Empire State Spire

Feb 27, 2010

Looking southward down Manhattan from the top of 30 Rock, toward the Empire State Building and beyond. That's the Verrazano Narrows Bridge near the top of the photo, connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Feb 27, 2010

Looking southward down Manhattan from the top of 30 Rock, toward the Empire State Building and beyond. That's the Verrazano Narrows Bridge near the top of the photo, connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island.

Jul 14, 2010

During the godawful heat wave of July 1901, nobody in New York was in a good mood, and everybody was mad at the ice companies. The reason was that hot summer weather was associated with both increased demand for ice and reduced supply of well water with which to make ice at the big ice plants in Brooklyn and the Bronx. So the ice companies started using city water to supplement well water, and on the hottest days, they used so much municipal water that taps literally ran dry all over town. New Yorkers complained loudly to their elected officials, but the ice industry also had ways of "communicating" with politicians.

Giving away a little free ice--bring your own dishpan--was a public relations gesture on the part of the ice-makers. But note that a police presence was necessary at the ice lines.

The heat wave of July 1901, with temperatures near 100 degrees, killed thousands of people. The misery was compounded by the deaths of thousands of animals, including horses pulling ambulances and fire engines, who dropped dead in their traces while responding to emergencies. Sanitation crews fell far behind in removing carcasses from the streets. Anybody who could afford to get out of town got out of town.

Jan 27, 2011

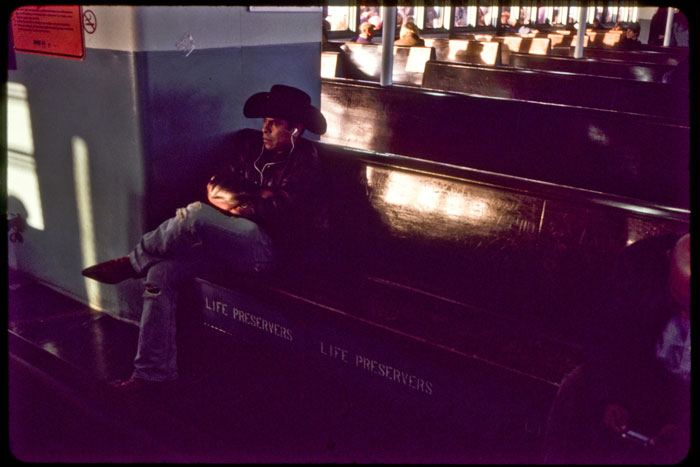

For most of the twentieth century, the fare for a ride on the Staten Island Ferry--a five-mile, twenty-five-minute trip between Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan Island and St. George Terminal at the northern tip of Staten Island--was a nickel. By the late 1960s, when I took my ferry ride, there really wasn't anything else on earth you could still buy for a nickel; even a coke had gone up to a dime.

For most of the twentieth century, the fare for a ride on the Staten Island Ferry--a five-mile, twenty-five-minute trip between Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan Island and St. George Terminal at the northern tip of Staten Island--was a nickel. By the late 1960s, when I took my ferry ride, there really wasn't anything else on earth you could still buy for a nickel; even a coke had gone up to a dime.

In the 1980s and 1990s the ticket price was raised a couple of times, till it cost a quarter. But then in 1997, for reasons I know nothing about, the fare was dropped altogether. It's a free ride now, and it operates twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Last year, people made twenty-one million trips on the ferry.

These people were taking their free ride late one night in December 2010.

