Hole in the Clouds

Jan 1, 2018

New year or no new year, new Mondays are always in our face.

New year or no new year, new Mondays are always in our face.

From 1995 to 2002, Finnish photographer Tiina Itkonen chronicled life in an Inughuit village in the highlands of extreme northern Greenland. The Inughuit are our planet's northernmost residents.

Another photo from Itkonen's Inughuit Portraits series shows a smaller pair of those polar bear trousers on the legs of a young boy named Masaitsiaq. Low on the wall behind Masaitsiaq are six sharp knives mounted on a magnet. Inughuit babies and toddlers must develop caution and common sense at a much earlier age than the children we know.

Alaska

clothesline

Monday

(Imag credit: Tiina Itkonen)

Jan 2, 2018

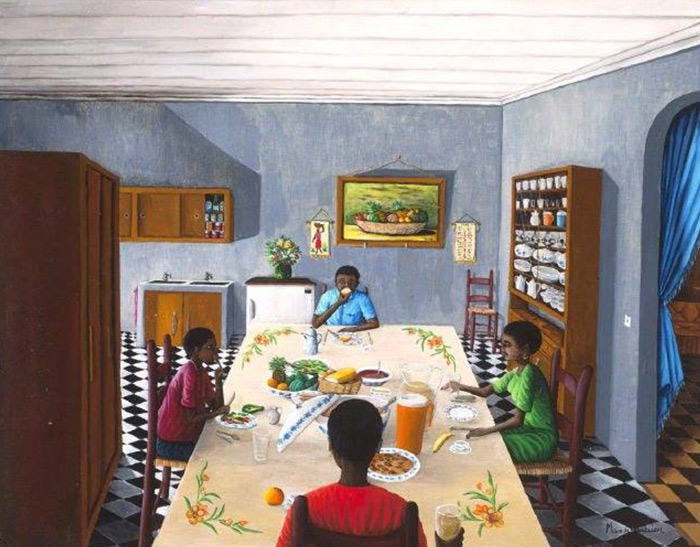

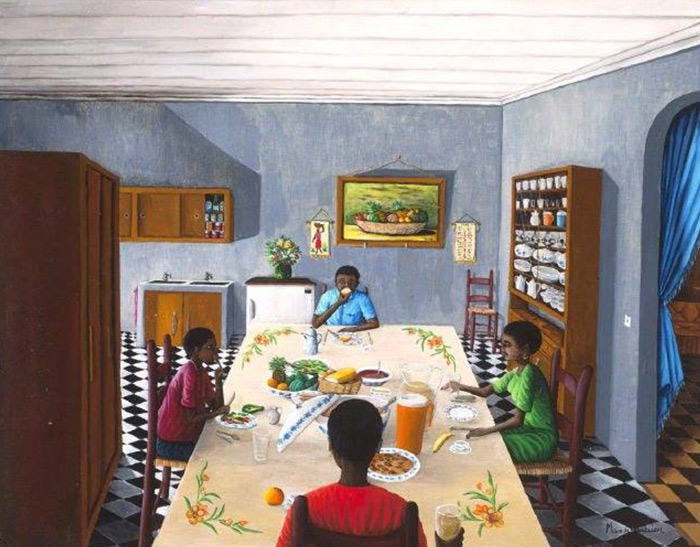

"Bourgeois Dining" (1982), by Haitian painter Max Gerbier.

"Bourgeois Dining" (1982), by Haitian painter Max Gerbier.

painting

food

table

eating

Haiti

(Art by Max Gerbier)

Jan 3, 2018

View from above of the container port at Portsmouth, Virginia.

View from above of the container port at Portsmouth, Virginia.

aerial view

cranes

Virginia

containers

Portsmouth

pattern

(Image credit: Alex MacLean)

Jan 4, 2018

The woman in black is standing at the Summit Avenue streetcar stop, looking back across Brighton Street in Boston in 1938.

The woman in black is standing at the Summit Avenue streetcar stop, looking back across Brighton Street in Boston in 1938.

