In the Nepalese skies

Jan 4, 2010

This birdseye view of the town of Biratnagang, Nepal, was captured from ?????

Jan 4, 2010

This birdseye view of the town of Biratnagang, Nepal, was captured from ?????

Mar 1, 2011

It is obvious to some people that Nepal's Gorek Shep plateau--the world's highest sizeable plateau, abutting Everest Base Camp at 5,165 meters above sea level--is shaped exactly like London's famed international cricket ground, the Oval.

British mountaineer Richard Kirtley, for example, took one look at the Gorek Shep and concluded that it was so "perfectly cricket-field sized and shaped" that "the locals" must be using it as a pitch. He was wrong; nobody ever played cricket there, presumably because few people remember to bring their cricket gear along for nine extremely arduous days of trekking en route to Everest Base Camp.

But some people really like cricket. Kirtley organized a 50-man expedition that trekked to Gorek Shep in April 2009, cleared the pitch of rocks ("sometimes with pickaxes"), and contested the world's highest game of cricket, the Nokia Maps Everest Test. Team Hillary beat team Tenzing by 36 runs, with 6 balls remaining.

I wouldn't know a cricket pitch if it jumped up and bit me, and I am way too old and timid and out of shape to imagine venturing to Everest Base Camp. Still and all, I'm leaving for Nepal in a couple of days, and I'll be away from the computer and off trekking till the middle of March. It was my sister's idea, and also her frequent flyer miles. Details and pictures to come.

Be sweet while I'm away.

Mar 21, 2011

The guidebooks say that Nepal is a "quirky" place, where people use thousand-year-old statues to hold up their clotheslines. The guidebooks are right.

The guidebooks say that Nepal is a "quirky" place, where people use thousand-year-old statues to hold up their clotheslines. The guidebooks are right.

As this photo suggests, Nepalis use a confection of spit and wistfulness to hold up their electrical grid. It works about as well as you'd guess. In the capital city of three million people there is not a single functioning traffic light.

After spending four days knocking about in Kathmandu and another week trudging very slowly through the Himalayan foothills, I filled up my camera with curiosities and have of course become an expert on all things Nepalese. I've got stuff to share in upcoming G'mornin's. But the world has gone on spinning, so Kathmandu cannot always take priority. Glad to be back, hope everybody's well, look forward to hearing everybody's news.

Mar 22, 2011

WWBD? (What would Buddha do, in his tattoo studio?)

WWBD? (What would Buddha do, in his tattoo studio?)

Most Nepalis are Hindu, but we're told that their understanding of Hinduism is expansive enough to include the Buddha and his spiritual ways. Up and down the streets of Kathmandu are ornate, pagoda-style Hindu temples, little curbside chapels associated with one or several deities, modest "resting places" for the spirits of the departed, and big, bold Buddhist stupas like this one.

It is against the law to kill a cow, and cows do wander around town, especially out near the airport. But Nepalis have other cowlike animals--water buffalo and yak--that provide them with meat, milk, fiber, leather, and, um, horsepower, thus facilitating the religious exclusion of cows from these sorts of roles. Buffalo and yak look well-fed; the religiously venerated cows appear to be starving.

A substantial number of Nepali men, especially among the many who ride motorcycles, show a certain veneration for Western-style leather jackets, presumably made of cow leather. The tattoos, body piercings, and dreadlocks, however, are for tourists.

Mar 23, 2011

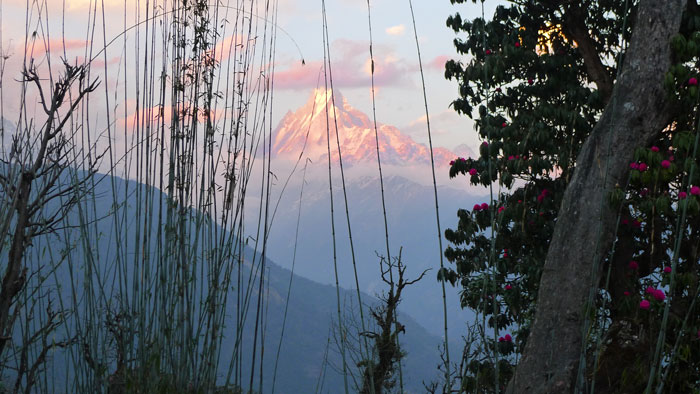

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.

