Hole in the Clouds

Feb 9, 2011

In 1942 in the Melrose Park Buick plant outside Chicago, "vital cogs in America's war machine"--that's Office of War Information talk for airplane-engine gears--are being inspected for defects. Dorothy Miller, at left, checks a vital cog with aid of a tiny flashlight in her right hand. Sylvia Dreiser, at right, thinks about whatever it is she's thinking about, which may not be cogs at all. I'd rather ride in an airplane powered by Dorothy's cogs.

In 1942 in the Melrose Park Buick plant outside Chicago, "vital cogs in America's war machine"--that's Office of War Information talk for airplane-engine gears--are being inspected for defects. Dorothy Miller, at left, checks a vital cog with aid of a tiny flashlight in her right hand. Sylvia Dreiser, at right, thinks about whatever it is she's thinking about, which may not be cogs at all. I'd rather ride in an airplane powered by Dorothy's cogs.

If you click on this photo to get the large version and look at it closely, you may be able to see that both women's hands are slathered in oil. In fact, you have to wonder how many times a day did that penlight squirt right out of Dorothy's slippery fingers. Also, for what it's worth, Dorothy is wearing a hairnet and Sylvia isn't.

work

Dorothy Miller

Sylvia Dreiser

Melrose Park Buick

World War II

(Image credit: Ann Rosener, Office of War Information, via Shorpy)

Nov 23, 2011

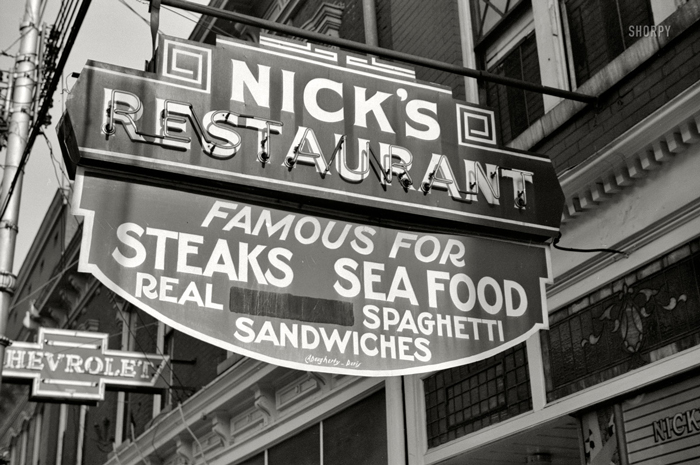

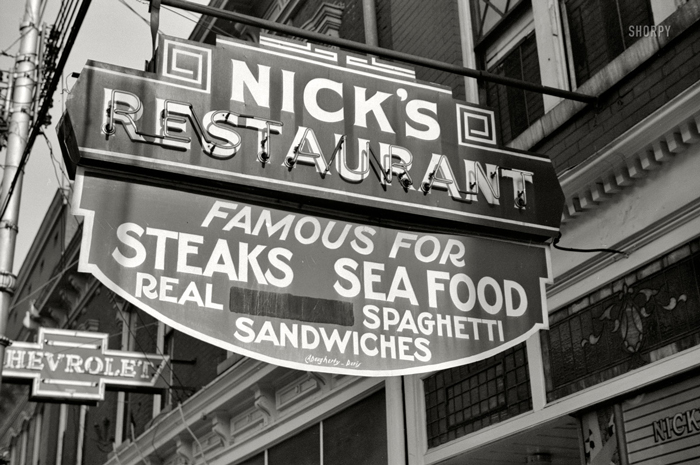

In 1940, Nick chose to black out one word on the sign in front of his Greek restaurant in Paris, Kentucky, the word that came between "real" and "spaghetti." Mussolini's Fascist regime had just invaded Greece, and the now-missing word, of course, must have been "Italian."

