Hole in the Clouds

Sep 21, 2009

In the small but earnest world of competitive badminton, the Chicago Open is a big deal, a tournament sanctioned by the body that will select the Olympic badminton team. Some of us forget that badminton is an Olympic sport.

Katrin Maldre is new to the competitive version of the sport and feared she wasn't yet playing at the Chicago Open level, but she took first place yesterday at this year's tournament. There were four divisions, from A, the strongest, through D, the weakest, and Katrin won the D division. Still, she noted, "the picture says it all."

What helped her compensate for badminton inexperience was a lifetime of athletic engagement. At the age of six, she was selected for intensive sports training by the Soviet athletic academy, and as a teenager she joined Estonia's national table tennis team, which competed in all the Soviet Republics across Europe and Asia. In recent years, she's played tennis, skiied, dabbled in recreational soccer, even tried a little bit of mountain climbing.

"There's just something magic about sports events," she says. "Also, while I play I don't eat, I get a lot of exercise, and I don't say any bad words, so I improve myself. And maybe that helps to improve the world a little bit."

sports

Chicago

badminton

Katrin Maldre

(Image credit: Katrin Maldre)

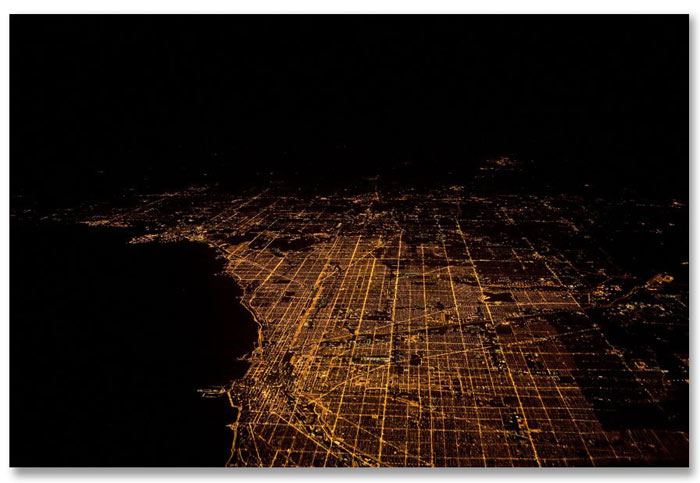

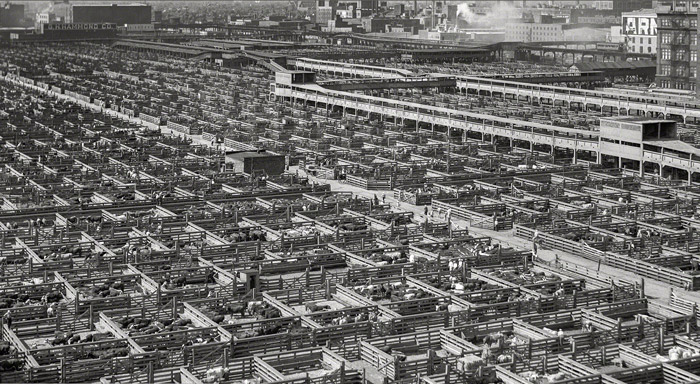

Dec 6, 2009

On a clear night, Chicagoland looks pretty spectacular from the air.

cityscape

Chicago

birdseye view

night

Nov 4, 2010

Today and tomorrow our focus is on beautiful Chicago, in scenes captured by the Polish photographer Krzycho. Here, a few blocks north of downtown, the morning sun is coming up over Lake Michigan, behind the skyscrapers, which seem quite artfully arranged.

Krzycho lives and shoots in Chicago but comes originally from Zamość in southeastern Poland. Clearly, he (or she?) is smitten by the windy city.

cityscape

Chicago

dawn

skyline

skyscrapers

clouds

(Image credit: Krzycho)

Nov 5, 2010

Today's picture is a second offering from Krzycho, this one featuring trains on their way out of Chicago.

cityscape

Chicago

trains

(Image credit: Krzycho)

Aug 1, 2011

The Windy City has a new statue: a cast-aluminum Marilyn Monroe, 26 feet tall, in her Seven-Year Itch subway-grating pose, skirts afly. God and everybody can see her underpants, and tourists on Michigan Avenue can look up at her from between her legs. She'll be there through next spring, we're told, though the installation is called "Forever Marilyn."

