Hole in the Clouds

Jan 30, 2010

In 1935, when my father's parents Rose and Charles Horowitz celebrated their thirtieth anniversary, the basic fact of life in America was the Great Depression. Still, to mark the occasion properly, you had to dress up and sit for a formal portrait.

That's Rose and Charles in the middle, of course, with my father, Bobby, the baby of the family, on their laps. He is 85 now and may be the only person in the picture who's still alive. Fortunately, he noted who's who and described everybody for posterity--the woman at the far right, for example, is "cousin Hattie, who became the first radio cab dispatcher in Baltimore."

Three of my father's four siblings are shown here, with their spouses, along with assorted relatives and friends.

Sitting next to my grandmother is her sister Bessie, and standing behind Bessie is Uncle Eli, the subject of today's post. Back in eastern Europe before the turn of the century, Eli had been conscripted into the czar's army and ordered to Siberia; he deserted and somehow found his way to Philadelphia instead, There, he got a job as a furrier, married Bessie, and raised five children. They were poor; my father recalled that in Eli and Bessie's house, he had to be very careful not to use too much soap when he washed his hands.

Some years after this picture was taken, when Eli and Bessie were celebrating their own fiftieth anniversary, Eli went out on the floor with all the young guys and danced the Kazachok, the Russian squatting-and-kicking dance. The family story is that he kicked as hard and danced as fast and lasted as long as anybody half his age. He had a talent for enjoying life, including his schnapps. One of his sons became a doctor, who warned his father not to drink too much; the story is that when the son ordered him to cut back to one glass a day, Eli said fine, but he made sure that his one daily glass was a huge water-tumbler-sized drink. Whatever, he outlived his son the doctor.

Eli had a one-word retirement plan: fishing. And that's exactly what he did; when he was finally too old to stay at work sewing furs, he and Bessie moved to Atlantic City, where every morning he woke up, walked down to the beach, and went fishing. He was in his nineties when I first met him, still the life of the party, and still fishing.

vintage

anniversary

Horowitz family

Uncle Eli

Baltimore

1935

May 22, 2011

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.

The caption is missing from this Lewis Hine photo in the Library of Congress, but it was taken in the year 1900 and is believed to show children who worked at a seafood-packing plant in Baltimore.

The Baltimore seafood packers were immigrant families who called themselves Slovonians; they came mostly from regions of Eastern Europe that would later become Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. After a few years in Baltimore, many relocated to Biloxi, Mississippi, which became the center of American seafood processing through much of the twentieth century. There is still a Slovonian Society and Social Club in Biloxi.

Lewis Hine's photographs of working children were part of his eventually successful campaign to end child labor in the United States. This picture is a bit different, however. If you click on the photo to view a larger version, you will notice that several of the children are clearly too young to pack fish; one is too young to walk. And unlike Hine's usual subjects, some of these children are smiling, even laughing.

Maybe the picture is a reject from the anti–child labor campaign, hence the missing caption. Perhaps the children were families of seafood packers, but not necessarily working themselves as seafood packers. But it is clear from Hine's other photographs that at least some of these children did in fact work long, miserable hours in the wretched factory they are posed in front of. They nonetheless laugh and smile, we have to assume, because that's what children do.

children

Baltimore

work

(h/t: Shorpy)

immigrants

1900

(Image credit: Lewis Hine)