The streetcar platform was taken down in 2004, but all the buildings in this scene, and even the billboard around the bend, are still there today.

What was she doing there? What was she thinking? Did she know somebody was taking her picture?

Boston

streetscape

1938

(photographer unknown, via Shorpy)

Jan 5, 2018

Mabel sits and yawns on a sunny ridge near Mount Rainier last week, showing off her Happy New Year hat.

Mabel sits and yawns on a sunny ridge near Mount Rainier last week, showing off her Happy New Year hat.

landscape

dog

winter

snow

mountain

Mount Rainier

Mabel

(Image credit: Harrison Stein)

Jan 6, 2018

In the wintry weather currently gripping eastern North America, icy mounds of frozen spray, known as sugarloaves, are growing huge atop frozen rivers below not-quite-fully-frozen waterfalls. There's a sugarloaf at the base of Niagara Falls this year, and also one at Montmorency Falls near Québec City; the falls at Montmorency are some 98 feet higher than Niagara and are located almost a thousand kilometers to the northeast, in a climate zone where every winter is plenty cold enough to make a sugarloaf.

In the wintry weather currently gripping eastern North America, icy mounds of frozen spray, known as sugarloaves, are growing huge atop frozen rivers below not-quite-fully-frozen waterfalls. There's a sugarloaf at the base of Niagara Falls this year, and also one at Montmorency Falls near Québec City; the falls at Montmorency are some 98 feet higher than Niagara and are located almost a thousand kilometers to the northeast, in a climate zone where every winter is plenty cold enough to make a sugarloaf.

The painting shown above, The Ice Cone, by Robert Clow Todd, shows Montmorency Falls and its sugarloaf in the winter of 1845. The place looked pretty much the same when we visited, in the winter of 2004, minus the horses, of course.

Tall, cone-shaped things with slightly blunted tips are often called sugarloaves, especially if they are ski resorts or a mountain in Rio de Janeiro with a statue on top. That's because real, old-school sugarloaves–actual hard, solid loaves of refined sugar–were produced in molds shaped like that. Up until the end of the nineteenth century, when manufacturing processes emerged to refine sugar into a granulated product, people who could afford to buy white sugar–meaning rich people–bought it by the loaf, which might weigh as much as 30 or 35 pounds. They chipped off pieces as needed, using heavy, sharp-edged pliers known as sugar nips.

The sugarloaves pictured below are on display in the Sugar Museum in Berlin.

landscape

Canada

winter

snow

ice

Berlin

waterfall

Quebec

sugar

Montmorency Falls

Sugar Museum

(Art by Robert Clow Todd)

Jan 7, 2018

It was a thousand and one years ago yesterday that the Viking Cnut (aka Knut, Knud, or Canute) was crowned King of All England.

It was a thousand and one years ago yesterday that the Viking Cnut (aka Knut, Knud, or Canute) was crowned King of All England.

Cnut was a wise and good king, or so they say, but he is best remembered for something he didn't do. Briefly: it was told of him that he had his throne placed in the surf at the seaside, where he held court in his robes and crown with full royal regalia. He ordered the tide to go back out, but the tide didn't obey. "See that?" said Cnut, more or less. "I'm not the one who really runs things around here."

It never happened; the story is a bit like the legend of George Washington chopping down that cherry tree, in that it first appeared long after Cnut's death in the moralistic writings of a clergyman.

But what's the moral of the non-event? The usual interpretation, even to this day, is that Cnut was an idiot with delusions of grandeur, who badly needed a reality check with respect to the powers that be.

But the intended lesson, according to Henry, Archdeacon of Huntingdon, who first wrote the apocryphal story as a poem in the twelfth century, was that King Cnut knew from the start that no edict of his could turn back the tide. He was a wise and good king. His courtiers, on the other hand, were brown-nosing fools who expected way too much from him–in other words, they were getting on his nerves. He staged a little demonstration to remind them that even the King of All England was a mere mortal who had his limits.

Which brings us to tomorrow, January 8, when a pack of hounds from the realm of Georgia will attempt to turn back the Crimson Tide of Alabama in a sporting contest established to determine the collegiate football champion of all America.