In 1940, Nick chose to black out one word on the sign in front of his Greek restaurant in Paris, Kentucky, the word that came between "real" and "spaghetti." Mussolini's Fascist regime had just invaded Greece, and the now-missing word, of course, must have been "Italian."

streetscape

politics

World War II

signage

Paris, Kentucky

1940

(Image credit: John Vachon, Farm Security Administration)

Apr 5, 2012

In February 1943, this unnamed woman was at work in the Vultree aircraft plant in Nashville, Tennessee, building a Vengeance Dive-Bomber.

In February 1943, this unnamed woman was at work in the Vultree aircraft plant in Nashville, Tennessee, building a Vengeance Dive-Bomber.

Among the hundreds of thousands of photos commissioned by the government in the 1930s and early 1940s to document economic-recovery programs and the war effort, only a handful, including this one, were in color. After three-quarters of a century, the color images seem to suggest a world that is much more familiar to us today, much less shadowy and distant than the shades-of-gray America that is portrayed so dramatically in the more famous black and white works of the era.

Aircraft parts–fuselage panels, wings, and doors–are still manufactured today at the Vultree site in Nashville, which is now operated as part of the Vought subdivision of Triumph Aerostructures.

Nashville

Tennessee

work

World War II

aircraft

(Image credit: Alfred T. Palmer)

Apr 17, 2012

Another sample from the Library of Congress's small collection of color photos from the 1930s and 1940s, this one shows a woman working with aerial photos to develop camouflaging for airfields and critical factories during World War II.

Another sample from the Library of Congress's small collection of color photos from the 1930s and 1940s, this one shows a woman working with aerial photos to develop camouflaging for airfields and critical factories during World War II.

Camouflage experts at New York University would use the aerial photos to build a model of an area that included the facility to be camouflaged. Then they would paint over the facility on the model until it blended in with its surroundings. Aircraft plants on the West Coast were covered with acres of canvas and plywood painted and sculpted to resemble suburban subdivisions. Airstrips were painted to look like small-town streets and farmland from the air.

Not everything was so easy to camouflage; ships at sea, for example, proved impossible to hide no matter how they were painted. A completely different approach, known as dazzle camouflage, was devised for ships; they were painted with crazy stripes at jagged angles, visible from afar but very different to interpret as to size, direction, and speed of movement.

Some fighter planes were painted pale pink, a color that was thought to show up as white or grayish, like clouds, at high angles of intense sunlight.

This photo looks posed, and the woman may be a model rather than a serious camouflage authority; she is holding the aerial photo more or less upside down with respect to the model she's supposedly painting.

art

World War II

1942

camouflage

New York University

(Image credit: Office of War Information)

Sep 22, 2013

By the summer of 1942, the American war effort was in such high gear that many agricultural regions were experiencing a severe labor shortage. All the young men were serving in the military, almost everybody else was working in war industries, and nobody was left to pick the nation's peas and beans.

By the summer of 1942, the American war effort was in such high gear that many agricultural regions were experiencing a severe labor shortage. All the young men were serving in the military, almost everybody else was working in war industries, and nobody was left to pick the nation's peas and beans.

As part of a program designated "Food for Victory," this specially chartered train brought more than three hundred high school boys and girls from the coal-mining town of Richwood, West Virginia, to the farming district around Batavia in upstate New York, where they would pick peaches, apples, tomatoes, and other crops. The program also brought in teenagers from other non-farming places, including Brooklyn, New York, where one of the high schoolers who signed on to help with the harvest upstate was the young Helen Ruskin, Norman's mother.

New York

West Virginia

Helen

train

World War II

high school

1942

youth

Richwood

(Image credit: John Collier via Shorpy)