But the scenic vistas were really the least of the experience. Nepali footpaths are essentially highways for the villagers who live in the hills; they have no railroads, no cars or trucks, certainly no airports, so if they want to order a little refrigerator from town and bring it home, somebody will have to walk up the trail with the refrigerator on his back.

If they want to bring a squawking chicken to a nearby village, somebody will have to tuck it under her arm and walk with it. If they want to bring in sacks of rice, or buckets of sheetrock, they will have to load up a donkey caravan and walk behind it with a loud voice and a big stick. They may have to walk for days and days and days, first on the floor of the valley, trudging upstream alongside a river, and then steeply up the side of the hill, on a rocky staircase of sorts built up over the centuries with rocks pried loose from the soil of terraced hillside fields and vegetable gardens.

One of these staircases had more than 4,000 steps–think four or five Empire State Buildings on top of one another. More of which to come.

The villages are agricultural in character, but they all have commerce now, thanks to the trekking trade. Restaurants feed the visitors, souvenir stands sell them stuff, and lodges put them up for the night–accommodations are "basic," with outdoor facilities, but tourists don't have to carry their own tents or food. To feed us trekkers, somebody from the village walked down the hill with an empty basket on his or her back and then walked back up again with a basket full of bottled water and other Western goodies. Nepalis don't use backpacks; they carry even the heaviest loads with the aid of straps across their foreheads.

At least one inn in every village is called Shangri-La. Rooms go for about 200 rupees–$3–a night.

Mar 24, 2011

Mar 25, 2011

There are two kinds of trekking in Nepal: teahouse trekking through populated countryside and tent trekking, which can venture into uninhabited mountain realms of rock and ice. Both kinds involve a group of tourists walking on trails for days or weeks, led by a guide and supported by porters.

There are two kinds of trekking in Nepal: teahouse trekking through populated countryside and tent trekking, which can venture into uninhabited mountain realms of rock and ice. Both kinds involve a group of tourists walking on trails for days or weeks, led by a guide and supported by porters.

The trekkers in the group usually carry only daypacks as they walk, containing bottled water, a fleece and rainjacket, toilet paper, and little more. Porters for teahouse treks carry duffels containing clothes and sleeping bags; for tent treks, they also carry food, camping gear, and perhaps mountaineering equipment. For a teahouse trek, there is one porter for every two or three trekkers in the group. For a tent trek, the ratio may be much higher.

Porters are ridiculously strong, fit, sturdy, reliable people. Most but not all are male, though they are not big men; some are barely five feet tall. They load up with 60 or 80 or even 100 pounds on their backs and oftimes finish the day's hike long before the lightly-laden trekkers. Many of them come from extremely remote villages, where subsistence farming is still the mainstay of life and there is little or no opportunity to earn cash income. Many porters, like most Nepalis, are illiterate. Work with the trekkers is seasonal and extremely irregular, and the pay is poor.

The two porters who accompanied our little group came from the Forbidden Kingdom of Mustang, high in the Himalayas near the Tibetan border. The provincial government of Mustang keeps the district almost closed to foreigners by charging so much for visas that only the wealthiest tourists can visit. Each year, as trekking season comes around, would-be porters in places like Mustang have to somehow come up with cash money--often borrowed--for bus fare to Kathmandu, where they gather in the airport parking lot to be looked over by trekking guides and perhaps chosen for work.

The guide for our group, Binaye, a Nepali who usually worked for a German tour company but who handled our trip on his own, went out to the airport to hire porters a few days before we were scheduled to arrive. He knew nothing about the two men he chose and had never met them before; he liked their attitude, he said, and they didn't smell of booze. From their homes in Mustang, they had walked four days to the bus stop and then ridden the bus for three days to Kathmandu, with no guarantee of work.