Cnut couldn't do it. Can the Dawgs of Georgia? We'll find out, won't we. Roll Tide.

football

Crimson Tide

England

King Cnut

Henry of Huntingdon

Vikings

apocryphal stories

stopping the tide

Jan 8, 2018

Our son Joe and his Cuban sweetheart Yusleidy Perez Zanetti are getting married next month. They are planning a wedding in Havana, but meanwhile, they've got clothes to dry out on the balcony.

Our son Joe and his Cuban sweetheart Yusleidy Perez Zanetti are getting married next month. They are planning a wedding in Havana, but meanwhile, they've got clothes to dry out on the balcony.

wedding

(Image credit: Joe Stein

Jan 9, 2018

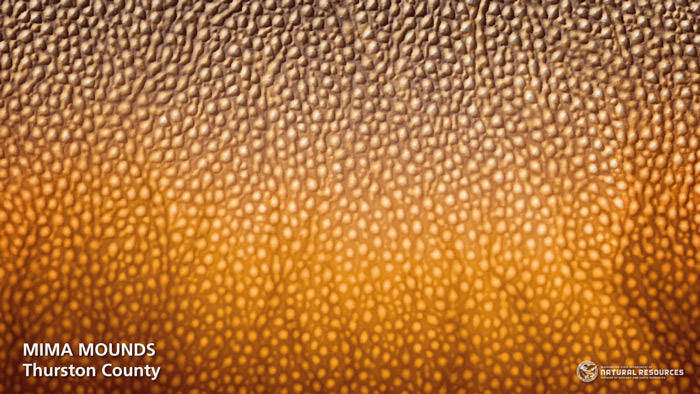

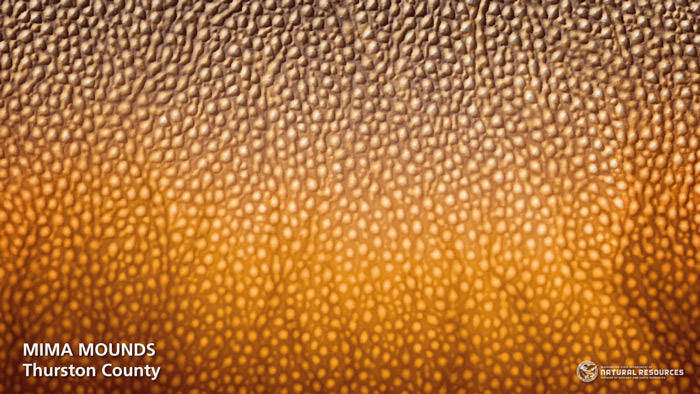

Near the southern extreme of Puget Sound, around Olympia, Washington, are hundreds of acres of bumpy grassland, the Mima Mounds. The picture above–aerial imagery produced by a radar-sensitive LIDAR camera–shows what the Mima landscape looks like without all the grass and shrubs that soften the lumpy appearance. the picture below shows what it looks like to the human eye.

Near the southern extreme of Puget Sound, around Olympia, Washington, are hundreds of acres of bumpy grassland, the Mima Mounds. The picture above–aerial imagery produced by a radar-sensitive LIDAR camera–shows what the Mima landscape looks like without all the grass and shrubs that soften the lumpy appearance. the picture below shows what it looks like to the human eye.

LIDAR is a radar technology used to determine elevation, and it works even when the actual ground level is hidden underneath vegetation or buildings; when a plane flies over an area of interest and sends radar signals straight down to earth, the signals will bounce back differently depending on what they hit. Of course you need a computer to sort it all out, but they've got computers.

What the computers haven't been able to figure out is what caused these mounds, which are pretty much all very round and low and flat; in the Mima prairie, most of the mounds are about 3 feet high and 30 feet across. They are gravelly dirt, just like the spaces between them.

