Diving for deadheads

Nov 10, 2009

Old-school deadheads are logs that sank to the bottom of a river or lake during the logging drives of the last century or the century before that or even the century before that. Before the railroads reached the northwoods, loggers went out in the forests every winter, cut down the trees with axes or cross-cut saws, and dragged the logs down to the banks of the nearest river. Come spring, they would drive the logs downriver to saw mills or later paper mills.

The log drives were operated every spring in Maine from the 1770s until the mid-twentieth century, especially on the Penobscot River, which became the most important logging river in the world, transporting hundreds of millions of board feet of lumber every year to the mills in Bangor. When the Penobscot was high and water was running fast,, logs piled up in dangerous logjams. When water was low, the logs slowed and beached themselves on the rocks. Either way, inevitably, some logs became waterlogged and sank.

Down at the bottom, logs eventually lose their bark and become slimy, but the wood is perfectly preserved in cold water and can be dried out and used for anything. While millions of logs are streaming by on top of the water, it is not economical to salvage the deadheads at the bottom. Today, the economics are different.

If you want to cut standing timber on state-owned land, you have to pay the state about 40% of the estimated value of the lumber you will sell. If you want to salvage deadheads from a lake or river in Maine, you'll have to pay 20% of the lumber value. This year, two underwater logging operations tried to make a go of it in the state.

They use pontoon boats equipped with fish-finders, which have no trouble locating the logs. The guy working Moosehead Lake irigged up a mechanical deadhead retrieval system with grappling hooks and winches. The guy working the Penobscot River dives with scuba equipment to snag the logs for his winch. Either way, on a good day, they might bring up six or eight logs, lash them to the pontoons, and haul them to shore, where they'll eventually be carried by truck to a sawmill. The process is time-consuming, and it's not cheap, but the wood is of a quality that is no longer available in standing forests--old-growth lumber, sometimes two or three feet in diameter, with the close-packed growth rings reflecting slow centuries of maturation.

The ecological issues are tough. On the one hand, after decades or centuries underwater, the deadheads have developed a niche of their own in the riparian ecosystem, feeding insects with their bark and sheltering baby fish.. Also, the logs cannot be removed without stirring up a lot of sediment and disrupting all the critters in the water. On the other hand, the more salvaged lumber we use, the fewer new trees we'll have to cut.

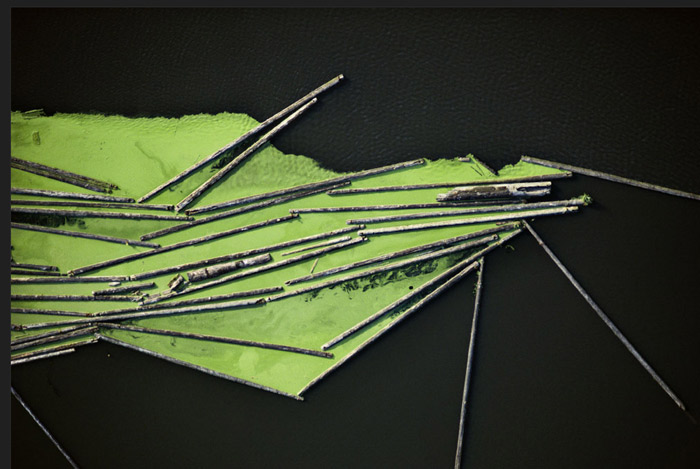

This picture is a still from a newsreel about diving for logs in the Penobscot.