Hole in the Clouds

May 8, 2011

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

We met trekkers from the Netherlands, Australia, Israel, France, Japan, Ireland, Germany, and probably some other countries I've forgotten. The group in the foreground here was from China.

Very few came from the United States. Americans generally don't have the vacation time or the "hillwalking" tradition shared by the Europeans. However, patterns of tourism are changing; in the resort city of Pokhara, which we visited after our trek, we met a tour group of senior citizens from New Jersey.

landscape

Nepal

Himalayas

Poon Hill

trekkers

photography

Aug 18, 2011

Natsumi Hayashi calls herself the Yowayowa Camera Woman, yowayowa being a Japanese word for weak or feeble. "Since I'm yowayowa," she says, "it's really heavy to carry SLR cameras around."

She lives in Tokyo with two cats and is devoted to her art: photography, "mainly levitating self-portraits." Levitating self-portraits done the way Hayashi does them are not easy to pull off. The levitation part is straightforward enough: she jumps. But catching herself on camera mid-jump, in a pose that looks levitation-like, floaty and non-jumpy, requires a little technique and a lot of patience.

Hayashi says she puts her camera on a tripod and composes the shot, setting the focus for where she plans to do her jumping. Her shutter speed is very fast, to freeze motion. Her camera can be set for a ten-second delay, allowing her ten seconds to run from the tripod to the jump location; at precisely the right fraction of a second, just before the shutter clicks, she leaps into the air.

Then she goes back to the camera and does it again till she gets it right. Her internal clock must be pretty damn good by now, after working on levitating self-portraits for more than a year, but even so, it is hard to predict exactly which part of a jump the shutter will happen to record, and perhaps hard to anticipate what that part of a jump will look like, composition-wise.

Also, after all that jumping, if her legs were once a bit yowayowa, they are surely yowayowa no more.

Japan

photography

Tokyo

(Image credit: Natsumi Hayashi)