Similar-looking mounds are found in dozens of other places, and no single mechanism has been identified that might account for them everywhere. Among the possible processes that have been researched in the Mina region: earthquakes shaking the soil, clay minerals shrinking and swelling in the soil, windblown dunes forming around vegetation, and–our favorite–burrowing by pocket grophers, perhaps with help from termites and ants.

Scientific consensus on this matter has yet to emerge.

landscape

soil

LIDAR

prairie

prairie dogs

Mima Mounds

(Image credits: above, Washington State Department of Natural Resources; below, Jerrye and Roy Klotz)

Jan 10, 2018

Skiing behind a horse–the ancient Norwegian art of skijoring–in Northampton, England, 1908.

Skiing behind a horse–the ancient Norwegian art of skijoring–in Northampton, England, 1908.

vintage

horse

England

skijoring

1908

Northampton

(Image credit: Topical Press)

Jan 11, 2018

The Bainbridge Island ferry and the Olympic Mountains at sunset, as seen across Elliott Bay from the bar at Pier 67 near downtown Seattle.

The Bainbridge Island ferry and the Olympic Mountains at sunset, as seen across Elliott Bay from the bar at Pier 67 near downtown Seattle.

landscape

mountains

sunset

Puget Sound

Seattle

ferry

(Image credit: Fuji T)

Jan 12, 2018

It's dark, chilly midwinter here in the Pacific Northwest, but the supermarket shelves are piled high with sweet summer raspberries and blueberries and blackberries. All those berries can't be coming from around here–blackberries are notorious weeds hereabouts and other berries grow readily, but the plants are dormant in the winter and yield fruit only in the summer.

It's dark, chilly midwinter here in the Pacific Northwest, but the supermarket shelves are piled high with sweet summer raspberries and blueberries and blackberries. All those berries can't be coming from around here–blackberries are notorious weeds hereabouts and other berries grow readily, but the plants are dormant in the winter and yield fruit only in the summer.

Parts of Chile are climatically similar, though of course with the seasons reversed, and so Chilean berry-growers started loading their fruit on big cargo planes and flying it all the way up here in the wintertime, to be sold at very high prices reflecting the cost of air transport.

Nowadays, however, Chilean berries are all used for juice; the air-shipping premium was just too costly to make them competitive in the fresh-berry market. The huge North American market for fresh berries–which is booming at the moment, thanks to crazes for antioxidants and smoothies–depends on locally grown fruit in the summertime and then, for literally every other month of the year, on berries grown in greenhouse-like plastic tunnels high in the mountains of the Mexican state of Jalisco.

If chilled immediately, fresh berries can have a shelf life of more than a month, which is plenty of time for refrigerated trucks to carry them from their greenhouse tunnels–tuneles–in central Mexico to virtually any grocery store in the U.S.

The high-altitude berry farms, a mile or more above sea level and cooled a bit by Pacific breezes, don't get as searingly hot in the summertime as the rest of Mexico. The semi-shade in the plastic tunnels further blunts the subtropical sun and also slows evaporation, saving water.

But even with all these adaptations, berry bushes and canes in Mexico don't behave the same way they do in, say, Oregon or New Jersey. In Jalisco, the plants rest in the summertime and produce fruit in cooler months–which is just when the North American market has particular call for them.

The tunnels do yield less fruit per acre, but Mexican growers are okay with that; their overall costs are still low. In fact, in the last ten years they have converted so much land to blueberries and raspberries and blackberries that Mexican fresh-berry-production has become a billion-dollar industry.

Mexicans, however, still don't really care for the taste.

Mexico

fruit

agriculture

Jan 13, 2018

In 1907, Ernest Shackleton led his first expedition aimed at reaching the South Pole. He'd already spent years in Antarctica, serving under Robert Scott, failing to reach the Pole but learning much about survival and leadership. Shackleton's 1907 trip would make it closer to the Pole by far than earlier explorers, though he and his men still fell short by 87 miles.

In 1907, Ernest Shackleton led his first expedition aimed at reaching the South Pole. He'd already spent years in Antarctica, serving under Robert Scott, failing to reach the Pole but learning much about survival and leadership. Shackleton's 1907 trip would make it closer to the Pole by far than earlier explorers, though he and his men still fell short by 87 miles.