Apr 25, 2011

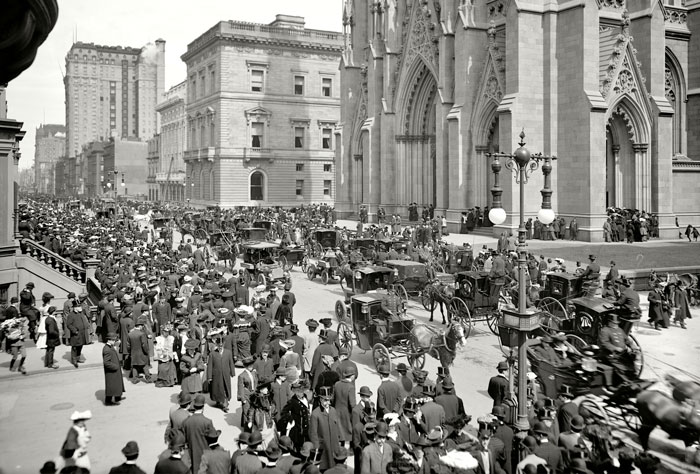

This was the scene on Fifth Avenue in New York City during the 1904 Easter Parade.

This was the scene on Fifth Avenue in New York City during the 1904 Easter Parade.

Easter Parades are different from all other parades: no floats, no marching bands. They began spontaneously in the 1870s, according to what I read on the intertubes, as people got dressed up in their finest and went downtown to promenade. Easter parades still existed in Washington when I was a little girl, I believe along Connecticut Avenue. I never actually saw one in person, but I did get new clothes, new white gloves, and sometimes even a new hat with a ribbon.

If you click on this picture and study the enlarged version, there are plenty of details for your delectation: a horseless carriage amidst the horsey kind, a boy delivering flowers, men with tophats amongst the men with bowler hats. . . .

Aug 15, 2011

I've done my due diligence on this; "Richie's photo is 100% legit," says Michele, the photographer's wife. No Photoshop.

I've done my due diligence on this; "Richie's photo is 100% legit," says Michele, the photographer's wife. No Photoshop.

The signs were posted at the corner of Madison Avenue and 81st Street in Manhattan, one block east of the Met. "Only in New York," observes Richie, the photographer–but I beg to differ. Traffic is all screwed up everywhere nowadays, as is politics and the economy, and if you know which way to go, don't even bother trying to tell me because I can't believe anybody any more.

Oct 6, 2011

As the sun sets over New Jersey, the Milano's Italian Sausage trucks begin their nightly rounds in Manhattan.

As the sun sets over New Jersey, the Milano's Italian Sausage trucks begin their nightly rounds in Manhattan.

New York City's new High Line Park repurposes an old elevated railroad track along the west side of lower Manhattan for strolling and people-watching high above the bustle of downtown streets. Trees and flowers grow out of the old track bed, blooming between the ties, while in the distance is the river, the skyscrapers, the restaurants and nightclubs, and, along this stretch of the route, the warehouses of the old meatpacking district.

Apr 2, 2012

Mike Adams's shot of dancers on the Coney Island boardwalk won a purchase award in the 2012 Double Exposure photographic exhibition in Tuscaloosa.

Mike Adams's shot of dancers on the Coney Island boardwalk won a purchase award in the 2012 Double Exposure photographic exhibition in Tuscaloosa.

Jun 15, 2012

Back in 1909, high school graduation day was something like prom night nowadays; it had become so expensive and extravagant that the editors of the New York Times were fussing about it.

Back in 1909, high school graduation day was something like prom night nowadays; it had become so expensive and extravagant that the editors of the New York Times were fussing about it.

A girl's graduation dress might cost $10--$280 today--or even more. At the city's Washington Irving High School, the dressmaking department came up with the idea of dollar dresses--fabric, trimming, thread, buttons, etc., all purchased for less than one dollar total--to be sewn by the graduate herself. Twenty-seven girls in the class of 1909 took up the challenge, and according to the New York Times, all twenty-seven dresses were indistinguishable from the expensive ones worn by their classmates on commencement day.

In 1905 my grandmother sewed herself a wedding dress that looked much like these dresses. Assuming that the fabric and notions must have cost her about dollar, she would have earned the money by selling a hundred glasses of seltzer at a penny apiece, and then washing all hundred glasses.