May 1, 2012

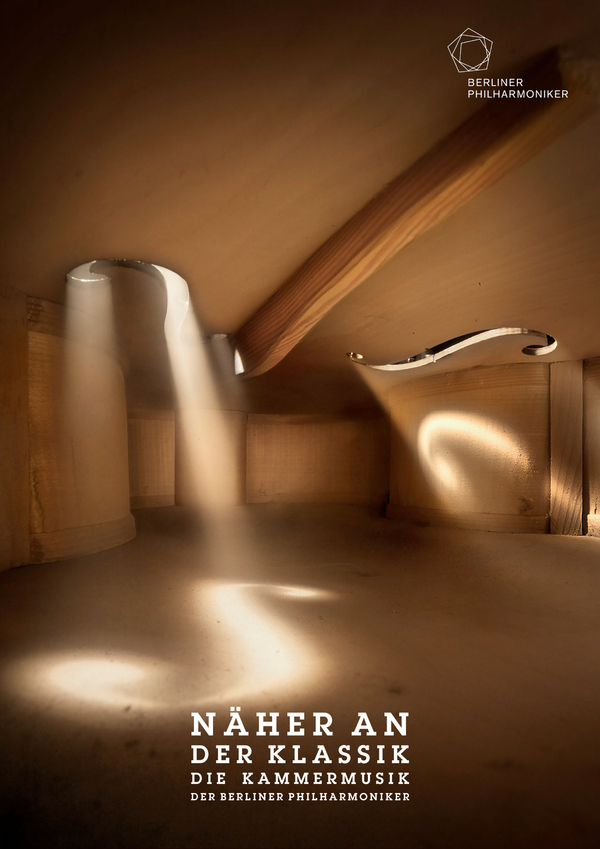

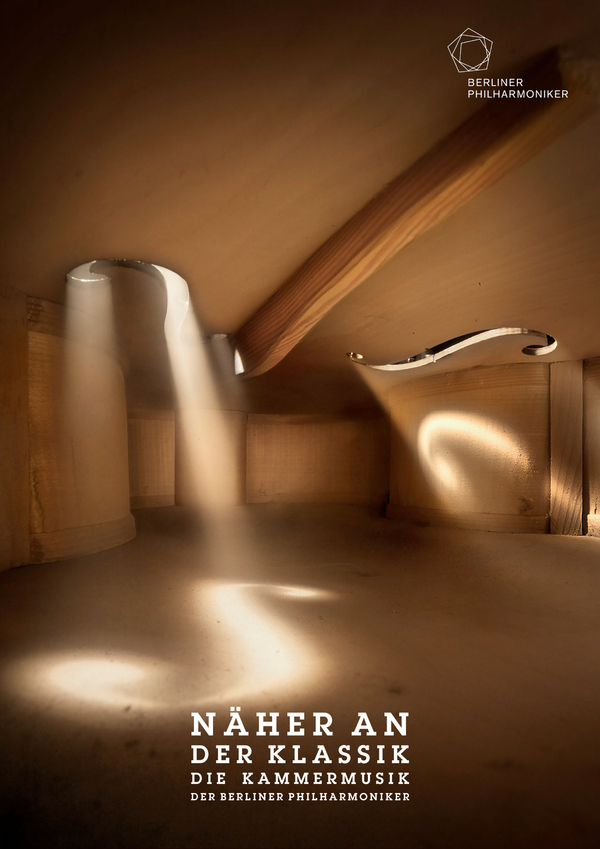

For an advertising campaign to promote the Berlin Philharmonic, Munich photographers Andreas Mierswa and Markus Kluska somehow shot pictures that appear to be looking out, or trying to look out, from inside musical instruments.

For an advertising campaign to promote the Berlin Philharmonic, Munich photographers Andreas Mierswa and Markus Kluska somehow shot pictures that appear to be looking out, or trying to look out, from inside musical instruments.

music

(h/t: JJ)

photography

advertising

Berlin Philharmonic

(Image credits: Mierswa-Kluska

Mona Sibai

Bjorn Ewers)

May 30, 2012

A photo shoot at the mall in the city of Barnaul, Siberia.

A photo shoot at the mall in the city of Barnaul, Siberia.

Siberia

photography

Barnaul

mall

Oct 4, 2012

It's now been about two years since Vivian Maier's photographic oeuvre was discovered among the contents of a storage locker that was auctioned off in Chicago. Hundreds of the pictures have now been published in a book and shown in galleries in New York and Chicago. Dozens are posted on a website, VivianMaier.com. She is the subject of a documentary film project. Hundreds of rolls of film she shot have yet to be developed, and perhaps a hundred thousand of her negatives have yet to be printed.

It's now been about two years since Vivian Maier's photographic oeuvre was discovered among the contents of a storage locker that was auctioned off in Chicago. Hundreds of the pictures have now been published in a book and shown in galleries in New York and Chicago. Dozens are posted on a website, VivianMaier.com. She is the subject of a documentary film project. Hundreds of rolls of film she shot have yet to be developed, and perhaps a hundred thousand of her negatives have yet to be printed.

For fifty years, Maier worked as a nanny, first in New York and then in Chicago. Whenever she got a day off, she took her camera out on the street and shot pictures of the people she encountered. She spent all her earnings on cameras and film, and occasionally on travel to places she wanted to photograph. She became technically skillful, with a sophisticated eye for composition and drama. But she never showed her photographs to anyone.

In her later years, she fell on very hard times and became homeless. Shortly before her death in 2011, she was rescued by three Chicagoans who'd grown up under her care; by then, however, her financial struggles had forced her to sell off one of four storage lockers containing her life's work. The purchaser of the locker was a real estate developer named John Maloof, who'd thought he was buying old snapshots of his neighborhood. When he began to realize what he'd stumbled across, he set aside his regular work and devoted all his time to trying to track down the photographer.

Maier, born in 1926, was still alive in 2010 when Maloof began his search but had died before he could find her. We can't know what she would have thought of the whole world now having a look at the pictures she kept secret for so long. But at least we can look.