May 2, 2012

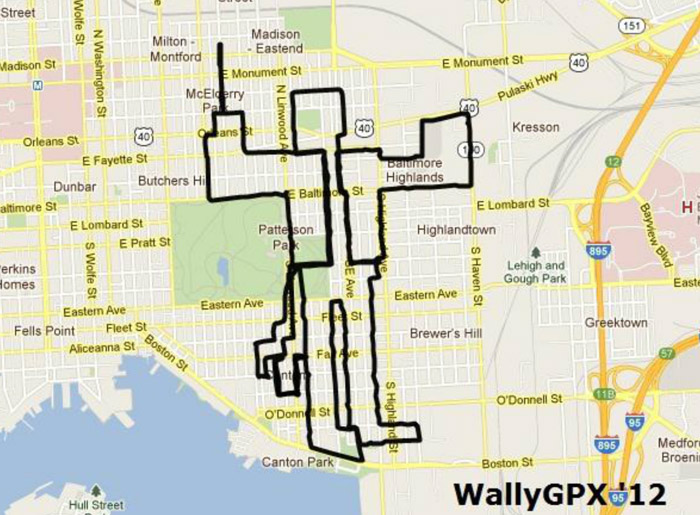

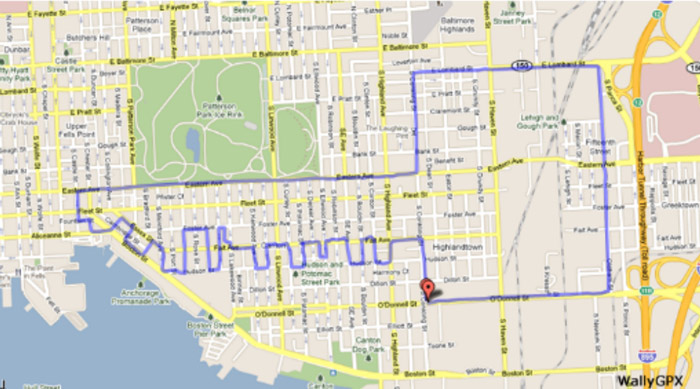

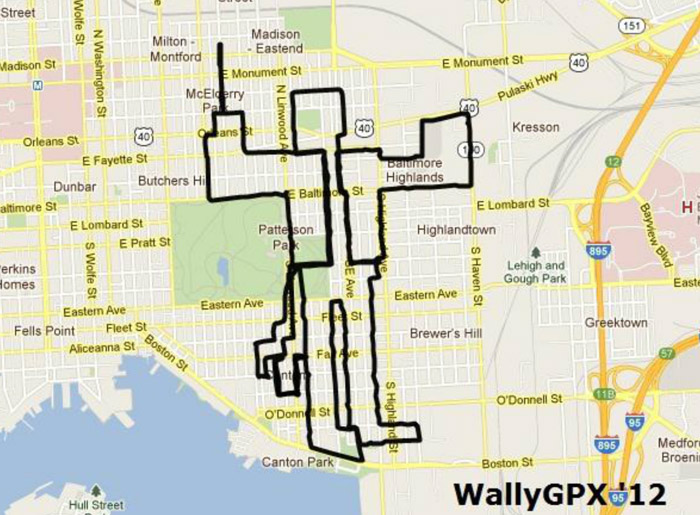

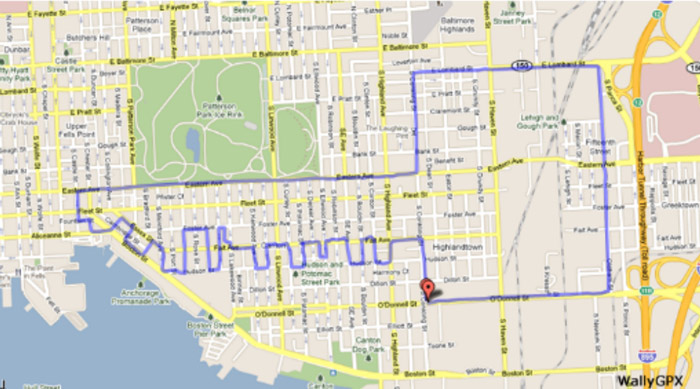

Here we see The Superconductor, a GPS track created a couple of months ago by Michael J. Wallace as he navigated his bicycle through the streets of Baltimore.

Here we see The Superconductor, a GPS track created a couple of months ago by Michael J. Wallace as he navigated his bicycle through the streets of Baltimore.

The track is invisible out on the street, of course; it comes to us as a digital recording (via a GPS app on a cellphone) of the exact path taken by Wallace's bicycle during one of his fitness rides. He designs a different track for each ride, planning it out ahead of time on maps and satellite imagery and then following the route as precisely as possible, even if he has to go the wrong way down a one-way street or retrace part of his path without moving over to the other side of the street.