Both of them were among the pleasantest, hardest working people I've ever met.

After three days' trek, we reached the village of Ghorepani, a trekking hub. Many routes lead out from Ghorepani into the high Himalaya around Annapurna. The place bustled with trekkers coming and going, and over the years, trekking-related income had apparently led to public amenities not evident in smaller villages. Ghorepani had electricity and a medical clinic of some kind, and also a school.

Outside the school was a playground, a paved yard with a basketball goal and a volleyball net. Mule trains and horse caravans trooped across the back of the lot. Wastewater from a restaurant kitchen spilled in from the front.

As we settled into town to catch our breath and wait for dinner, porters were out in the playground playing volleyball. They had set down their loads, taken off their boots, and somehow found the energy to run and jump and dive and enjoy the late-afternoon sun.

Porters and trekkers eat separately and mostly have little communication or contact; per tradition, we come together for drinks the last night of the trip. That's when I learned that Beem, the porter with a hat and scarf and permanent smile, had five children, just like me.

Mar 28, 2011

There's a lot going on up on the rooftops around Kathmandu–clotheslines and gardens and solar water heaters and stovepipes and a lot of other stuff beyond my understanding.

There's a lot going on up on the rooftops around Kathmandu–clotheslines and gardens and solar water heaters and stovepipes and a lot of other stuff beyond my understanding.

This scene was in Bhaktapur, capital city of one of the three ancient kingdoms of the Kathmandu valley, about half an hour's drive from Kathmandu proper. Americans might understand Bhaktapur as a sort of Nepalese Williamsburg, where old buildings and crafts and cultural traditions are consciously preserved and displayed for tourists. No cars are permitted in town. However, Bhaktapur is about a thousand years older than Williamsburg, and it was no colonial outpost; for hundreds of years, it was the political and religious center of a wealthy royal court, with palaces and temples on a grand scale.

In the late eighteenth century, Bhaktapur lost out to an even wealthier kingdom in Kathmandu, and today the 30,000 townspeople get by on tourism and pottery-making; the pottery specialty seems to be wide, low bowls designed for culturing yogurt. An art school in Bhaktapur teaches ancient Buddhist thenka painting, and a paper factory follows traditional paper-making technology utilizing the inner bark of the lokta bush.

Below, in one of Bakhtapur's central squares, a woman walks past a Hindu temple guarded by a god with a mustache.

Mar 31, 2011

For at least the past fifteen hundred years, Swayambhunath Temple atop a high hill west of Kathmandu–the Monkey Temple–has been a holy site for Buddhists and Hindus both.

For at least the past fifteen hundred years, Swayambhunath Temple atop a high hill west of Kathmandu–the Monkey Temple–has been a holy site for Buddhists and Hindus both.

Hundreds of pilgrims climb the hill every morning before dawn (we're told), up a flight of more than three hundred steps to reach a temple plaza guarded by wooden lions. As the sun rises, the faithful start circling the huge white-domed stupa with its golden spire, spinning prayer wheels as they greet the dawn beneath Buddha's all-seeing painted eyes. Tibetan Buddhists circle the stupa clockwise; Nepali Buddhists go counter-clockwise. There are lots of both.

In addition to the stupa, the Monkey Temple complex features numerous shrines and temples, a monastery, and vendors selling everything from strawberries and tiger balm to postcards and mandalas.

One of the most popular shrines is to a Hindu deity, Heriti, the goddess of smallpox and childhood diseases. Apparently, Heriti is a fertility goddess who developed a niche specialty: keeping children alive till the age of twelve and curing smallpox even in adults. Because divine protection of this sort is much in demand but Buddhism lacked a deity with expertise, Heriti was borrowed from the Hindus. At her shrine, people bring flowers and gifts, both to enlist her aid and to thank her for good work. A donations box has been set up directly in front of her statue.

