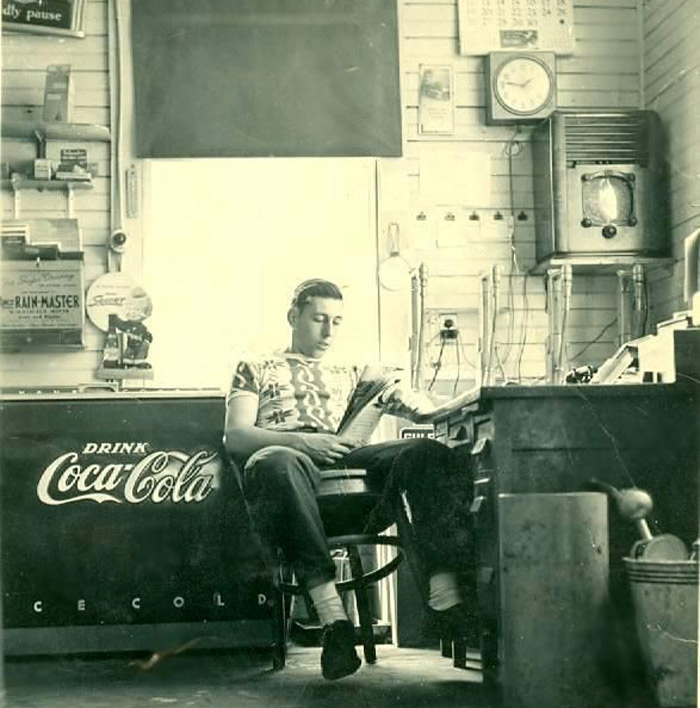

William Pinkerton, back in the day, hard at work at the dispatch desk at Bud Wood's taxi service in Rockland, Maine.

William Pinkerton, back in the day, hard at work at the dispatch desk at Bud Wood's taxi service in Rockland, Maine.

vintage

Maine

1950s

work

(h/t: Shorpy)

Rockland

Nov 18, 2012

In 1916, the Mountain Chief of the Piegan Blackfeet participated in a recording session with ethnologist Frances Densmore, who traveled the American West collecting Native music and reminiscences. The songs were recorded on wax cylinders and later pressed on vinyl.

In 1916, the Mountain Chief of the Piegan Blackfeet participated in a recording session with ethnologist Frances Densmore, who traveled the American West collecting Native music and reminiscences. The songs were recorded on wax cylinders and later pressed on vinyl.

In recent years, the Smithsonian has reissued much of the music, including a CD featuring a photo taken at the same time as this one. But the Blackfeet songs on the Smithsonian CD were all recorded no earlier than the 1930s. They are typical of Plains Indian songs, with elaborate vocalizations but very few words.

It is said that earlier Blackfeet songs, perhaps including the ones sung by this chief in 1916, had many more words and told long, complicated stories. Like so much of Native culture, it seems, the words are all gone now, and the singers have to try to sing without them.

vintage

music

Native American

Frances Densmore

1916

Plains Indian

Blackfeet

(Image credit: National Photo Company, via Shorpy)

Jul 12, 2013

All we know about this photo is that it was apparently taken in Calaveras County, California, about a hundred years ago. Looks like the boys in the band were family men.

All we know about this photo is that it was apparently taken in Calaveras County, California, about a hundred years ago. Looks like the boys in the band were family men.

Calaveras County is a famous place in the gold-mining country of the Sierra foothills, settled in a hurry by forty-niners and immortalized (sort of) by Mark Twain in his story about competitive frog-jumping.

Calaveras is Spanish for skulls.

vintage

California

band

1900s

Calaveras County

(Image credit: NDLXS via Shorpy)

Jan 10, 2018

Skiing behind a horse–the ancient Norwegian art of skijoring–in Northampton, England, 1908.

Skiing behind a horse–the ancient Norwegian art of skijoring–in Northampton, England, 1908.

vintage

horse

England

skijoring

1908

Northampton

(Image credit: Topical Press)

Jan 30, 2018

There's laundry in the yard here at the old Savage house, but only a few items; most of the clotheslines hold only empty clothespins. So we'll call it a Tuesday instead of a Monday.

There's laundry in the yard here at the old Savage house, but only a few items; most of the clotheslines hold only empty clothespins. So we'll call it a Tuesday instead of a Monday.

The house was built in 1861, only two years after discovery of the Comstock Lode, which set off a silver rush to Nevada, much like the gold rush to California a decade earlier. Administrative offices of the Savage Mining Company occupied the first floor; a succession of mine superintendents and their families lived above the offices, on the second and third floors.

The office and house were on D Street in the very young town of Virginia City, Nevada. The first Savage mine shaft was on B Street. Although the town was barely a year old in 1861, it already contained 42 saloons, 42 stores, 9 restaurants, 6 hotels, and a couple of thousand miners, many of whom had already spent years prospecting in California.

All the trees for miles around were already cut down, mostly for use as mine timbers.

The Savage mansion had 21 rooms and was probably the largest structure in town. The company provided a housekeeper for the superintendents in residence, and for many years the housekeepr was a Mrs. Monoghan, whose husband had died in one of the Savage mines.

In 1918, when Savage shut down its operations in Virginia City, after years in which mines thereabouts produced less and less good ore, the house, furnishings, and D Street property were deeded to Mrs. Monaghan. By the time this photographer happened by in 1940, the silver bonanza that built the house and the city had been over for a long, long time.

Recently, Virginia City is gentrifying, attracting tourists. The Savage Mansion is now completely restored and painted yellow. The building is still privately owned and serves as office space.

vintage

house

mining

work

1940

decay

Leonard Coates Savage

Comstock Lode

Virginia City, Nevada

(Image credit: Arthur Rothstein via Shorpy)

William Pinkerton, back in the day, hard at work at the dispatch desk at Bud Wood's taxi service in Rockland, Maine.

William Pinkerton, back in the day, hard at work at the dispatch desk at Bud Wood's taxi service in Rockland, Maine.