"Once the recording begins," he says on his website, "a continuous pedal-powered line is created." The line becomes visible only when he gets back home after the ride and checks it out on his computer screen. It's a "virtual geoglyph," he says, painted in sweat on the "local canvas" of his neighborhood.

The geoglyph below, of a Baltimore icon, the Francis Scott key, required 6.25 miles of pedaling on a wretchedly muggy night last summer, when the temperature was 87 degrees. Wallace started the ride listening to Clash in his headphones but soon switched to the Rolling Stones. Tracing the key took 53 minutes and 17 seconds, and along the way he noticed four dead rats in the street and one dead bird.

When he got to the upper righthand corner of the key, the street he was following northward dead ended at the bottom of an embankment. "I had to muscle my bike up a steep hill to catch E. Lombard Street back towards downtown," he noted. "Sometimes that's how the road goes."

bicycle

Baltimore

GPS

Michael J. Wallace

invisible lines

maps

Jun 3, 2012

In 1920, this was Dead Man's Curve on the main highway connecting Washington and Baltimore. The small sign in the middle of the photo, just beyond the wooden guard rail, reads "Danger."

In 1920, this was Dead Man's Curve on the main highway connecting Washington and Baltimore. The small sign in the middle of the photo, just beyond the wooden guard rail, reads "Danger."

Route 1 was rerouted in the 1940s to avoid the danger.

Washington

streetscape

Baltimore

1920

signage

Route 1

highway

(Image credit: National Photo Co.)

Nov 1, 2013

Between 1941 and 1945, more ships were built here at Baltimore's Bethlehem-Fairfield yard than anywhere else on earth. Early in the war, building a Liberty Ship–a clunky freighter using a simple design left over from World War I–took eight months; by 1944, after they'd knocked out a few hundred Liberty Ships and gotten a knack for the work, Baltimoreans could build one in 19 days.

Between 1941 and 1945, more ships were built here at Baltimore's Bethlehem-Fairfield yard than anywhere else on earth. Early in the war, building a Liberty Ship–a clunky freighter using a simple design left over from World War I–took eight months; by 1944, after they'd knocked out a few hundred Liberty Ships and gotten a knack for the work, Baltimoreans could build one in 19 days.

Liberty Ships were slow, awkward cargo vessels intended to last only five years–just long enough, it was hoped, for them to supply our forces overseas with everything needed to win the war: jeeps, tanks, food, ammunition, mail from home, medical supplies. More than 2700 were eventually constructed, all from standardized designs and prefabricated components, at shipyards around the country; 350 were built here in Baltimore, more than in any other single yard.

They weren't pretty–the newspapers called them "Ugly Ducklings"–but they could float.

Next door to the Bethlehem-Fairfield works was another shipyard, Maryland Drydock, where round the clock war work was also under way. At Maryland Drydock, old freighters and passenger liners were refitted to carry troops to war. Racks of bunks were installed in former cargo holds and staterooms, stacked eight deep, with just 18 vertical inches between them. Thousands of soldiers would be crammed into each ship.

Meanwhile, thousands of workmen, including my father, were making fabulous wages of a whole dollar an hour at Maryland Drydock. My father worked as a sheet metal helper there until he got drafted into the army in 1943. His job was to install ductwork in hopes of providing ventilation deep into the holds of cargo ships, where once piles of sugar or bolts of cloth or cases of rum had traveled in relatively airless comfort. The idea was that soldiers on their way to war might want to be able to breathe while jammed together into the new bunks.

By the summer of 1944, my father couldn't have been very surprised when he became a passenger on a troop ship just like the ones he'd worked on at Maryland Drydock. Fifty years later, he wrote about his experience aboard the USS West Point:

As we boarded the ship, each of us was given a paper tag–mine was pink–and that meant I got into the chow line at 2 p.m. and 10 p.m. The cooks started serving Spam and beans as we pulled out of Boston harbor, and they didn't stop, around the clock, until our ship tied up at Liverpool four and a half days later.