Sep 26, 2012

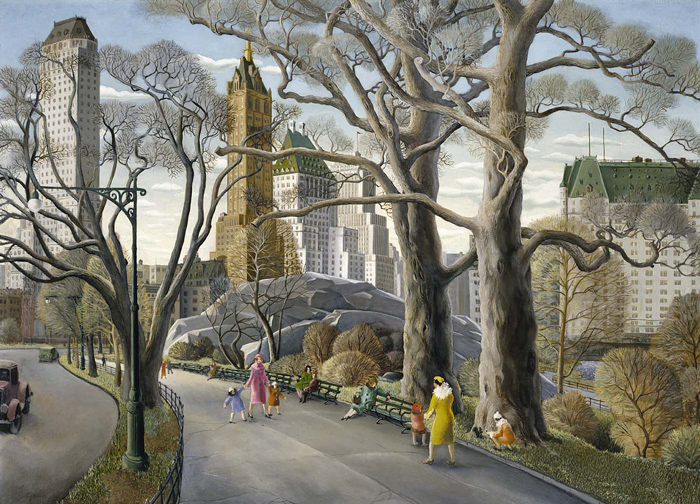

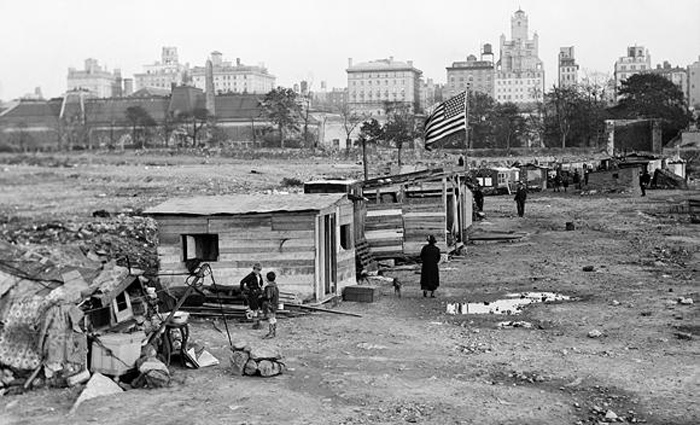

In 1934, Carl Gustaf Nelson painted life in New York's Central Park, above, the way life ought to be; in 1932 and 1933, photographers from the New York Daily News aimed their cameras at Central Park's Hooverville, below, revealing life that was not being lived the way people ought to live. Both images tell something of the story, in an upstairs-downstairs sort of way.

In 1934, Carl Gustaf Nelson painted life in New York's Central Park, above, the way life ought to be; in 1932 and 1933, photographers from the New York Daily News aimed their cameras at Central Park's Hooverville, below, revealing life that was not being lived the way people ought to live. Both images tell something of the story, in an upstairs-downstairs sort of way.

New York's homeless citizens began building shanties in Central Park's Sheep Meadow late in 1931, by which time half the factories in the city had been shut down by the Depression and literally millions of New Yorkers were desperate for food and shelter. In 1930 and 1931 homeless people tried to camp in Central Park, but they were repeatedly arrested for vagrancy; as the economic situation became more and more dire, however, policemen and judges became more sympathetic to the "bums," and official eyes were averted as this and many other Hoovervilles emerged. Some of the shacks were said to be solid brick and stone houses with tile roofs, built by unemployed bricklayers.

The residents of Central Park's Hooverville said they had built their homes along Depression Street. Many of the shanties had furniture and at least one had carpets, but there was no electricity or running water, no sanitary facilities at all. In 1933, the city condemned the dwellings, evicted the residents, and demolished the shantytown. The official justification was public health.

Thus, by 1934, when Nelson painted his picture, Central Park had been officially reclaimed for the sole use of well-dressed, well-to-do people like the ones in the painting, people with warm apartments to go home to and indoor plumbing. The people of Hooverville had moved on, and they would keep on moving on, scraping by, somehow, till a government stimulus program, aka World War II, finally brought full employment back to America.

Oct 5, 2012

New York City (2012), by Trey Ratliffe.