Jul 15, 2012

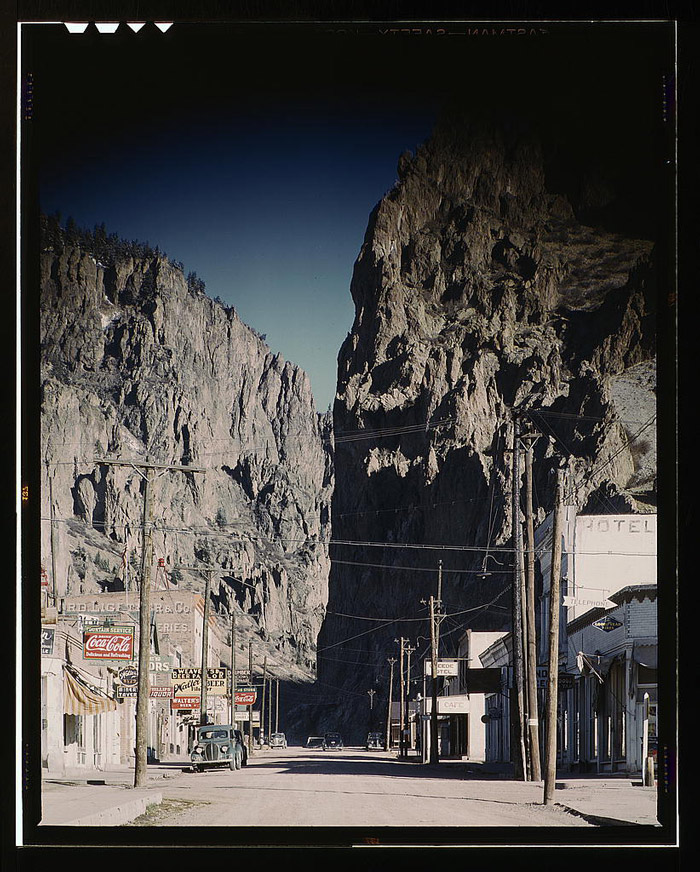

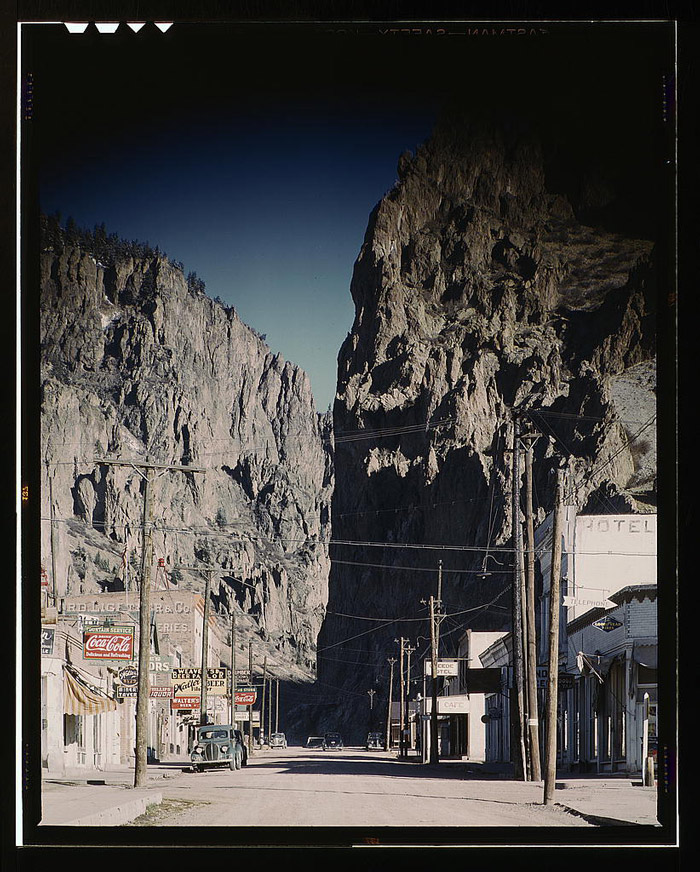

The main street of Creede, Colorado, led to the mouth of an important lead and zinc mine in 1942, when the picture above--part of a small series of color photos commissioned by government agencies in the 1930s and 1940s--was taken for the Office of War Information. The mine remained active until 1985 and has recently been reopened; in fact, it is currently advertising for mechanics to troubleshoot and maintain lead mining equipment.