They first landed in Antarctica at a place called Cape Royd on McMurdo Sound, where Shackleton oversaw the building of his hut for wintering over in Antarctica. He and his men huddled there through the winter of 1908, and when they left that spring to attempt their sprint to the Pole, the hut was equipped with food and fuel to last 15 men for one year.

They left a note with details about provisions and the coal store and then locked the door and nailed the key to the door.

They never returned to the hut, though they did make it back safely to England in 1909, where Shackleton immediately began planning his next trip to the South Pole.

Almost a century later, in 2006, the hut was dug out of the ice and snow and reopened. Much of the food was described as "perfectly preserved," though some meat was said to be quite rancid. Several cases of McKinlay & Co. scotch whisky were retrieved from the cellar and found to be delicious; based on a chemical analysis of this whisky, the distillery is again producing the old single-malt scotch.

The hut has now been restored through the World Monuments Fund, and the land surrounding it has been designated an Antarctic Specially Protected Area.

Shackleton did succeed in raising money for another expedition, which set sail on the Endurance in 1914 but never reached the Antarctic mainland; he Endurance was crushed by ice near the coast, initiating years of fear and suffering, out on the sea ice. Shackleton's renown as a leader dates from this disastrous voyage, when he was able to sustain morale and eventually get the men to safety 700 miles away at a whaling station in the South Georgia Islands. They made it back to England in 1917.

His fully provisioned little hut, meanwhile, complete with a coal-burning stove and crates of scotch, sat on the opposite edge of the Antarctic continent, closer to New Zealand than to South America. It might as well have been on the moon.

Antarctica

Ernest Shackleton

hut

exploration

deep freeze

(Image credit: Trey Ratcliff via Stuck in Customs)

Jan 14, 2018

Our granddaughter Robin is in preschool now, one morning a week. This week, she learned how to bake a ball in the oven.

Our granddaughter Robin is in preschool now, one morning a week. This week, she learned how to bake a ball in the oven.

school

ball

Robin

lessons

housekeeping corner

(Image credit: Bonnie Strelitz)

Jan 15, 2018

Money laundering is one of those things, we're told, that's happening all over and all the time. Some countries make it easy for, say, drug traffickers to disguise the source of their riches, either through an opaque banking system, as in Switzerland, a financial sector rotten with greasy palms, as in the Cayman Islands, or an overheated real estate market, as in the business model associated with Donald Trump. Or so we're told.

Latin American gangsters, Russian mobsters, all sorts of bad guys from all over can create shell corporations in Delaware that invest in, say, condos in Trump properties, in Manhattan, Panama, Azerbaijan, wherever. If a real estate developer undertakes careful investigation ((extreme vetting?), then fake corporations associated with ill-gotten gains may be blocked from such purchases. But the kind of developer that doesn't really care . . .

"It's possible," said Trump last summer, in a conversation about how he really, really didn't want Mueller to look into his finances. "I mean, I sell a lot of condo units, and somebody from Russia buys a condo, who knows?"

money laundering

Jan 16, 2018

Posing for an action shot in a softball game at a Y camp in Plano, Illinois, 1930.

Posing for an action shot in a softball game at a Y camp in Plano, Illinois, 1930.

sports

summer

1930

softball

Plano, Illinois

(Image credit: Wittman Bros. via Shorpy)

Jan 17, 2018

Fog swallows the tips of new skyscrapers around an old tree in the Pudong Financial District of Shanghai.

Fog swallows the tips of new skyscrapers around an old tree in the Pudong Financial District of Shanghai.

Shanghai

China

tree

skyline

skyscrapers

fog

Pudong Financiall District

(Image credit: Aly Song for Reuters)

Jan 18, 2018

Pushing a baby stroller at sunset, across a frozen lake near Lahti, Finland.