The Windy City has a new statue: a cast-aluminum Marilyn Monroe, 26 feet tall, in her Seven-Year Itch subway-grating pose, skirts afly. God and everybody can see her underpants, and tourists on Michigan Avenue can look up at her from between her legs. She'll be there through next spring, we're told, though the installation is called "Forever Marilyn."

Meanwhile, across the sea, in the Norwegian cruise ship port of Haugesund, a bronze more-or-less-lifesized Marilyn Monroe sits harborside, dressed in what appears to be a very short, very wet little cocktail dress with the straps slipping down off her shoulders. Like her Chicago cousin, she is wearing glimpsable underpants, and she's got one shoe on, one shoe off.

The town of Haugesund claims Marilyn on the theory that native son Martin Mortensen was her father. He had emigrated to America in the early twentieth century and married Marilyn's mother. But the couple divorced in 1924, two years before the birth of baby Norma Jean Mortensen, and he had abandoned the family years before that. It seems to be widely believed–except, of course, in Haugesund–that Marilyn / Norma Jean was fathered by somebody else.

On the mythological level, however, the Norwegian connection works. The overall character of Marilyn's short, sad life seems to reprise her mother's story, which ended in a state mental institution, to which she was committed when Marilyn was a baby. Maybe her mother, in her last troubled years, had attempted to reconcile with Martin Mortensen, just as Marilyn in her last days had been planning to re-wed Joe DiMaggio.

A couple things are clear. One, she wasn't really a blonde. And two, American exceptionalism does not require Marilyn Monroe's underpants in the public square. Both statues, but especially the oversized Chicago version, are creepy. At least the Norwegian Marilyn is sad and bedraggled, much as we remember the real star. But the Chicago Marilyn is comic-book iconography, the sexuality so outsized and the sexism so aggressive that the painted smile doesn't hide a thing.

Creeps me out. Obviously, I'm an old fuddy-duddy.

Chicago

Illinois

Marilyn Monroe

Forever Marilyn

Haugesund

subway grating

Norway

Norma Jean Mortensen

(Haugesund photo: Andrew Petcher)

(Chicago photo: Katrin Maldre)

Dec 18, 2011

Visitors enjoy their reflections in the bean, in downtown Chicago's Millennium Park, near the waterfront. The couple pictured here can also be seen at lower right in the picture below, when they were first approaching the shiny thing and had not yet found themselves in it. But they're already there, if you look closely, along with the skyscrapers in the background and an ice skating rink in the middle distance.

Visitors enjoy their reflections in the bean, in downtown Chicago's Millennium Park, near the waterfront. The couple pictured here can also be seen at lower right in the picture below, when they were first approaching the shiny thing and had not yet found themselves in it. But they're already there, if you look closely, along with the skyscrapers in the background and an ice skating rink in the middle distance.