The main street of Creede, Colorado, led to the mouth of an important lead and zinc mine in 1942, when the picture above--part of a small series of color photos commissioned by government agencies in the 1930s and 1940s--was taken for the Office of War Information. The mine remained active until 1985 and has recently been reopened; in fact, it is currently advertising for mechanics to troubleshoot and maintain lead mining equipment.

Back in the late nineteenth century, silver was extracted from Creede ore, and more than ten thousand people crowded into the area. But ever since the silver panic of 1897, local mines have produced mostly lead, and fewer than a thousand people have lived here; the 2010 census counted 290.

A Western based on the Lone Ranger story and starring Johnny Depp will feature scenes shot in and around Creede. It is set for release in 2013.

Below is Creede's Main Street as it looked in 2005.

streetscape

World War II

1942

mine

Colorado

Office of War Information

Creede

(Image credit: Andreas Feininger)

Dec 13, 2012

During World War II, service flags like the ones hanging in these windows, could be seen in houses all over America. Within the red border of the window-hanging was sewn a blue star for each family member serving in the military. Gold stars acknowledged those killed in action.

During World War II, service flags like the ones hanging in these windows, could be seen in houses all over America. Within the red border of the window-hanging was sewn a blue star for each family member serving in the military. Gold stars acknowledged those killed in action.

The steps these children were playing on in 1942, along N Street SW in Washington, DC, were bulldozed a dozen or so years later as part of one of the country's largest "urban renewal" projects. All the residential and commercial neighborhoods in the city south of the national mall were condemned and all the residents evicted. The buildings were torn down and even much of the street grid scraped away, as a team of builders and designers led by I.M. Pei sought to start over from scratch, to create a 1950s-style urban utopia.

Before the urban renewal, Southwest Washington had been home to several generations of European immigrants and African American migrants from the South. Irish, Italian and Eastern European immigrants, possibly including these families, lived in the neighborhood west of Fourth Street SW, which was then known as Four and a Half Street. The street addresses here would have been very near Four and a Half Street. East of that street, mostly in more decrepit houses, lived African Americans, some of whom had come to Washington as freed slaves before or soon after the Civil War. The two adjacent neighborhoods both produced musical stars in the twentieth century: Marvin Gaye and Al Jolson.

Urban renewal wiped away all the homes, schools, stores, and other buildings except for one church, a fish wharf, and Bolling Air Force Base. A freeway was built through the middle of the new emptiness, with office complexes and new apartment buildings on either side. The project went the way of much mid-century city planning: people did come to work in the office buildings but went home every night as soon as they could, and people did live in the apartments but got in their cars and drove away to shop, play, and generally live their lives. Except at rush hour, neighborhood streets were empty.

It took another half-century, until 2003, before Southwest Washington got its first real grocery store. There has been something of a revival in recent years, as new stores opened and area parks were developed, giving people a reason to go outside and walk around. New apartment and condo projects have increased neighborhood density.

What happened to the thousands of people who were expelled from Southwest in the 1950s, possibly including the people in this picture? I'm not aware that anyone has kept track of them. Not to belittle their fate, but in one way or another, what happened to them happened to millions of Americans throughout the last century. In America, city people rarely stay put in the same neighborhoods generation after generation. People change and seek out different kinds of neighborhoods, and/or the neighborhoods change, pushing people out or leaving them uncomfortable and precariously clinging to homes in places that aren't what they used to be.

children

Washington, D.C.

streetscape

World War II

service stars

rowhouses

(Image credit: Louise Rosskam)

Mar 23, 2013

By 7 a.m. on June 21, 1942, the line of cars at this Texaco station, and at pretty much every gas station in America, spilled out of the lot and on down the street. Strict gas rationing to conserve fuel for the war effort was set to begin the next day, June 22, 1942.

By 7 a.m. on June 21, 1942, the line of cars at this Texaco station, and at pretty much every gas station in America, spilled out of the lot and on down the street. Strict gas rationing to conserve fuel for the war effort was set to begin the next day, June 22, 1942.

