Hole in the Clouds

May 22, 2011

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.

The Baltimore seafood packers were immigrant families who called themselves Slovonians; they came mostly from regions of Eastern Europe that would later become Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. After a few years in Baltimore, many relocated to Biloxi, Mississippi, which became the center of American seafood processing through much of the twentieth century. There is still a Slovonian Society and Social Club in Biloxi.

Lewis Hine's photographs of working children were part of his eventually successful campaign to end child labor in the United States. This picture is a bit different, however. If you click on the photo to view a larger version, you will notice that several of the children are clearly too young to pack fish; one is too young to walk. And unlike Hine's usual subjects, some of these children are smiling, even laughing.

Maybe the picture is a reject from the anti–child labor campaign, hence the missing caption. Perhaps the children were families of seafood packers, but not necessarily working themselves as seafood packers. But it is clear from Hine's other photographs that at least some of these children did in fact work long, miserable hours in the wretched factory they are posed in front of. They nonetheless laugh and smile, we have to assume, because that's what children do.

children

Baltimore

work

(h/t: Shorpy)

immigrants

1900

(Image credit: Lewis Hine)

Jan 23, 2012

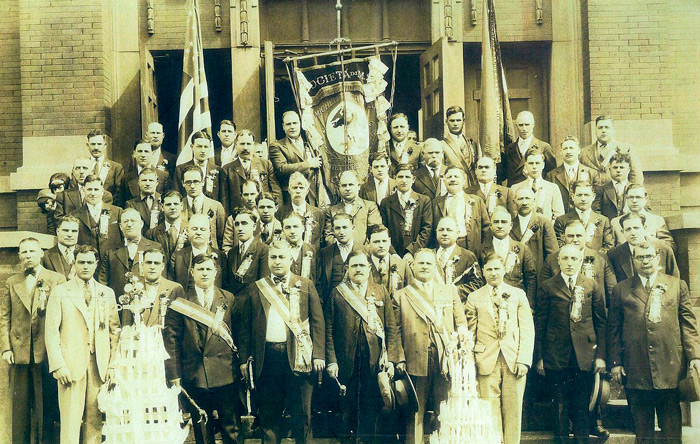

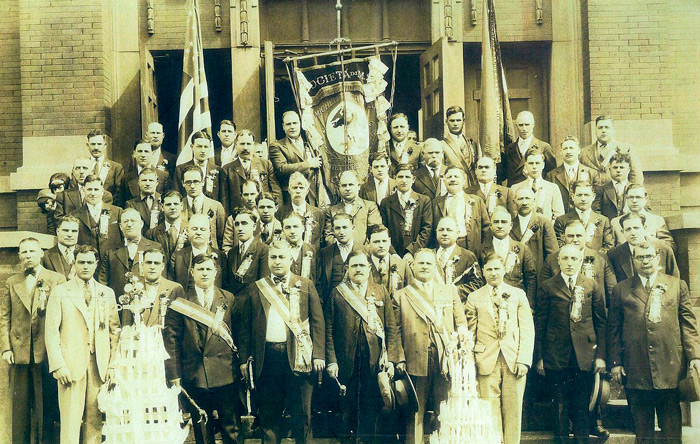

They called themselves the Society of St. Michael the Archangel, a name they took from their parish church back home in Albidona, a small town on the southern coast of Italy, about midway between the heel and toe of the "boot."

They called themselves the Society of St. Michael the Archangel, a name they took from their parish church back home in Albidona, a small town on the southern coast of Italy, about midway between the heel and toe of the "boot."

But in 1926, when this picture was taken, they were all living in Chicago, surrounded by native-born Americans and immigrants from all over Italy and the world. In America, the immigrants from Albidona naturally turned to one another for social life and mutual aid, a hometown bond they formalized with the establishment of the Society of St. Michael the Archangel. Similar benevolent and social organizations based on hometown roots were formed by immigrants in communities all over America, supporting one another socially, culturally, and oftimes financially.

These societies faded in importance as their members established themselves in their new country. Today, however, new groups of immigrants, such as the Sudanese refugees in Maine, are again creating formal organizations for exactly the same purposes. As ever, they function as social centers but also as banks, raising money both to lend to members in need and to send back home for communities in distress.

