Hole in the Clouds

Nov 13, 2010

The hand-held GPS unit hasn't really revolutionized twenty-first-century life, but the combination of GPS and internet has definitely generated some new recreational obsessions. There is geocaching, for example, in which people search for hidden treasure boxes using geographical coordinates they've downloaded from websites. And on a larger scale, there's confluence-bagging.

A confluence is a point where whole-number coordinates of latitude and longitude intersect--for example, 40 degrees north latitude at 75 degrees west longitude, the closest confluence to where I live. You bag a confluence by visiting it precisely, taking a picture of the numbers displayed on your GPS unit to prove you were really there. After a visit, if you upload the documentation to the

confluence.org website--including a narrative describing your trip and photos of the confluence site, of views in every direction from the point, and of interesting sights nearby--then the ether-world will have a digital record of your achievement. As of today, 11,782 visits to 5,957 confluence points have been documented in the website.

The confluence near my house--40 north, 75 west--is on a golf course fairway in New Jersey; it's easy to find and easy to get to, if the golf course people don't chase you away. Some confluences are more challenging to bag, especially in rough, remote, uninhabited country and in relatively roadless, high-conflict regions, such as East Timor.

Last summer, a team of three Russian confluence-baggers, who have documented visits to some 29 confluence points, devoted their vacation to bagging a few more in Siberia, near Lake Baikal. They visited two watery confluences on the lake itself, traveling 200 nautical miles by boat. Then they got back in their car and sought out the confluence at 52 north 108 east, in logged-over hills east of the lake, in the Siberian republic of Buryatia.

"Having reached the side road to Onokhoy-Shibir," they wrote, "we turned left and drove onto a dirt road headed to our goal.

"We passed a village and reached some road furcation. Guided by GPS arrow, we chose the left road along a creek. Soon the road turned into a clearing for the cable. We slowly dragged our wheels along it until we hit to a high fence." Time to park the car and start walking.

"We were unaware of the existence of a sports training camp, Druzhba (Friendship). The place where a stream flowed under a fence was a secret path on which the 'young pioneers' ran AWOL. We used the hospitality provided by the hole in the fence and got into the camp."

The precise confluence point, it turned out, was near the camp entrance, pictured here, easily accessible by road had they only chosen the correct fork. But by driving directly to the confluence instead of sneaking in like young pioneers returning from some unofficial adventure, "we would have lost the opportunity to plunge into the 1970s and 1980s and feel as the pioneers of those years."

Siberia

GPS

confluence

Lake Baikal

Young Pioneers

Buryatia

(Image credit: Evgeny Krivosudov)