Note the corn plants growing in the grassy spot in the lower left corner of the picture. Note also the car closest to the camera: a brand new 1942 Packard.

McDowell's Texaco was in the 5200 block of Wisconsin Avenue NW, near Friendship Heights at the edge of Washington, D.C; a parking garage now occupies the spot.

Washington

cityscape

cars

World War II

District of Columbia

1942

5252 Wisconsin Ave NW

(Image credit: Marjory Collins for Office of War Information)

Jun 24, 2013

There has been a bridge here over the River Meuse in the Belgian town of Dinant since the twelfth century. In World War I, Charles de Gaulle was wounded during a battle for control of this crossing, but the bridge survived intact. It was destroyed, as shown here, in May 1940, when the retreating Belgian army blew it up behind them; the Germans, however, had already established a pontoon bridge nearby and were not delayed. It was rebuilt in 1950 and named for de Gaulle.

There has been a bridge here over the River Meuse in the Belgian town of Dinant since the twelfth century. In World War I, Charles de Gaulle was wounded during a battle for control of this crossing, but the bridge survived intact. It was destroyed, as shown here, in May 1940, when the retreating Belgian army blew it up behind them; the Germans, however, had already established a pontoon bridge nearby and were not delayed. It was rebuilt in 1950 and named for de Gaulle.

landscape

Belgium

World War II

village

Dinant

River Meuse

(h/t: Toefee via Shorpy)

Nov 1, 2013

Between 1941 and 1945, more ships were built here at Baltimore's Bethlehem-Fairfield yard than anywhere else on earth. Early in the war, building a Liberty Ship–a clunky freighter using a simple design left over from World War I–took eight months; by 1944, after they'd knocked out a few hundred Liberty Ships and gotten a knack for the work, Baltimoreans could build one in 19 days.

Between 1941 and 1945, more ships were built here at Baltimore's Bethlehem-Fairfield yard than anywhere else on earth. Early in the war, building a Liberty Ship–a clunky freighter using a simple design left over from World War I–took eight months; by 1944, after they'd knocked out a few hundred Liberty Ships and gotten a knack for the work, Baltimoreans could build one in 19 days.

Liberty Ships were slow, awkward cargo vessels intended to last only five years–just long enough, it was hoped, for them to supply our forces overseas with everything needed to win the war: jeeps, tanks, food, ammunition, mail from home, medical supplies. More than 2700 were eventually constructed, all from standardized designs and prefabricated components, at shipyards around the country; 350 were built here in Baltimore, more than in any other single yard.

They weren't pretty–the newspapers called them "Ugly Ducklings"–but they could float.

Next door to the Bethlehem-Fairfield works was another shipyard, Maryland Drydock, where round the clock war work was also under way. At Maryland Drydock, old freighters and passenger liners were refitted to carry troops to war. Racks of bunks were installed in former cargo holds and staterooms, stacked eight deep, with just 18 vertical inches between them. Thousands of soldiers would be crammed into each ship.

Meanwhile, thousands of workmen, including my father, were making fabulous wages of a whole dollar an hour at Maryland Drydock. My father worked as a sheet metal helper there until he got drafted into the army in 1943. His job was to install ductwork in hopes of providing ventilation deep into the holds of cargo ships, where once piles of sugar or bolts of cloth or cases of rum had traveled in relatively airless comfort. The idea was that soldiers on their way to war might want to be able to breathe while jammed together into the new bunks.

By the summer of 1944, my father couldn't have been very surprised when he became a passenger on a troop ship just like the ones he'd worked on at Maryland Drydock. Fifty years later, he wrote about his experience aboard the USS West Point:

As we boarded the ship, each of us was given a paper tag–mine was pink–and that meant I got into the chow line at 2 p.m. and 10 p.m. The cooks started serving Spam and beans as we pulled out of Boston harbor, and they didn't stop, around the clock, until our ship tied up at Liverpool four and a half days later.

