Hole in the Clouds

Oct 24, 2010

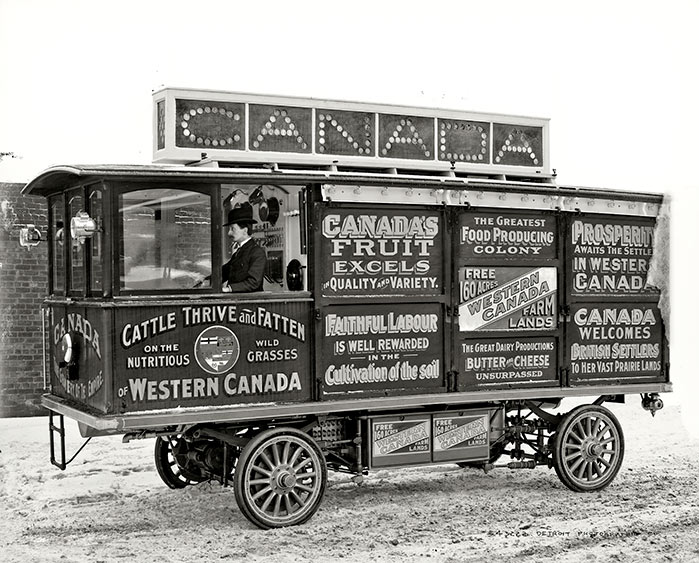

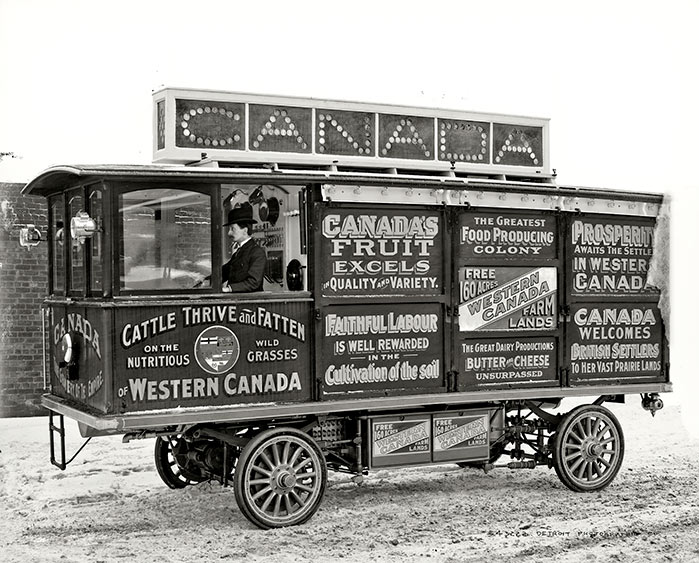

The stereotypical Canadian self-effacement apparently did not play a large part in 1905 in the design of this vehicle, a joint venture between the Canadian Pacific Railway and the governments of the brand new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The motor car was intended to travel the byways of England, promoting immigration to western Canada and, perhaps incidentally, ticket sales on the Canadian Pacific Railway and its trans-Atlantic steamship subsidiary.

The promotional message left out a few details. For one thing, although homesteaders could indeed claim 160 free acres of land, it cost $10 to file the claim, a sum many would-be homesteaders could not come up with after paying the Canadian Pacific for steamship and railway passage. Also, in the, um, bracing climate of the Canadian prairies, 160 acres was not nearly enough land to support a family.

So although the promotional efforts succeeded quickly in populating the prairies--this round of Canadian homesteading was closed off by 1914--most of the homesteaders were ultimately unsuccessful at farming and ranching. Among those few who could stick it out long enough to prove up on their claims, drought years beginning in 1920 ultimately chased them away. Today the Canadian prairie provinces (like the U.S. prairie states) are littered with ghost towns and empty farmhouses.

The vehicle pictured here was a hybrid, powered by electric motors at each wheel and a gas engine that heated a steam boiler. It never did work properly and was abandoned in London.

vintage

Canada

Canadian Pacific Railway

hybrid vehicle

Manitoba

Saskatchewan

1905

(Image credit: via Shorpy)

May 22, 2012

The little girl with the big grin, shown here in Smith County, Tennessee in 1906 or 1907, lived until 2011, when she was 105 years old. The grandchild who submitted the photo to Shorpy titled it "A Rare Smile."

The little girl with the big grin, shown here in Smith County, Tennessee in 1906 or 1907, lived until 2011, when she was 105 years old. The grandchild who submitted the photo to Shorpy titled it "A Rare Smile."

children

Tennessee

portrait

1905

Taylor Thomason

Smith County

longevity

sisters

Mar 12, 2014

It's payday for midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, in 1905.

It's payday for midshipmen at the U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, in 1905.

Annapolis

1905

Naval Academy

midshipmen

(Image credit: Shorpy)

Feb 17, 2016

They were newlyweds in 1905, honeymooning at the beach in St. Augustine, Florida, when they came across the photographer and his props in the sand. And they decided to get their picture made.

So the bride, in her bathing costume, straddled the donkey. And the groom, in his own bathing garb, settled himself onto the seat of the little wagon hitched up to the goat. The props were obviously intended for small children, but the newlyweds were game, even if they didn't look one bit happy about it all.

beach

1905

Florida

wagon

photography

donkeym goat

St. Augustine

(Image credit: Detroit Publishing Company via Shorpy)

Feb 15, 2017

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

For their wedding attire, Rose wore a shirtwaist she had sewn herself. Charlie wore a celluloid collar that according to my father was stiff enough to shore up a house. And like many men in 1905, he wore an elaborate mustache. Unlike most men, however, Charlie kept that mustache all his life, and by the 1950s, when I got to know my grandparents, I thought he was the only man on earth who had a mustache.