New York

Chicago

1950s

photography

portraits

streetscapes

(Image credits: Vivian Maier

Sep 29, 2013

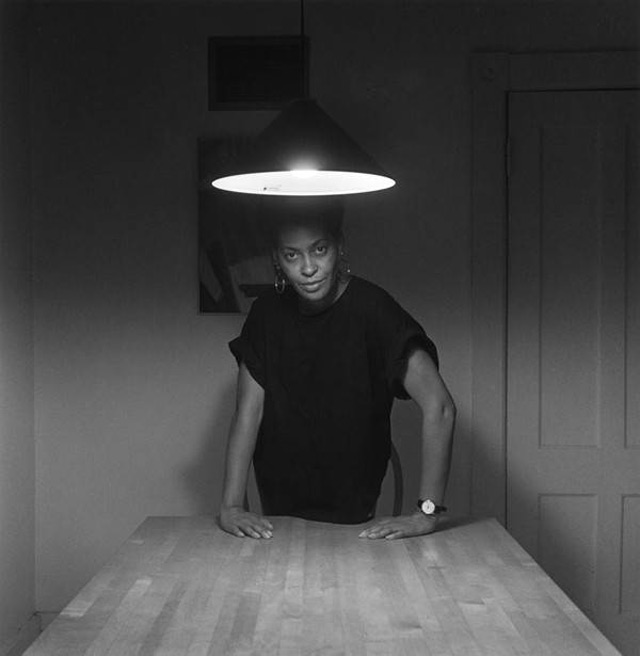

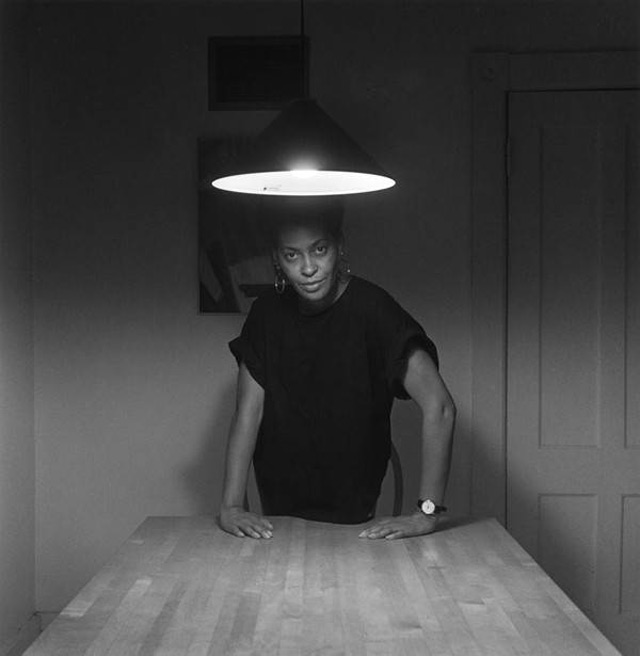

Among this year's winners of genius grants announced last week by the MacArthur Foundation is photographer Carrie Mae Weems. These self-portraits are from her 1990 project, Kitchen Table Series.

Among this year's winners of genius grants announced last week by the MacArthur Foundation is photographer Carrie Mae Weems. These self-portraits are from her 1990 project, Kitchen Table Series.

photography

1990

self-portraits

MacArthur Fellow

(Image credits: Carrie Mae Weems)

Oct 25, 2013

We went to Chicago last weekend for a family wedding, a proverbial happy occasion. The town was bustling with big goings-on; for example, the night before "our" event, there was another wedding at the same downtown hotel, a high-concept sort of wedding in which the bride and everyone else was wearing black. Also at our hotel, an MLS soccer team had taken up residence, visiting from Toronto for a game against the Chicago Fire (the Fire won, 1-0).