On the ship, which was carrying more than 11,000 soldiers and a 1500-man crew, my company was assigned to bunks in the lowest hold. I was given a wooden club, and in the event of an emergency I was supposed to stand at the head of a specified gangway and maintain order.

We all ignored those assignments and simply slept on deck. We didn't want to be below the waterline when the torpedo struck. We lucked out.

Baltimore

World War II

Robert Horowitz

Liberty Ships

troop transport

Maryland Drydock

Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyard

(Image credit: Arthur Siegel for Office of War Information, via Shorpy)

Nov 11, 2013

Veterans' Day is Armistice Day, except that it's not. Calendar-wise, they're the same, but pausing or parading to show gratitude for our veterans is not really the same as pausing to commemorate the moment 95 years ago when soldiers lay down their weapons and those among them who still had the vitality and the nerve climbed out of their trenches and tried to put World War I behind them.

Veterans' Day is Armistice Day, except that it's not. Calendar-wise, they're the same, but pausing or parading to show gratitude for our veterans is not really the same as pausing to commemorate the moment 95 years ago when soldiers lay down their weapons and those among them who still had the vitality and the nerve climbed out of their trenches and tried to put World War I behind them.

We know more than a few military men and women who squirm at hearing "Thank you for your service," which servicepeople hear all the time these days. All too often, what the people who say it really mean by it is: "Hey, I'm not one of those dirty hippies who burned their draft cards and stuff during Vietnam–I'm a real American, and here's my business card." Or something like that.

Still. We are grateful for our veterans and for all the people through the years who put their lives on the line for us. People sacrificed so much in so many wars, and way too many of those who benefited from their sacrifice are obnoxious Americans like me.

Anyways, VJ Day, much like Armistice Day, was a very good day for hundreds of millions of people around the world. We young folk know it mostly from Eistanstadt's iconic photo of a kiss in Times Square, recreated here in Lego by photographer Mike Stimpson.

New York

World War II

World War I

Vietnam

Alfred Eisenstadt

military

Lego

Times Square

Veterans Day

(Image credit: Mike Stimpson via mikestimpson.com)

Apr 26, 2014

Some of the middle school students participating in their class field trip to the battleship USS Missouri in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, appear enthusiastically prepared to answer their teacher's question. Of course the question might be: Who's ready for lunch?

Some of the middle school students participating in their class field trip to the battleship USS Missouri in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, appear enthusiastically prepared to answer their teacher's question. Of course the question might be: Who's ready for lunch?

The students are seated in one of several mess halls deep in the ship; several ladders above them is the deck where the Japanese surrendered on September 2, 1945, to Gen. Douglas MacArthur and representatives of all the Allied powers, finally ending World War II. The American flag flown that day at the ceremony had only 31 stars and was hung backwards, stars at upper right; it was the original flag brought to Tokyo by Admiral Perry in 1853 when Japan was first opened to international trade, and it had frayed so badly over the years that one side of it–the right side–was sewed over with a protective linen covering, leaving only the reverse side for display.

Just below the deck where the ceremony took place is a dented spot in the hull. Six months before the surrender, during the bombardment of Okinawa, a kamikaze pilot had crashed into the Missouri, losing a wing off his plane and starting a gasoline fire aboard ship. The fire was quickly put out, and the ship was only dinged, not seriously damaged; the pilot, however, did not survive. The story is that the Missouri's captain, William Callaghan, had to rescue the pilot's corpse from sailors attempting to summarily dispose of it; Captain Callahan insisted on a full funeral service for the pilot, with military honors and burial at sea. The dent in the hull was never repaired.

After World War II, President Truman decommissioned every other battleship in the navy but insisted on maintaining the Missouri in active service, over the objections of military advisors. Battleships had no role to play in postwar navy planning. The Missouri was sent to Korea, however, during that conflict. It was then mothballed–but returned to duty one last time in 1984 during President Reagan's military buildup. It provided artillery support during the First Gulf War before being finally deactivated.