cityscape

Chicago

sculpture

skyline

Millennium Plaza

Grant Park

Cloud Gate

reflections

the bean

parkscape

Jan 23, 2012

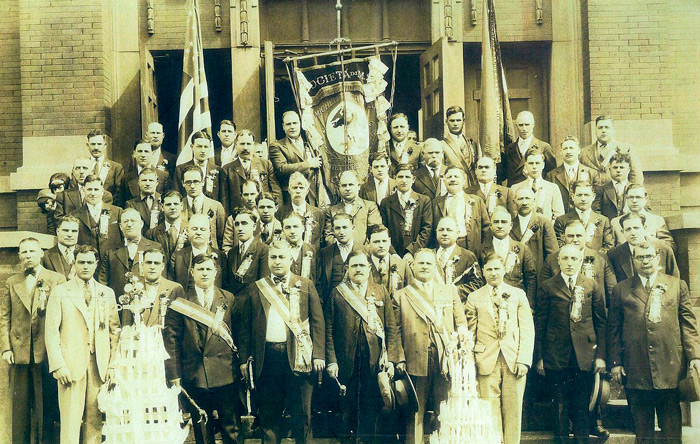

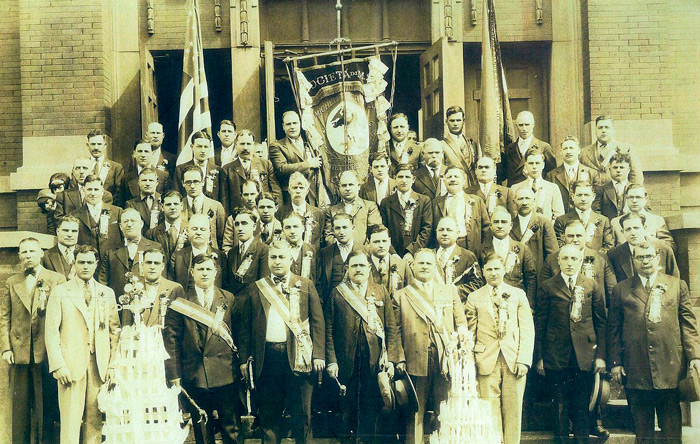

They called themselves the Society of St. Michael the Archangel, a name they took from their parish church back home in Albidona, a small town on the southern coast of Italy, about midway between the heel and toe of the "boot."

They called themselves the Society of St. Michael the Archangel, a name they took from their parish church back home in Albidona, a small town on the southern coast of Italy, about midway between the heel and toe of the "boot."

But in 1926, when this picture was taken, they were all living in Chicago, surrounded by native-born Americans and immigrants from all over Italy and the world. In America, the immigrants from Albidona naturally turned to one another for social life and mutual aid, a hometown bond they formalized with the establishment of the Society of St. Michael the Archangel. Similar benevolent and social organizations based on hometown roots were formed by immigrants in communities all over America, supporting one another socially, culturally, and oftimes financially.

These societies faded in importance as their members established themselves in their new country. Today, however, new groups of immigrants, such as the Sudanese refugees in Maine, are again creating formal organizations for exactly the same purposes. As ever, they function as social centers but also as banks, raising money both to lend to members in need and to send back home for communities in distress.

The gentleman in the middle of the front row with the gavel, presumably the president of the Society of St. Michael in 1926, has been identified as Leonardo Adduci, whose great-grandson shares the photo.

Chicago

Italy

immigrants

Albidona

1926

(via Shorpy)

Aug 12, 2012

A peregrine falcon takes in a February sunrise from the railing of an apartment balcony in Chicago.

A peregrine falcon takes in a February sunrise from the railing of an apartment balcony in Chicago.

Chicago

birdseye view

winter

bird

peregrine falcon

balcony

sunrise

(Image credit: Archie Florcruz; h/t: Whateverland.com)

Sep 23, 2012

That would be the band! The scene of this marching is the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, but bands are everywhere in the fall, parading down the street and then stepping out spectacularly onto the fields of glory. The inimitable Professor Harold Hill of Gary, Indiana, whose Think Method of musical instruction worked well enough till his encounter in Iowa with Marian the librarian, probably said it best: "I always think there's a band, son."

That would be the band! The scene of this marching is the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, but bands are everywhere in the fall, parading down the street and then stepping out spectacularly onto the fields of glory. The inimitable Professor Harold Hill of Gary, Indiana, whose Think Method of musical instruction worked well enough till his encounter in Iowa with Marian the librarian, probably said it best: "I always think there's a band, son."

music

Chicago

streetscape

high school

Pilsen

band

(Image credit: Archie Florcruz)

Oct 4, 2012

It's now been about two years since Vivian Maier's photographic oeuvre was discovered among the contents of a storage locker that was auctioned off in Chicago. Hundreds of the pictures have now been published in a book and shown in galleries in New York and Chicago. Dozens are posted on a website, VivianMaier.com. She is the subject of a documentary film project. Hundreds of rolls of film she shot have yet to be developed, and perhaps a hundred thousand of her negatives have yet to be printed.

It's now been about two years since Vivian Maier's photographic oeuvre was discovered among the contents of a storage locker that was auctioned off in Chicago. Hundreds of the pictures have now been published in a book and shown in galleries in New York and Chicago. Dozens are posted on a website, VivianMaier.com. She is the subject of a documentary film project. Hundreds of rolls of film she shot have yet to be developed, and perhaps a hundred thousand of her negatives have yet to be printed.