The gentleman in the middle of the front row with the gavel, presumably the president of the Society of St. Michael in 1926, has been identified as Leonardo Adduci, whose great-grandson shares the photo.

Chicago

Italy

immigrants

Albidona

1926

(via Shorpy)

May 10, 2012

In the eye of Mexican photographer Dulce Pinzon, the superheroes of the twenty-first century include millions of Mexican immigrants in the United States, including Elizabeth and Enrique Alonso, shown here. These men and women show their super-sized courage and devotion when they leave home and family to live among strangers in a strange land, working ferociously hard at the hardest jobs, all so they can send remittances to their families back home. In 2009, when Pinzon dressed the Alonsos as The Fantastic Twins to reveal their superhero status to everybody around them at their workplace, in a Manhattan restaurant, they were sending home $400 a week to support their family in Puebla, Mexico.

In the eye of Mexican photographer Dulce Pinzon, the superheroes of the twenty-first century include millions of Mexican immigrants in the United States, including Elizabeth and Enrique Alonso, shown here. These men and women show their super-sized courage and devotion when they leave home and family to live among strangers in a strange land, working ferociously hard at the hardest jobs, all so they can send remittances to their families back home. In 2009, when Pinzon dressed the Alonsos as The Fantastic Twins to reveal their superhero status to everybody around them at their workplace, in a Manhattan restaurant, they were sending home $400 a week to support their family in Puebla, Mexico.

Mexico

work

immigrants

restaurant

monkey

Elizabeth and Enrique Alonso

(Image credit: Dulce Pinzon)

Feb 15, 2017

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

For their wedding attire, Rose wore a shirtwaist she had sewn herself. Charlie wore a celluloid collar that according to my father was stiff enough to shore up a house. And like many men in 1905, he wore an elaborate mustache. Unlike most men, however, Charlie kept that mustache all his life, and by the 1950s, when I got to know my grandparents, I thought he was the only man on earth who had a mustache.

Charlie never had a job in his life; he thought it would be stupid to work for a boss in a free country. So he started out in Baltimore working for himself, as a peddlar with a sack on his back; eventually, he got a horse and wagon, and then he and Rose went into business together, as equal partners, in a soda water store in a Jewish and Italian neighborhood near the Shot Tower, Baltimore's old cannon-ball works. My father recounted his mother's description of the business:

I used to make the soda; I had to work a hand pump to pump the gas into the water. Then we would serve the seltzer, supply a table and chairs, pay the rent and the light bill, and then I had to wash the glass. For that, I took in exactly one cent. When I did that a hundred times, when I washed a hundred glasses, I took in a dollar.

They learned to speak English, though not really to read or write it, but they spoke Yiddish at home and in the neighborhood. All their lives in America, they got their news from the Daily Forward, a Socialist Yiddish-language newspaper published in New York. They were not Socialists, however; my grandmother's politics were rooted entirely in neighborhood organizations, primarily women's clubs and loan circles, through which poor immigrants helped take care of each other; my grandfather, as a small businessman, understood government basically as a mob at City Hall extorting protection money in the form of taxes. For example, long after he had traded in his horse and wagon for a Chevrolet delivery van, he continued to pay his horse tax every year; he figured he was down in somebody's books for that amount.

They had five children who all grew up in Baltimore and lived there or nearby as adults. Then came sixteen grandchildren, who scattered across the country, from Maine to California. And then dozens of great-grandchildren.

This picture is the oldest family document we have; we have nothing from the old country, no names or stories or objects, with the possible exception of one battered copper pot. I remember thinking to myself when I was growing up that my family just didn't go back very far in time, just didn't have a history at all; in other families, there were ancestors back in the olden days, but the most ancient people I was related to were still alive, still in Baltimore, where that side of my family history seemed to have sprung to life.

Now, however, this is a really old photo, from a wedding more than a century ago. Rose and Charlie are gone, as are all five of their children, my father's generation. We in the cousins' generation are getting on in years now, and most of us don't keep in close touch with one another. But it's undeniable that the family goes way, way back before us.

And there's yet another generation now, Rose and Charlie's great-great grandchildren. Crazy, isn't it, how that keeps happening.

wedding

Baltimore

1905

immigrants

Rose and Charles Horowitz

Lithuania

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.