On the ship, which was carrying more than 11,000 soldiers and a 1500-man crew, my company was assigned to bunks in the lowest hold. I was given a wooden club, and in the event of an emergency I was supposed to stand at the head of a specified gangway and maintain order.

We all ignored those assignments and simply slept on deck. We didn't want to be below the waterline when the torpedo struck. We lucked out.

Baltimore

World War II

Robert Horowitz

Liberty Ships

troop transport

Maryland Drydock

Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard

(Image credit: Arthur Siegel for Office of War Information, via Shorpy)

Jan 28, 2016

That's the Quiet Man with Norman, at the window of Delia Foley's tavern in Baltimore. He's quiet all right, albeit a little shrunken, not exactly John Wayne–sized. Still and all, anybody who's that solid and bronze has got to have a good, strong shoulder to lean on.

That's the Quiet Man with Norman, at the window of Delia Foley's tavern in Baltimore. He's quiet all right, albeit a little shrunken, not exactly John Wayne–sized. Still and all, anybody who's that solid and bronze has got to have a good, strong shoulder to lean on.

Baltimore

window

Norman

bronze

John Wayne

tavern

(Image credit: Fuji T)

Feb 15, 2017

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

My grandparents Rose and Charlie–my father's parents–posed for this picture on their wedding day in Baltimore in 1905. They were Jewish immigrants from villages just down the road from one another in Lithuania, who had made their way to America as teenagers.

For their wedding attire, Rose wore a shirtwaist she had sewn herself. Charlie wore a celluloid collar that according to my father was stiff enough to shore up a house. And like many men in 1905, he wore an elaborate mustache. Unlike most men, however, Charlie kept that mustache all his life, and by the 1950s, when I got to know my grandparents, I thought he was the only man on earth who had a mustache.

Charlie never had a job in his life; he thought it would be stupid to work for a boss in a free country. So he started out in Baltimore working for himself, as a peddlar with a sack on his back; eventually, he got a horse and wagon, and then he and Rose went into business together, as equal partners, in a soda water store in a Jewish and Italian neighborhood near the Shot Tower, Baltimore's old cannon-ball works. My father recounted his mother's description of the business:

I used to make the soda; I had to work a hand pump to pump the gas into the water. Then we would serve the seltzer, supply a table and chairs, pay the rent and the light bill, and then I had to wash the glass. For that, I took in exactly one cent. When I did that a hundred times, when I washed a hundred glasses, I took in a dollar.

They learned to speak English, though not really to read or write it, but they spoke Yiddish at home and in the neighborhood. All their lives in America, they got their news from the Daily Forward, a Socialist Yiddish-language newspaper published in New York. They were not Socialists, however; my grandmother's politics were rooted entirely in neighborhood organizations, primarily women's clubs and loan circles, through which poor immigrants helped take care of each other; my grandfather, as a small businessman, understood government basically as a mob at City Hall extorting protection money in the form of taxes. For example, long after he had traded in his horse and wagon for a Chevrolet delivery van, he continued to pay his horse tax every year; he figured he was down in somebody's books for that amount.

They had five children who all grew up in Baltimore and lived there or nearby as adults. Then came sixteen grandchildren, who scattered across the country, from Maine to California. And then dozens of great-grandchildren.

This picture is the oldest family document we have; we have nothing from the old country, no names or stories or objects, with the possible exception of one battered copper pot. I remember thinking to myself when I was growing up that my family just didn't go back very far in time, just didn't have a history at all; in other families, there were ancestors back in the olden days, but the most ancient people I was related to were still alive, still in Baltimore, where that side of my family history seemed to have sprung to life.

Now, however, this is a really old photo, from a wedding more than a century ago. Rose and Charlie are gone, as are all five of their children, my father's generation. We in the cousins' generation are getting on in years now, and most of us don't keep in close touch with one another. But it's undeniable that the family goes way, way back before us.

And there's yet another generation now, Rose and Charlie's great-great grandchildren. Crazy, isn't it, how that keeps happening.

wedding

Baltimore

1905

immigrants

Rose and Charles Horowitz

Lithuania