May 2, 2012

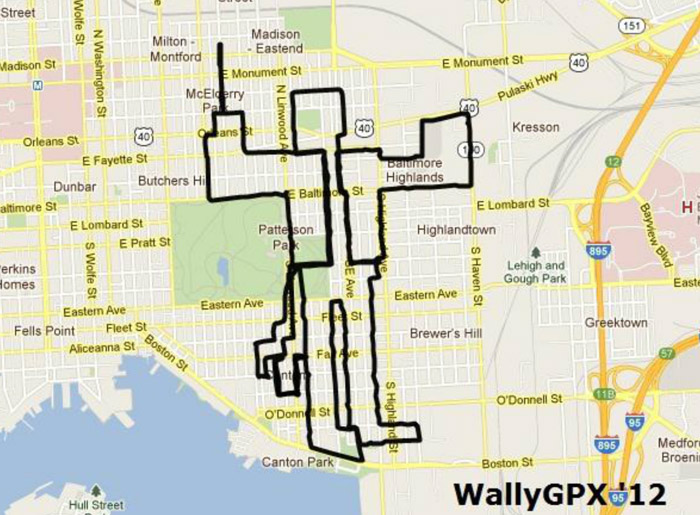

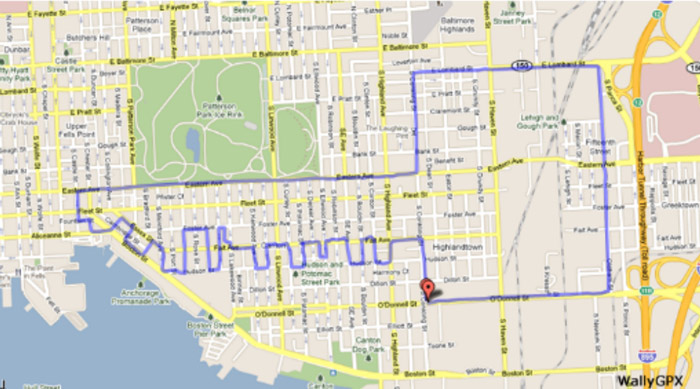

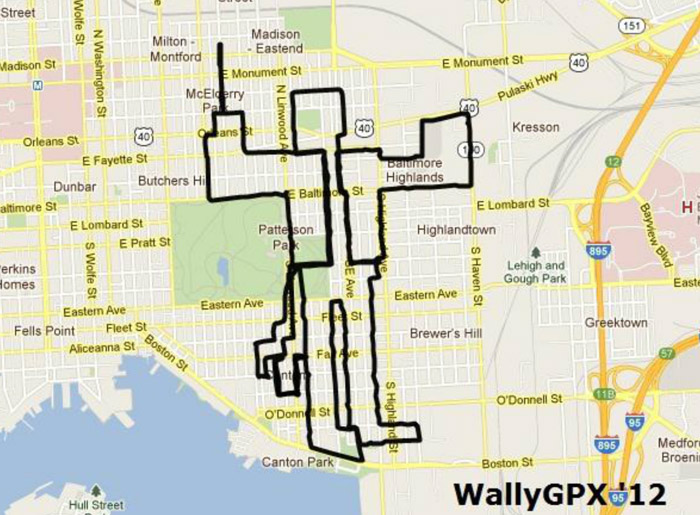

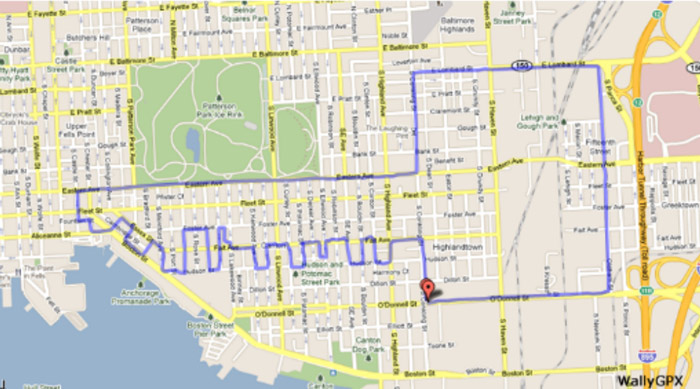

Here we see The Superconductor, a GPS track created a couple of months ago by Michael J. Wallace as he navigated his bicycle through the streets of Baltimore.

Here we see The Superconductor, a GPS track created a couple of months ago by Michael J. Wallace as he navigated his bicycle through the streets of Baltimore.

The track is invisible out on the street, of course; it comes to us as a digital recording (via a GPS app on a cellphone) of the exact path taken by Wallace's bicycle during one of his fitness rides. He designs a different track for each ride, planning it out ahead of time on maps and satellite imagery and then following the route as precisely as possible, even if he has to go the wrong way down a one-way street or retrace part of his path without moving over to the other side of the street.

"Once the recording begins," he says on his website, "a continuous pedal-powered line is created." The line becomes visible only when he gets back home after the ride and checks it out on his computer screen. It's a "virtual geoglyph," he says, painted in sweat on the "local canvas" of his neighborhood.

The geoglyph below, of a Baltimore icon, the Francis Scott key, required 6.25 miles of pedaling on a wretchedly muggy night last summer, when the temperature was 87 degrees. Wallace started the ride listening to Clash in his headphones but soon switched to the Rolling Stones. Tracing the key took 53 minutes and 17 seconds, and along the way he noticed four dead rats in the street and one dead bird.

When he got to the upper righthand corner of the key, the street he was following northward dead ended at the bottom of an embankment. "I had to muscle my bike up a steep hill to catch E. Lombard Street back towards downtown," he noted. "Sometimes that's how the road goes."

bicycle

Baltimore

GPS

Michael J. Wallace

invisible lines

maps