For fifty years, Maier worked as a nanny, first in New York and then in Chicago. Whenever she got a day off, she took her camera out on the street and shot pictures of the people she encountered. She spent all her earnings on cameras and film, and occasionally on travel to places she wanted to photograph. She became technically skillful, with a sophisticated eye for composition and drama. But she never showed her photographs to anyone.

In her later years, she fell on very hard times and became homeless. Shortly before her death in 2011, she was rescued by three Chicagoans who'd grown up under her care; by then, however, her financial struggles had forced her to sell off one of four storage lockers containing her life's work. The purchaser of the locker was a real estate developer named John Maloof, who'd thought he was buying old snapshots of his neighborhood. When he began to realize what he'd stumbled across, he set aside his regular work and devoted all his time to trying to track down the photographer.

Maier, born in 1926, was still alive in 2010 when Maloof began his search but had died before he could find her. We can't know what she would have thought of the whole world now having a look at the pictures she kept secret for so long. But at least we can look.

New York

Chicago

1950s

photography

portraits

streetscapes

(Image credits: Vivian Maier

Dec 2, 2012

At Macy's in Chicago, upstairs and downstairs, the season is upon us.

At Macy's in Chicago, upstairs and downstairs, the season is upon us.

Chicago

store

Christmas

shopping

Macy's

fisheye

(Image credit: Archie Florcruz)

Mar 21, 2013

On a cold night in January, more than two hundred firefighters from all over Chicago battled a huge blaze in the Harris Marcus warehouse in the city's Bridgeport district. The job was complicated by extreme cold, as hydrants froze and ladders iced up; the water department was called in to de-ice the ladders with steamers.

On a cold night in January, more than two hundred firefighters from all over Chicago battled a huge blaze in the Harris Marcus warehouse in the city's Bridgeport district. The job was complicated by extreme cold, as hydrants froze and ladders iced up; the water department was called in to de-ice the ladders with steamers.

The next day, embers in the smouldering ruin reignited, and firetrucks had to go back there and spray even more water.

cityscape

Chicago

birdseye view

Illinois

winter

ice

fire

night and day

(Image credit: Archie Florcruz)

Apr 29, 2013

Two women wait for the streetcar in front of a Chicago store window in the summer of 1941.

Two women wait for the streetcar in front of a Chicago store window in the summer of 1941.

Chicago

streetscape

hats

portraits

1941

trolley

streetcar

(Image credit: John Vachon via Shorpy)

Oct 22, 2013

A few hours before the really big moment on Saturday evening, our niece Melissa–now Mrs. Matthew Solomon–enjoyed a little moment with her Grandma Helen.

family

Chicago

wedding

Melissa Koehler Solomon

Helen Ruskin Stein Behr

nieces

(via Facebook)

Oct 25, 2013

We went to Chicago last weekend for a family wedding, a proverbial happy occasion. The town was bustling with big goings-on; for example, the night before "our" event, there was another wedding at the same downtown hotel, a high-concept sort of wedding in which the bride and everyone else was wearing black. Also at our hotel, an MLS soccer team had taken up residence, visiting from Toronto for a game against the Chicago Fire (the Fire won, 1-0).

We went to Chicago last weekend for a family wedding, a proverbial happy occasion. The town was bustling with big goings-on; for example, the night before "our" event, there was another wedding at the same downtown hotel, a high-concept sort of wedding in which the bride and everyone else was wearing black. Also at our hotel, an MLS soccer team had taken up residence, visiting from Toronto for a game against the Chicago Fire (the Fire won, 1-0).

And then there was the happy occasion seen here, which included a Saturday morning photo session in front of Millennium Park's "Cloud Gate," aka the bean.

Seven years ago, when this tourist magnet first opened, photographers were required to get $350 permits and schedule their shoots in advance. Annish Kapoor, the artist who designed the bean, controlled his work's copyright and attempted to limit its reproduction. But the bean is nothing if not a photo op, and Kapoor quickly had to back off his restrictions; currently, you don't need a photo permit unless you are part of a film crew of ten or more people. The thousands of visitors every day who pull out their cellphones aren't breaking any laws.