New York City (2012), by Trey Ratliffe.

Feb 24, 2013

One thing we have in abundance in America is abandoned railroad tracks. Many thousands of miles have been torn up and paved over with asphalt, repurposed for walking and biking through cities and suburbs. Many of these rails-to-trails are pleasant amenities, but few are interesting to look at or exciting to experience. Today, we turn our eyes to a few of those few.

New York City's High Line Park, which we last visited back in 2011, is a garden in the sky, snatched from the ruins of an industrial el line that once carried cattle and chickens to the slaughterhouses of lower Manhattan's Hudson riverfront. Both the industrial roots and the post-industrial decline are celebrated in the park: everywhere, the grit and grunge, patched brick walls and rusted steel fixtures, are lovingly preserved, with landscaping that looks a lot like weeds and old-looking new (creosote-free) train tracks in the flower beds. Amongst the weeds are miles of boardwalk for strolling and people-watching.

This photo was taken from the High Line's amphitheater, a performance space cantilevered out over Tenth Avenue, with glass walls that keep the sounds of the city at bay. Down below, about a block away on the left side of the street, you can glimpse the edge of a parking lot that is also being reimagined as performance space, for a senior project by a Parsons School of Design student, our own Amelia Stein. All of us Hole-in-the-Cloudsians are eager to follow the progress of this work by one of our own.

May 29, 2013

Last week, as we see here, our niece Amelia graduated from Parsons School of Design, winning her class's Golden Portfolio Award.

Last week, as we see here, our niece Amelia graduated from Parsons School of Design, winning her class's Golden Portfolio Award.

Two weeks ago, our niece Melissa donned cap and gown for her Master's in Nursing from Penn. And next week, it'll be another niece, Olivia, crossing the stage at Bloomington High School South in Indiana.

For our family, this commencement season is shaping up as one for the ages. And now as the nieces venture forth, may they all find fair winds and following seas.

Jul 18, 2013

This week in Brooklyn. Could be Philly.

This week in Brooklyn. Could be Philly.

Nov 21, 2014

Fulton Center, a new transit hub connecting four subway lines in lower Manhattan, opened to the public last week.

Fulton Center, a new transit hub connecting four subway lines in lower Manhattan, opened to the public last week.

Apr 11, 2015

One week ago, on a chilly but sunny New York afternoon, this espaliered pear tree in the Cloisters medieval garden was trying really, really hard to leaf out.

One week ago, on a chilly but sunny New York afternoon, this espaliered pear tree in the Cloisters medieval garden was trying really, really hard to leaf out.

Mar 12, 2016

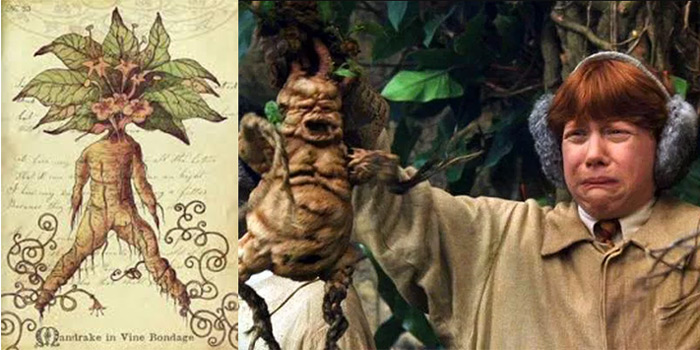

Mandrake, a plant of biblical, medieval, literary, medical, and comic book significance, blooms in April in New York City, in the garden of the Cloisters at the northern tip of Manhattan.

Mandrake, a plant of biblical, medieval, literary, medical, and comic book significance, blooms in April in New York City, in the garden of the Cloisters at the northern tip of Manhattan.

Mandrake flowers, shown here as buds just beginning to open, are pretty little bell-shaped blossoms, but they are traditionally of little interest. The leaves are heavy and heart-shaped and can grow huge over the course of a summer, but they too are mostly overlooked. With mandrake, a plant native to the Mediterranean region, it's all about the root.

