Hole in the Clouds

Jul 31, 2011

Last week in Atlantic City, it was too hot to stroll the boardwalk, though we did that anyway, and really too hot to sit out on the beach. I guess we were supposed to linger in the casinos, but it would take a lot more than summer heat to make that seem like fun to me. There were other entertainment options, of course, including this watershow in an air conditioned mall built on a pier out over the sea. The show ran for a few minutes every hour, to the accompaniment of patriotic music and digital covers of old bluegrass fiddle tunes.

Last week in Atlantic City, it was too hot to stroll the boardwalk, though we did that anyway, and really too hot to sit out on the beach. I guess we were supposed to linger in the casinos, but it would take a lot more than summer heat to make that seem like fun to me. There were other entertainment options, of course, including this watershow in an air conditioned mall built on a pier out over the sea. The show ran for a few minutes every hour, to the accompaniment of patriotic music and digital covers of old bluegrass fiddle tunes.

The occasion was a gathering of Norman and his mother and both his brothers and their sister, together for the first time in a couple of years. No kids, no pets, much discussion of "the Grandpa Abe gene," which is how Norm's brothers and sister explain their interest in rolling the dice for hours and hours while they win a little money and then lose a little and then win some back and keep on betting.

Grandpa Abe, their father's father, who operated an elevator for a living, was apparently a pretty serious gambler as a young man. Grandma Sadie refused to marry him, I'm told, till he swore off the habit–and he stuck by his pledge, more or less, limiting himself to playing the horses at off-track betting establishments.

It seems that the Grandpa Abe gene skipped over Norman but expresses itself in all his siblings at the craps table. They had a lot of fun gambling, and even the non-gamblers among us enjoyed the company and look forward to the next visit.

The water was fine. As for the rest of Atlantic City, it is what it is.

New Jersey

Atlantic City

water

fountain

mall

Aug 3, 2011

In hopes of maintaining secure communication with its ships and submarines at sea, no matter what, the U.S. Navy maintains arrays of thousand-foot-high Very Low Frequency transmitter towers at three locations around the world. This is the Navy's Cutler array, the largest and most powerful radio installation in the world, with 26 towers located on a peninsula at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in downeast Maine, near Machias.

In hopes of maintaining secure communication with its ships and submarines at sea, no matter what, the U.S. Navy maintains arrays of thousand-foot-high Very Low Frequency transmitter towers at three locations around the world. This is the Navy's Cutler array, the largest and most powerful radio installation in the world, with 26 towers located on a peninsula at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in downeast Maine, near Machias.

Cutler, constructed in 1961, is 100 percent Cold War technology: no GPS, no internet, no cellphone network. The biggest towers in the world were built here because this station services vessels in the Arctic Ocean as well as the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and naturally occuring electromagnetic pulses in the Arctic–the Aurora Borealis–can interfere with all but the most powerful radio signals.

The transmitters here run on power generated on-site and distributed to the towers by underground wiring. Underground wires also extend far offshore under the ocean, to maximize communication with submarines. There are no naval personnel working in Cutler; a civilian crew maintains the site, which sends out encrypted signals generated at a base in Norfolk, Virginia.

Although this shaky picture, which was taken with a handheld camera on a dark and cloudy night, suggests a somewhat haphazard string of towers, they are actually arranged in two identical clusters, which can operate separately or together. Each cluster can be shut down as necessary for maintenance. There's a problem, however, in the part of the installation around the power plant, where the two clusters are so close to one another that the electromagnetic field can be hazardous to humans, even when one of the clusters is shut down.

This area of the installation is called the Bowtie. People doing maintenance try to work as little as possible in the Bowtie, because even if they are working on towers that have been shut down they may still be exposed to dangerous electrical radiation from nearby still-active towers.

Because the Navy requires that at least one of the Cutler clusters must be functioning at all times, the towers in the Bowtie area of the installation have seen little maintenance over the years. In particular, they have never been painted, and they are now fifty years old. The civilians onsite requested a four-month shutdown of the entire array to complete the painting, but the Navy said no.