The perfect shine and complex globular shape of the bean were inspired by drops of mercury, according to Kapoor, an Indian-born British sculptor. He thinks the popular name for his work, bean, is idiotic. He named it "Cloud Gate" because most of its polished stainless steel surface reflects, and distorts in odd ripply ways, sky and skyscrapers. Visitors are mostly interested, however, in how it reflects them, especially in the arched middle section, which reflects reflections of reflections in crazy, curvy ways much too complicated to figure out.

The plaza in which the bean sits is actually the roof of a restaurant and parking garage, and it had to be seriously reinforced to support 110 tons of highly polished stainless steel. After the reinforcing, computer-aided robots spent a year bending and welding together 168 steel plates, and after the welding, a crew of humans with sandpaper spent more than a year polishing the plates. After all the polishing, the welding seams became completely invisible, an accomplishment that won the work an Extraordinary Welding Award from the American Welding Society.

The lower part of the bean, where people leave fingerprints, is washed every day with Windex. The upper part, where air pollution and birds jeopardize the polish, is washed twice a year with liquid Tide.

If you want to rent it for a day just for yourself and your friends, the city charges $800,000. Twice so far, since opening day in 2006, people have paid that rent. The rest of the time, everybody's welcome, free of charge.

Chicago

wedding

sculpture

construction

photography

Cloud Gate

public art

Annish Kapoor

Millennium Park

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Oct 26, 2013

In the 1880s, when he was a little boy, there were so many McCormick relatives also named Robert that they called him Bertie. He inherited a townhouse in Chicago, a suburban house in Lake Forest, and a country estate called Cantigny in Wheaton, Illinois, about twenty miles out of town. The flowers amongst the reeds above were blooming last week in Cantigny, which is now a museum and park.

But Robert McCormick's two most significant inheritances from his wealthy and industrious family were reactionary politics and a newspaper, the Chicago Tribune. Tribune editorials ranted against the New Deal and everything else civilized or modern. But McCormick built the paper up into a huge media empire run out of a downtown office tower that he decorated with chunks of rock from other buildings around the world including, as seen below, Westminster Abbey, the Taj Mahal, Hamlet's castle in Denmark, Byron's Chillon in Switzerland, and the Berlin Wall.

Chicago

politics

Robert McCormick

journalism

fascist

reactionary

Tribune

Cantigny

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Oct 27, 2013

Icelandic sculptor Steinunn Thorarinsdottir populated this garden just south of the Art Institute with aluminum and cast iron people.

garden

Chicago

sculpture

trompe l'oeil

Norman

park

iphone

Segways

iPad

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Oct 28, 2013

Maud Humphrey, born in 1868 in upstate New York, educated at New York City's new Art Students League and then, of course, in Paris, was a rare creature in her place and time: a highly successful professional woman who managed to combine a brilliant career with conventional marriage and family life. She married a doctor but out-earned him several times over, producing commercial artwork for immensely popular books, magazines, and advertising campaigns; she specialized in sentimental watercolor illustrations that featured plump children and adorable animals. Think: Gerber baby.

During her student days, Maud had become friends with another aspiring career woman, Grace Hall, a contralto from Illinois who was studying music and beginning a career on the New York opera and concert stage. Grace enjoyed considerable professional success right from the start, performing at Madison Square Garden among other venues, but she soon began to fear that the pressures of a heavy performance schedule were taking a toll on her health. Her eyesight had been weakened by childhood scarlet fever, and the newfangled electric stage lights seemed blinding. She suffered headaches and exhaustion after every show and lasted only a year before returning home to conventional bourgeois domesticity in the suburbs of Chicago. Like her friend Maud, she married a doctor, and also like her she earned substantially more money than her husband, in her case by offering voice and piano lessons to Chicago's nouveau riche.

The two women stayed in touch, and in 1899, when Grace wrote Maud that she was expecting her second child, Maud responded by sending Grace a half-dozen watercolors to decorate her nursery. And Maud had some news of her own: she too was expecting.

That year, both women gave birth to sons: Maud's boy was named Humphrey Bogart, and Grace's was named Ernest Hemingway. Fifty or so years later, Bogart and Hemingway got to know each other during the filming of a Hemingway story, and they figured out their mothers' connection and the provenance of the nursery paintings.