Since 1998, the Missouri has been a major tourist attraction at Pearl Harbor, as well as a school field trip destination. And there's plenty on board for the schoolchildren to see: big guns, tall stacks of bunks, signs insisting on short showers while at sea, and, of course, the backwards flag and the dent in the hull.

Up top, on deck underneath some of those big guns, a few members of the Marine Band entertained the tourists. The day we and the middle schoolers visited, the band played "Jingle Bell Rock," but now that it's springtime, the setlist has probably changed.

middle school

children

World War II

ship

field trip

USS Missouri

Pearl Harbor

Hawaii

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Mar 1, 2016

In January 1943, Australian truck gardener and food packager Edgell & Sons Ltd opened a new cannery in Cowra, New South Wales, for the war effort; by January 1944, these women and other employees working in shifts around the clock had shipped off one million cans of tomatoes and other vegetables.

In January 1943, Australian truck gardener and food packager Edgell & Sons Ltd opened a new cannery in Cowra, New South Wales, for the war effort; by January 1944, these women and other employees working in shifts around the clock had shipped off one million cans of tomatoes and other vegetables.

The cannery at Cowra stayed in operation till 2013, by which time Edgell had shifted over mostly to frozen foods, and every other cannery in Australia had already closed down. Birdseye now owns the company, though Edgell survives as a brand for the Australian market.

food

work

World War II

Australia

industry

factory

women

New South Wales

Cowra

1943

(Image credit: Office of War Information via Shorpy)

Jan 25, 2017

Notes from the Office of War Information, December 1943: "In the evening, Hugh Massman and his wife fold diapers. Joey's bureau drawer crib is moved to the side of their bed for the night."

Notes from the Office of War Information, December 1943: "In the evening, Hugh Massman and his wife fold diapers. Joey's bureau drawer crib is moved to the side of their bed for the night."

The Massman family lived in Washington in 1943 while Hugh, a petty officer in the navy, attended a specialized training program. Photographer Esther Bubley spent a few days with them for a feature story about military family life.

After the war, the family returned home to Montana, where they had seven more children.

Washington, DC

baby

World War II

1943

Hugh, Lynn, and Joey Massman

home front

(Image credit: Esther Bubley, via Shorpy)

Feb 9, 2018

"Enlisting in the Marines," reads the caption from December 1941." Recruiting office. San Francisco, California.".Photo: John Collier / Courtesy / FSA-OWI Collection / Library Of Congress

San Francisco

World War II

1941

military

enlisting

double-breasted suits

Marines

fedoras

(Image credit: John Collier for OWI)

In 1942 in the Melrose Park Buick plant outside Chicago, "vital cogs in America's war machine"--that's Office of War Information talk for airplane-engine gears--are being inspected for defects. Dorothy Miller, at left, checks a vital cog with aid of a tiny flashlight in her right hand. Sylvia Dreiser, at right, thinks about whatever it is she's thinking about, which may not be cogs at all. I'd rather ride in an airplane powered by Dorothy's cogs.

In 1942 in the Melrose Park Buick plant outside Chicago, "vital cogs in America's war machine"--that's Office of War Information talk for airplane-engine gears--are being inspected for defects. Dorothy Miller, at left, checks a vital cog with aid of a tiny flashlight in her right hand. Sylvia Dreiser, at right, thinks about whatever it is she's thinking about, which may not be cogs at all. I'd rather ride in an airplane powered by Dorothy's cogs.

Veterans' Day is Armistice Day, except that it's not. Calendar-wise, they're the same, but pausing or parading to show gratitude for our veterans is not really the same as pausing to commemorate the moment 95 years ago when soldiers lay down their weapons and those among them who still had the vitality and the nerve climbed out of their trenches and tried to put World War I behind them.

Veterans' Day is Armistice Day, except that it's not. Calendar-wise, they're the same, but pausing or parading to show gratitude for our veterans is not really the same as pausing to commemorate the moment 95 years ago when soldiers lay down their weapons and those among them who still had the vitality and the nerve climbed out of their trenches and tried to put World War I behind them.