Mandrake root is long and thick and often split into two legs, sometimes arguably resembling the human form. It's also powerfully sleep-inducing when ground and soaked; it was used as an anesthetic in antiquity and into the Middle Ages. In the bible, and perhaps also in the poetry of John Donne, extract of mandrake root cured infertility. In folklore all over Europe, a human-shaped mandrake root in your pocket offered protection even if the church was not on your side; Joan of Arc was charged with "habitually" carrying root of mandrake.

Mandrake was said to spring up in ground drenched with blood or semen from a man being hanged. If you pulled the plant up out of the ground, as Shakespeare warned us, its man-root would scream, and you could die from hearing the scream. There was a report as late as the ninteenth century of a British gardener falling down the stairs and dying after accidentally pulling up a volunteer mandrake.

(In Harry Potter, of course, young witches and wizards wore protection.)

In 1934, "Mandrake the Magician" emerged as the world's first modern costumed superhero, in a newpaper comic strip that ran continuously until 2013. The hero Mandrake's ability to instantly hypnotize bad guys may have been, pardon the expression, rooted in the medicinal tradition of the mandrake plant.

Jan 12, 2017

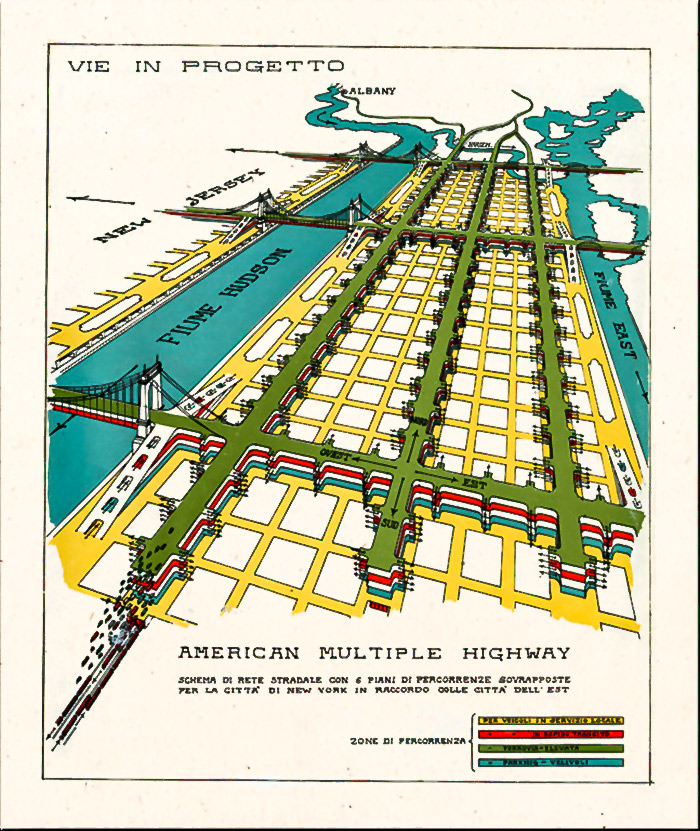

When Italian architect Renzo Picasso visited New York City in the 1920s, he correctly identified traffic and parking as bad problems that would become much worse over time.

When Italian architect Renzo Picasso visited New York City in the 1920s, he correctly identified traffic and parking as bad problems that would become much worse over time.

There was no more land in Manhattan to pave over, so Picasso (no relation to that Spanish guy) took his cue from the skyscrapers and proposed to build the streets up vertically. He envisioned at least four transportation levels: trains up on top, express automobile traffic on the layer second to top, parking on the level below that, and local traffic on the bottom.

Picasso's vision for this American Multiple Highway, which he presented in 1929, was one of many utopian projects he sketched out for cities in the United States and Europe. None of them was ever built.

Jan 28, 2017

On the G-train, in Brooklyn.

On the G-train, in Brooklyn.