I predict one of two probable resolutions: either they'll run out of money for the paint job and just let the salt and snow do their thing on the thousand-foot towers, or else they'll redefine the safety standard for electromagnetic radiation so that working in the Bowtie magically becomes safe.

Can you get cellphone service on submarines?

Maine

Navy

night

seascape

water

submarines

Atlantic Ocean

towers

Cutler

Jul 18, 2013

This week in Brooklyn. Could be Philly.

This week in Brooklyn. Could be Philly.

children

summer

streetscape

New York City

Brooklyn

water

(h/t: JJ Stein)

(Image credit: Brendan McDermid for Reuters)

Jun 23, 2014

I wanna play too.

I wanna play too.

kids

summer

water

waterfall

frisbee

play

(Image credit: Danyel Suryana via Fujirumors)

Feb 10, 2015

It was a nice flat little rock that hopped across a nice icy little river, at the foot of a nice little rocky mountain in the eastern panhandle of West Virginia.

It was a nice flat little rock that hopped across a nice icy little river, at the foot of a nice little rocky mountain in the eastern panhandle of West Virginia.

To see how it's done, see here.

West Virginia

water

reflection

Cacapon River

ripples

(Image credit: Fuji T)

Feb 21, 2016

One of the hangers-on at a marina near Everett, Washington, pokes his head up from the waters of Puget Sound in hopes that the incoming salmon-fishing charter boats had a good day.

One of the hangers-on at a marina near Everett, Washington, pokes his head up from the waters of Puget Sound in hopes that the incoming salmon-fishing charter boats had a good day.

Washington

water

fishing

seal

Everett

salmon

(Image credit: Fuji T)

May 18, 2016

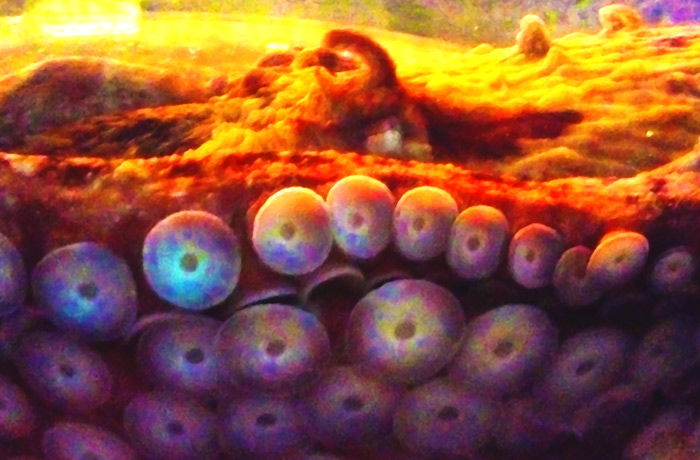

A Giant Pacific Octopus at the Seattle Aquarium posed recently for my mother to take a picture with her phone.

A Giant Pacific Octopus at the Seattle Aquarium posed recently for my mother to take a picture with her phone.

These varmints can weigh up to 150 pounds and spread their arms to wrap up a house. The 200 suckers on each arm are used to trap and hold prey, especially crabs and other crustaceans, which the octopus may paralyze with toxic saliva before tearing apart with its parrot-like beak.

To ambush its prey, the octopus hides amongst the rocks and seaweed, blending in with its surroundings by changing color at will. It can even change its texture, mimicking its surroundings by raising lumps or knobs of muscle.

The entire animal is so squishy and transformable that only its beaklike mouth sets a limit to its shape-shifting. If it wants to, a Giant Pacific Octopus can squeeze itself through a hole the size of a lemon.

water

Seattle

underwater

aquarium

octopus

(Image credit: S. Horowitz)

Jan 7, 2017

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

He grew up hating school, though in about 1930 he did manage to stick out one semester at the University of Toledo, where he said he learned nothing interesting or useful. Over the succeeding 80 or so years, he taught himself whatever he felt like learning, whenever he felt like learning it.

He especially liked new technology, the latest thing. When he was a little boy, the latest thing was a Kodak Brownie camera, which cost one dollar; Olson taught himself to shoot pictures, and he set up a darkroom to develop and print them.