The photo above shows two of the Maud Humphrey watercolors above Ernest Hemingway's baby bed in the family home in Oak Park, just outside Chicago.

Although Grace Hall Hemingway was still alive when her son met the son of her old friend Maud, she may never have learned about the meeting. Hemingway rather famously nursed grievances against his mother and was distant to his family. His main complaint was that his mother was a cold bitch who had emasculated his father by earning too much money and refusing to defer to husbandly authority.

Every summer, when the family vacationed at a lake cabin in Michigan, where Ernest's father loved to hunt and fish, Grace vacationed instead in a cottage across the lake that she had built for herself and her one-time music student Ruth Arnold, who had previously worked as the children's nanny. Grace clearly preferred Ruth's company to that of her husband and six children, even after her husband created a public commotion when he tried to expel Ruth from their property. Ernest's version of the story emphasized a financial angle: he believed that the money his mother had used to build her lake retreat should have been used instead to send him to college.

Humphrey Bogart is alleged to have complained similarly about his own mother, Maud, although many more details of the Hemingway mother-son issues have been thrashed out in public. But one Maud Humphrey legend can definitely be put to rest: no, the young Humphrey Bogart was not the Gerber baby. His mother did paint his likeness for a baby-food advertising campaign, but that was for a different brand.

music

Chicago

art

1899

Oak Park

Ernest Hemingway

motherhood

Humphrey Bogart

Grace Hall Hemingway

Gerber baby

Maud Humphrey Bogart

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Apr 20, 2014

'Twas the night before Easter, and all over town, stuff was getting weird. Above, Chicago; below, Philly.

Chicago

night

streetscape

Easter

Philly

bunny

(h/t: Carolyn Duffy)

Mar 26, 2017

The truth is not hard to believe: these guys were in fact trying for a world record in 1893 when they loaded the sled with more than 36,000 board feet of virgin white pine logs from Ontanagon County in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

The truth is not hard to believe: these guys were in fact trying for a world record in 1893 when they loaded the sled with more than 36,000 board feet of virgin white pine logs from Ontanagon County in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

How did they pile up the load so high? The horses actually did much of the work. The men would lay each log on the ground longside the sled and affix ropes to it that went up and over the load and then back down to the ground on the other side of the sled. That's where the horses were waiting; they would be harnessed to the ropes, and as they were led away from their side of the sled, the ropes would pull the new log up to the top of the heap, guided up the side by angled tracks made from small logs. When the new log reached the top, the men would snag it into place.

How come the sled didn't just sink down in the snow? An ice road had been specially prepared, with the snow sprayed repeatedly with water and allowed to freeze rock-hard. The horses had special shoes with crampons that bit into the ice surface.

Usually, logs hauled this way were taken to a frozen river, awaiting spring, when they'd be floated downstream to a sawmill. But this particular load was pulled for just half a mile by these two horses, to a railroad siding, where the logs and the sled were loaded onto freight cars and shipped to Chicago.

There, at the Michigan pavilion of the 1893 Columbia Exhibition, the load was reassembled, sled and all, treating fairgoers to a glimpse of logging activity in what was then the world's busiest lumber region.

Did they make it into the Guinness Book of Records? We have no idea, but they did claim this was the largest load of lumber in the history of the world.

Note that most of the men here had no gloves, and of course none of them had hard hats.

Chicago

Michigan

logging

winter

horses

work

sled

forest

1893

Ontanagon County

Columbia Exhibition

Upper Peninsula

world record

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Co via Shorpy)