Charlie never had a job in his life; he thought it would be stupid to work for a boss in a free country. So he started out in Baltimore working for himself, as a peddlar with a sack on his back; eventually, he got a horse and wagon, and then he and Rose went into business together, as equal partners, in a soda water store in a Jewish and Italian neighborhood near the Shot Tower, Baltimore's old cannon-ball works. My father recounted his mother's description of the business:

I used to make the soda; I had to work a hand pump to pump the gas into the water. Then we would serve the seltzer, supply a table and chairs, pay the rent and the light bill, and then I had to wash the glass. For that, I took in exactly one cent. When I did that a hundred times, when I washed a hundred glasses, I took in a dollar.

They learned to speak English, though not really to read or write it, but they spoke Yiddish at home and in the neighborhood. All their lives in America, they got their news from the Daily Forward, a Socialist Yiddish-language newspaper published in New York. They were not Socialists, however; my grandmother's politics were rooted entirely in neighborhood organizations, primarily women's clubs and loan circles, through which poor immigrants helped take care of each other; my grandfather, as a small businessman, understood government basically as a mob at City Hall extorting protection money in the form of taxes. For example, long after he had traded in his horse and wagon for a Chevrolet delivery van, he continued to pay his horse tax every year; he figured he was down in somebody's books for that amount.

They had five children who all grew up in Baltimore and lived there or nearby as adults. Then came sixteen grandchildren, who scattered across the country, from Maine to California. And then dozens of great-grandchildren.

This picture is the oldest family document we have; we have nothing from the old country, no names or stories or objects, with the possible exception of one battered copper pot. I remember thinking to myself when I was growing up that my family just didn't go back very far in time, just didn't have a history at all; in other families, there were ancestors back in the olden days, but the most ancient people I was related to were still alive, still in Baltimore, where that side of my family history seemed to have sprung to life.

Now, however, this is a really old photo, from a wedding more than a century ago. Rose and Charlie are gone, as are all five of their children, my father's generation. We in the cousins' generation are getting on in years now, and most of us don't keep in close touch with one another. But it's undeniable that the family goes way, way back before us.

And there's yet another generation now, Rose and Charlie's great-great grandchildren. Crazy, isn't it, how that keeps happening.

wedding

Baltimore

1905

immigrants

Rose and Charles Horowitz

Lithuania

Feb 3, 2018

When Philadelphia's Northeast Manual Training School opened its doors in 1905, the idea of a public high school to prepare poor boys to work in modern industrial trades was progressive, even radical. But Philly was booming with industry--in fact, just a block over from the new school building was the Quaker Lace factory, with over a hundred clattering power looms that could be heard in every classroom.

When Philadelphia's Northeast Manual Training School opened its doors in 1905, the idea of a public high school to prepare poor boys to work in modern industrial trades was progressive, even radical. But Philly was booming with industry--in fact, just a block over from the new school building was the Quaker Lace factory, with over a hundred clattering power looms that could be heard in every classroom.

The building itself was collegiate Gothic in style, with gargoyles all around and a crenellated turret in the middle.

The school changed its name and mission several times; it became a comprehensive high school, originally for boys only, named Northeast, until 1957, when a new Northeast High School was built in the new residential district closer to the edge of the city.

Then the building became Edison High, which achieved a particularly sad notoriety: no other high school in America outdid Edison in graduating young menwho were killed in the Vietnam War. Sixty-four Edison alumni are memorialized on a bronze plaque outside the school.

But since 1992, Edison High School has operated in a different building a few blocks away, and that's where the bronze memorial sits today. The original school site was used briefly for a bilingual middle school and then abandoned altogether, like almost all the mills, factories, and foundries that surround it.

In 2010, the lace factory burned to the ground, in an eight-alarm blaze attributed to arson; it is said that drug dealers in the neighborhood burned the long-abandoned structure because they believed police were using it as an observation post.

In 2011, the old Manual Training School building also burned, in a fire also deemed suspicious in origin. The site was under contract to a developer who wanted to put a shopping center there.

Remains of the school were demolished a few months later, but the gargoyles, it was said, were carefully preserved for use somewhere else. Where? We have not been able to find out.

Philadelphia

1905

gargoyle

Northeast Manual Training School

Edison High School

arson

The little girl with the big grin, shown here in Smith County, Tennessee in 1906 or 1907, lived until 2011, when she was 105 years old. The grandchild who submitted the photo to

The little girl with the big grin, shown here in Smith County, Tennessee in 1906 or 1907, lived until 2011, when she was 105 years old. The grandchild who submitted the photo to

When Philadelphia's Northeast Manual Training School opened its doors in 1905, the idea of a public high school to prepare poor boys to work in modern industrial trades was progressive, even radical. But Philly was booming with industry--in fact, just a block over from the new school building was the Quaker Lace factory, with over a hundred clattering power looms that could be heard in every classroom.

When Philadelphia's Northeast Manual Training School opened its doors in 1905, the idea of a public high school to prepare poor boys to work in modern industrial trades was progressive, even radical. But Philly was booming with industry--in fact, just a block over from the new school building was the Quaker Lace factory, with over a hundred clattering power looms that could be heard in every classroom.