Pushing a baby stroller at sunset, across a frozen lake near Lahti, Finland.

sunset

baby

winter

ice

lake

Lahti, Finland

stroller

(Image credit: Kai Pfaffenbach for Reuters)

Jan 29, 2018

Women washing clothes circa 1900 in Alatri, Italy, 100 kilometers southeast of Rome.

Women washing clothes circa 1900 in Alatri, Italy, 100 kilometers southeast of Rome.

laundry

Italy

1900

women

Alatri

Jan 30, 2018

There's laundry in the yard here at the old Savage house, but only a few items; most of the clotheslines hold only empty clothespins. So we'll call it a Tuesday instead of a Monday.

There's laundry in the yard here at the old Savage house, but only a few items; most of the clotheslines hold only empty clothespins. So we'll call it a Tuesday instead of a Monday.

The house was built in 1861, only two years after discovery of the Comstock Lode, which set off a silver rush to Nevada, much like the gold rush to California a decade earlier. Administrative offices of the Savage Mining Company occupied the first floor; a succession of mine superintendents and their families lived above the offices, on the second and third floors.

The office and house were on D Street in the very young town of Virginia City, Nevada. The first Savage mine shaft was on B Street. Although the town was barely a year old in 1861, it already contained 42 saloons, 42 stores, 9 restaurants, 6 hotels, and a couple of thousand miners, many of whom had already spent years prospecting in California.

All the trees for miles around were already cut down, mostly for use as mine timbers.

The Savage mansion had 21 rooms and was probably the largest structure in town. The company provided a housekeeper for the superintendents in residence, and for many years the housekeepr was a Mrs. Monoghan, whose husband had died in one of the Savage mines.

In 1918, when Savage shut down its operations in Virginia City, after years in which mines thereabouts produced less and less good ore, the house, furnishings, and D Street property were deeded to Mrs. Monaghan. By the time this photographer happened by in 1940, the silver bonanza that built the house and the city had been over for a long, long time.

Recently, Virginia City is gentrifying, attracting tourists. The Savage Mansion is now completely restored and painted yellow. The building is still privately owned and serves as office space.

vintage

house

mining

work

1940

decay

Leonard Coates Savage

Comstock Lode

Virginia City, Nevada

(Image credit: Arthur Rothstein via Shorpy)

New year or no new year, new Mondays are always in our face.

New year or no new year, new Mondays are always in our face.

It was a thousand and one years ago yesterday that the Viking Cnut (aka Knut, Knud, or Canute) was crowned King of All England.

It was a thousand and one years ago yesterday that the Viking Cnut (aka Knut, Knud, or Canute) was crowned King of All England.  Our son Joe and his Cuban sweetheart Yusleidy Perez Zanetti are getting married next month. They are planning a wedding in Havana, but meanwhile, they've got clothes to dry out on the balcony.

Our son Joe and his Cuban sweetheart Yusleidy Perez Zanetti are getting married next month. They are planning a wedding in Havana, but meanwhile, they've got clothes to dry out on the balcony.

It's dark, chilly midwinter here in the Pacific Northwest, but the supermarket shelves are piled high with sweet summer raspberries and blueberries and blackberries. All those berries can't be coming from around here–blackberries are notorious weeds hereabouts and other berries grow readily, but the plants are dormant in the winter and yield fruit only in the summer.

It's dark, chilly midwinter here in the Pacific Northwest, but the supermarket shelves are piled high with sweet summer raspberries and blueberries and blackberries. All those berries can't be coming from around here–blackberries are notorious weeds hereabouts and other berries grow readily, but the plants are dormant in the winter and yield fruit only in the summer.

Fog swallows the tips of new skyscrapers around an old tree in the Pudong Financial District of Shanghai.

Fog swallows the tips of new skyscrapers around an old tree in the Pudong Financial District of Shanghai. Pushing a baby stroller at sunset, across a frozen lake near Lahti, Finland.

Pushing a baby stroller at sunset, across a frozen lake near Lahti, Finland. Women washing clothes circa 1900 in Alatri, Italy, 100 kilometers southeast of Rome.

Women washing clothes circa 1900 in Alatri, Italy, 100 kilometers southeast of Rome.