Feb 4, 2018

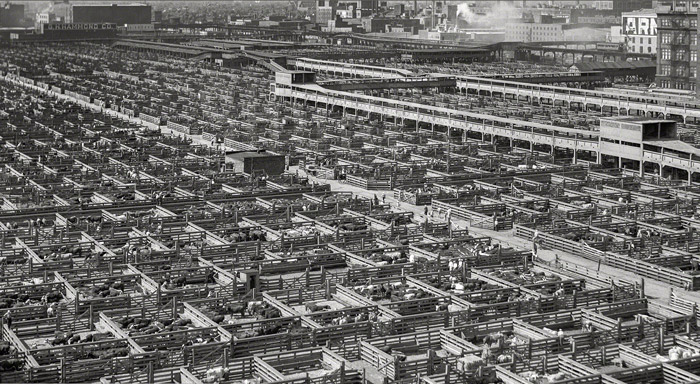

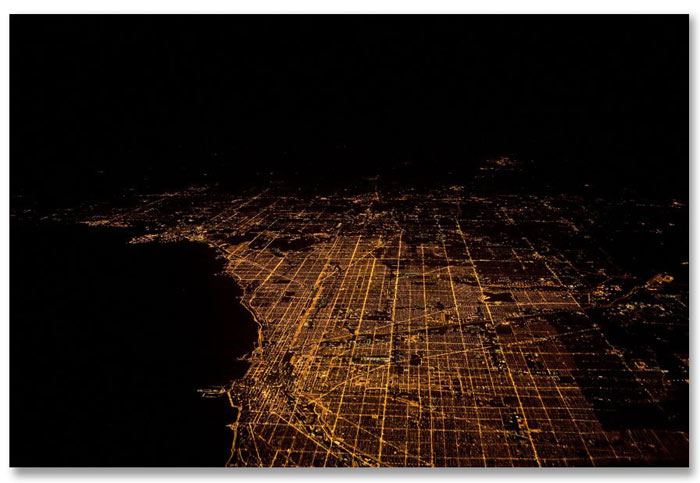

For a hundred years, up until 1971, Chicago's Union Stockyards and surrounding meat-packing plants made the city the meat capital of the universe. The industry gave the neighborhood a definite aroma, but of course, it was still the scent of money.

For a hundred years, up until 1971, Chicago's Union Stockyards and surrounding meat-packing plants made the city the meat capital of the universe. The industry gave the neighborhood a definite aroma, but of course, it was still the scent of money.

The city had to make the Chicago River run backwards in order to keep the animal waste out of municipal drinking water.

The stockyards burned to the ground in 1939, but they'd been newly rebuilt by the time of this photo in 1941.

Chicago

birdseye view

industry

livestock

1941

meatpacking

Union Stockyards

(Image credit: John Vachon)

A peregrine falcon takes in a February sunrise from the railing of an apartment balcony in Chicago.

A peregrine falcon takes in a February sunrise from the railing of an apartment balcony in Chicago. That would be the band! The scene of this marching is the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, but bands are everywhere in the fall, parading down the street and then stepping out spectacularly onto the fields of glory. The inimitable Professor Harold Hill of Gary, Indiana, whose Think Method of musical instruction worked well enough till his encounter in Iowa with Marian the librarian, probably said it best: "I always think there's a band, son."

That would be the band! The scene of this marching is the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, but bands are everywhere in the fall, parading down the street and then stepping out spectacularly onto the fields of glory. The inimitable Professor Harold Hill of Gary, Indiana, whose Think Method of musical instruction worked well enough till his encounter in Iowa with Marian the librarian, probably said it best: "I always think there's a band, son."

At Macy's in Chicago, upstairs and downstairs, the season is upon us.

At Macy's in Chicago, upstairs and downstairs, the season is upon us. On a cold night in January, more than two hundred firefighters from all over Chicago battled a huge blaze in the Harris Marcus warehouse in the city's Bridgeport district. The job was complicated by extreme cold, as hydrants froze and ladders iced up; the water department was called in to de-ice the ladders with steamers.

On a cold night in January, more than two hundred firefighters from all over Chicago battled a huge blaze in the Harris Marcus warehouse in the city's Bridgeport district. The job was complicated by extreme cold, as hydrants froze and ladders iced up; the water department was called in to de-ice the ladders with steamers.

In the 1880s, when he was a little boy, there were so many McCormick relatives also named Robert that they called him Bertie. He inherited a townhouse in Chicago, a suburban house in Lake Forest, and a country estate called Cantigny in Wheaton, Illinois, about twenty miles out of town. The flowers amongst the reeds above were blooming last week in Cantigny, which is now a museum and park.

In the 1880s, when he was a little boy, there were so many McCormick relatives also named Robert that they called him Bertie. He inherited a townhouse in Chicago, a suburban house in Lake Forest, and a country estate called Cantigny in Wheaton, Illinois, about twenty miles out of town. The flowers amongst the reeds above were blooming last week in Cantigny, which is now a museum and park.