We went to Chicago last weekend for a family wedding, a proverbial happy occasion. The town was bustling with big goings-on; for example, the night before "our" event, there was another wedding at the same downtown hotel, a high-concept sort of wedding in which the bride and everyone else was wearing black. Also at our hotel, an MLS soccer team had taken up residence, visiting from Toronto for a game against the Chicago Fire (the Fire won, 1-0).

And then there was the happy occasion seen here, which included a Saturday morning photo session in front of Millennium Park's "Cloud Gate," aka the bean.

Seven years ago, when this tourist magnet first opened, photographers were required to get $350 permits and schedule their shoots in advance. Annish Kapoor, the artist who designed the bean, controlled his work's copyright and attempted to limit its reproduction. But the bean is nothing if not a photo op, and Kapoor quickly had to back off his restrictions; currently, you don't need a photo permit unless you are part of a film crew of ten or more people. The thousands of visitors every day who pull out their cellphones aren't breaking any laws.

The perfect shine and complex globular shape of the bean were inspired by drops of mercury, according to Kapoor, an Indian-born British sculptor. He thinks the popular name for his work, bean, is idiotic. He named it "Cloud Gate" because most of its polished stainless steel surface reflects, and distorts in odd ripply ways, sky and skyscrapers. Visitors are mostly interested, however, in how it reflects them, especially in the arched middle section, which reflects reflections of reflections in crazy, curvy ways much too complicated to figure out.

The plaza in which the bean sits is actually the roof of a restaurant and parking garage, and it had to be seriously reinforced to support 110 tons of highly polished stainless steel. After the reinforcing, computer-aided robots spent a year bending and welding together 168 steel plates, and after the welding, a crew of humans with sandpaper spent more than a year polishing the plates. After all the polishing, the welding seams became completely invisible, an accomplishment that won the work an Extraordinary Welding Award from the American Welding Society.

The lower part of the bean, where people leave fingerprints, is washed every day with Windex. The upper part, where air pollution and birds jeopardize the polish, is washed twice a year with liquid Tide.

If you want to rent it for a day just for yourself and your friends, the city charges $800,000. Twice so far, since opening day in 2006, people have paid that rent. The rest of the time, everybody's welcome, free of charge.

Chicago

wedding

sculpture

construction

photography

Cloud Gate

public art

Annish Kapoor

Millennium Park

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Nov 10, 2014

Self-portrait of the artist as three young girls, in Athens, Greece.

Self-portrait of the artist as three young girls, in Athens, Greece.

Greece

streetscape

photography

Athens

selfie

(Image credit: Ozyxy)

Feb 17, 2016

They were newlyweds in 1905, honeymooning at the beach in St. Augustine, Florida, when they came across the photographer and his props in the sand. And they decided to get their picture made.

So the bride, in her bathing costume, straddled the donkey. And the groom, in his own bathing garb, settled himself onto the seat of the little wagon hitched up to the goat. The props were obviously intended for small children, but the newlyweds were game, even if they didn't look one bit happy about it all.

beach

1905

Florida

wagon

photography

donkeym goat

St. Augustine

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Company via Shorpy)

Jan 7, 2017

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

He grew up hating school, though in about 1930 he did manage to stick out one semester at the University of Toledo, where he said he learned nothing interesting or useful. Over the succeeding 80 or so years, he taught himself whatever he felt like learning, whenever he felt like learning it.

He especially liked new technology, the latest thing. When he was a little boy, the latest thing was a Kodak Brownie camera, which cost one dollar; Olson taught himself to shoot pictures, and he set up a darkroom to develop and print them.

By 1930, the new thing was radio. Olson taught himself to fix radios, to build them, to build better ones. He started a one-man repair shop. By 1963, when he retired on his fiftieth birthday, his little shop had become Olson Electronics, a nationwide chain of 95 stores plus a mail order business, selling parts for radios and every other kind of electronic gizmo. Olson sold his company to a corporation that turned it into Radio Shack.

Long after he retired, he continued fiddling with and teaching himself all about new technological developments. He'd been a photographer all along, publishing travel photos and many others, but at the age of 79 he decided he had to make the switch to digital cameras and computerized photo processing. He taught himself Photoshop when he was in his nineties.