By 1930, the new thing was radio. Olson taught himself to fix radios, to build them, to build better ones. He started a one-man repair shop. By 1963, when he retired on his fiftieth birthday, his little shop had become Olson Electronics, a nationwide chain of 95 stores plus a mail order business, selling parts for radios and every other kind of electronic gizmo. Olson sold his company to a corporation that turned it into Radio Shack.

Long after he retired, he continued fiddling with and teaching himself all about new technological developments. He'd been a photographer all along, publishing travel photos and many others, but at the age of 79 he decided he had to make the switch to digital cameras and computerized photo processing. He taught himself Photoshop when he was in his nineties.

Everything came together for Olson at the age of 97. By then, he'd been retired for almost half a lifetime. He'd outlived his wife of 71 years and settled into an apartment in a senior-living community in Arizona. He'd finally stopped traveling, after visiting 135 different countries; airports were just too unpleasant, he said.

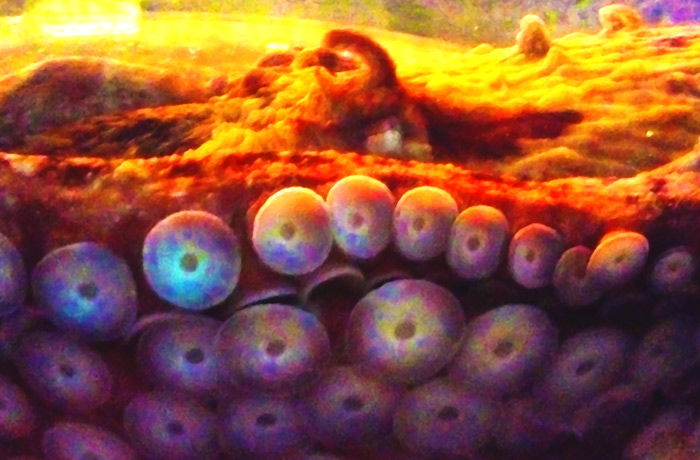

But he was still up for a challenge. And that was when he spotted an article in a technical photography journal about shooting photos of the collision of two drops of water. "I could do that," Olson thought to himself. "In fact, if I color the water, I can make it really interesting."

He turned his kitchen into a lab and got to work. After two years of experimentation, he finally had a setup that reliably produced nice pictures of drops of water banging into each other, some of them really interesting. In this context, "some of them" means that he considered about 1 picture in 500 worth keeping.

When a drop of water falls into a pan of water, it actually bounces a little, about two inches. If a second drop is released so it falls onto the first drop just at the top of the bounce, you might have a good picture. Olson experimented with timing, with lighting, with the size of the drops, with colors, with milk and other additives to change viscosity.

"If you think this is complex, it is," he told the editors at Smithsonian magazine. "If it is almost impossible, I like it a lot."

His photos have been exhibited all over the world, including a one-man show in New York's Grand Central Station. When he turned 100, the University of Akron awarded him an honorary doctorate.

Basically, Olson spent the final years of his life in a darkened kitchen–not all that different from the photographic darkrooms of his early years–fiddling with a drippy faucet kind of thing. By all accounts, it made him really, really happy.

photography

water

Irving Olson

experimentation

Radio Shack

centenarian

Olson Electronics

(Image credits: Irving Olson)

Last week in Atlantic City, it was too hot to stroll the boardwalk, though we did that anyway, and really too hot to sit out on the beach. I guess we were supposed to linger in the casinos, but it would take a lot more than summer heat to make that seem like fun to me. There were other entertainment options, of course, including this watershow in an air conditioned mall built on a pier out over the sea. The show ran for a few minutes every hour, to the accompaniment of patriotic music and digital covers of old bluegrass fiddle tunes.

Last week in Atlantic City, it was too hot to stroll the boardwalk, though we did that anyway, and really too hot to sit out on the beach. I guess we were supposed to linger in the casinos, but it would take a lot more than summer heat to make that seem like fun to me. There were other entertainment options, of course, including this watershow in an air conditioned mall built on a pier out over the sea. The show ran for a few minutes every hour, to the accompaniment of patriotic music and digital covers of old bluegrass fiddle tunes.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.