Everything came together for Olson at the age of 97. By then, he'd been retired for almost half a lifetime. He'd outlived his wife of 71 years and settled into an apartment in a senior-living community in Arizona. He'd finally stopped traveling, after visiting 135 different countries; airports were just too unpleasant, he said.

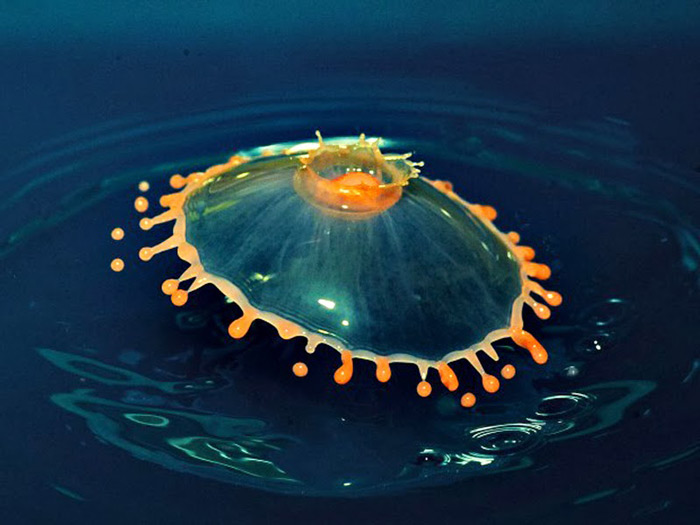

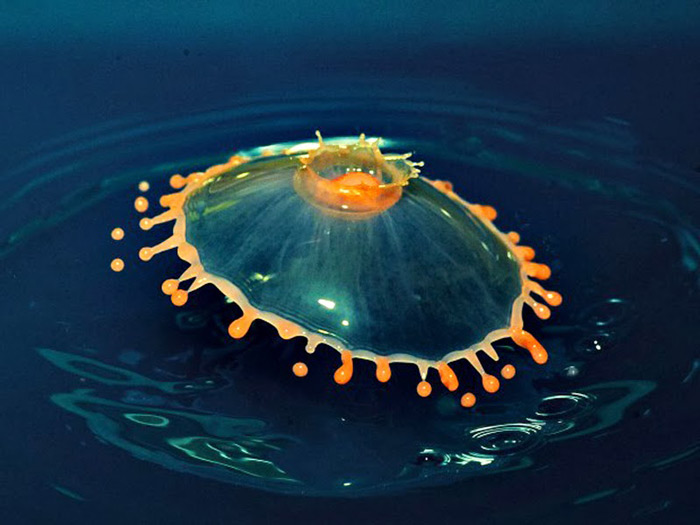

But he was still up for a challenge. And that was when he spotted an article in a technical photography journal about shooting photos of the collision of two drops of water. "I could do that," Olson thought to himself. "In fact, if I color the water, I can make it really interesting."

He turned his kitchen into a lab and got to work. After two years of experimentation, he finally had a setup that reliably produced nice pictures of drops of water banging into each other, some of them really interesting. In this context, "some of them" means that he considered about 1 picture in 500 worth keeping.

When a drop of water falls into a pan of water, it actually bounces a little, about two inches. If a second drop is released so it falls onto the first drop just at the top of the bounce, you might have a good picture. Olson experimented with timing, with lighting, with the size of the drops, with colors, with milk and other additives to change viscosity.

"If you think this is complex, it is," he told the editors at Smithsonian magazine. "If it is almost impossible, I like it a lot."

His photos have been exhibited all over the world, including a one-man show in New York's Grand Central Station. When he turned 100, the University of Akron awarded him an honorary doctorate.

Basically, Olson spent the final years of his life in a darkened kitchen–not all that different from the photographic darkrooms of his early years–fiddling with a drippy faucet kind of thing. By all accounts, it made him really, really happy.

photography

water

Irving Olson

experimentation

Radio Shack

centenarian

Olson Electronics

(Image credits: Irving Olson)

Feb 12, 2017

A sample of lint from the trap in our clothes dryer yielded this strand of something: a hair, maybe, or some kind of fiber that is fixing to fail.

A sample of lint from the trap in our clothes dryer yielded this strand of something: a hair, maybe, or some kind of fiber that is fixing to fail.

We examined the lint with a scanning electron microscope, which magnified it about 927 times by shooting electrons at it and noting how they bounced back. If we'd had a regular old optical microscope, we might have been able to reach this same level of magnification, though we'd be approaching the upper limits of that technology.

Electron microscopes can detect details hundreds of times smaller than optical scopes because electrons travel in more or less straight paths while visible light undulates in waves. The downside is that electrons can't see in color and can't travel much beneath the surface of things, no matter how transparent or translucent that surface might be.

All in all, however, if lint is what you're wanting to look at, then a scanning electron microscope might be just the tool for the job.

With its help, we calculated the width of this strand of whatever it is at about 20 microns–about one fiftieth of a millimeter. The hairs on our heads are usually more like 50 microns in diameter, so this probably isn't that.

This strand of whatever it is has obviously been through the wringer, even though our current washing machine doesn't have a wringer. The strand has been stressed, and were it not for a couple of microns of badly fraying inner strength at its core, it would have snapped completely.

Which does lead to speculation that what we're looking at here is My Last Nerve. . . .

But there are some other possibilities. Such as dog hair: dog hairs average about 25 microns in diameter, more or less in the same ballpark as this strand. Dog hairs often show a scaly pattern on their outer cuticles that looks kinda like the faint pattern we can sorta make out on what's left of the outer surface of this thing. And of course, finding a dog hair in the lint trap at our house, or pretty much anywhere else in our house, isn't completely freakish.

But really: could a dog hair get this mangled and shredded just from normal laundry processes? We want to beg off from a definitive answer; although we've worn many different hats over the years, we have never, ever presented ourselves as expert in the forensic analysis of dog hairs.

We've not yet, however, run out of options. Couldn't this thing be a fabric fiber from some item of clothing?

That electron microscope sure did come in handy.

laundry

hair

photography

Seattle

micrography

forensics

North Seattle College

scanning electron miscroscope

fiber

lint

(Image credit: North Seattle College Nanotechnology Lab)

Feb 14, 2017

The harsh, moody climate and mysterious, treeless landscapes that define the western Nordic islands–Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Islands–are swept up somehow and transformed by imagination into a fashion sensibility, the focus of the Third Nordic Fashion Biennale.

The harsh, moody climate and mysterious, treeless landscapes that define the western Nordic islands–Iceland, Greenland, the Faroe Islands–are swept up somehow and transformed by imagination into a fashion sensibility, the focus of the Third Nordic Fashion Biennale.

Curators Sarah Cooper and Nina Gorfer–American and Austrian by birth, Stockholm-based photographers by choice–have produced an exhibition, book, and film they call The Weather Diaries, which explore fashion as a wind-blown wonder.

landscape

Iceland

fashion

photography

style

Faroe Islands

The Weather Diaries

Greenland

(Image credits: Cooper & Gorfter)

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

For an advertising campaign to promote the Berlin Philharmonic, Munich photographers Andreas Mierswa and Markus Kluska somehow shot

For an advertising campaign to promote the Berlin Philharmonic, Munich photographers Andreas Mierswa and Markus Kluska somehow shot

Among this year's winners of genius grants announced last week by the MacArthur Foundation is photographer Carrie Mae Weems. These self-portraits are from her 1990 project, Kitchen Table Series.

Among this year's winners of genius grants announced last week by the MacArthur Foundation is photographer Carrie Mae Weems. These self-portraits are from her 1990 project, Kitchen Table Series.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.

Among the shining lights lost to the world in 2016 was Irving Olson, a Toledo, Ohio, man who died in his sleep just shy of his 103rd birthday.