The whole hill does swarm with monkeys. People who live nearby complain that monkeys venture out into the neighborhood and eat everything green in people's gardens.

Apr 1, 2011

Apr 2, 2011

We were so tired, so slow, that nightfall caught us still trudging, trudging.

Apr 4, 2011

After walking three days uphill from the nearest road, my sister and me, we reached Ghorepani, which as you can see is just one little valley over from the sacred mountain called Fishtail. We'd started out in subtropical rice-and-banana-growing country and climbed up into just-barely-spring-with-patches-of-snow-and-ice country.

After walking three days uphill from the nearest road, my sister and me, we reached Ghorepani, which as you can see is just one little valley over from the sacred mountain called Fishtail. We'd started out in subtropical rice-and-banana-growing country and climbed up into just-barely-spring-with-patches-of-snow-and-ice country.

I am blessed with a sister who can make this sort of thing happen, who can move Himalayas if necessary to get stuff done. If the arrangements had been left up to me, I'd probably still be sitting at home fretting over the possible significance of Nepal's time zone (15 minutes ahead of India). I really, really lucked out in my choice of a sister.

Apr 7, 2011

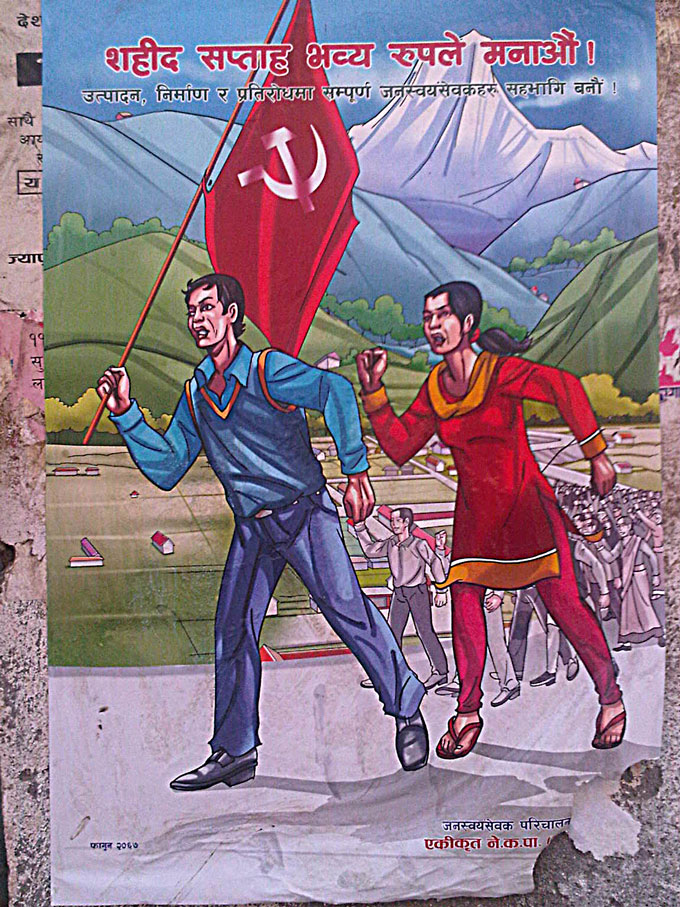

From my sister's collection of Kathmandu signs and posters:

The political poster reflects Nepal's very recent revolution, in which the king was overthrown for a parliamentary democracy. The leading party in parliament is the Maoists, but they didn't quite win a majority of seats; to govern, the Maoists had to form a coalition with the Marxist-Leninists. From what we heard, parliament wasn't doing much of anything and had repeatedly failed to write a constitution.

The political poster reflects Nepal's very recent revolution, in which the king was overthrown for a parliamentary democracy. The leading party in parliament is the Maoists, but they didn't quite win a majority of seats; to govern, the Maoists had to form a coalition with the Marxist-Leninists. From what we heard, parliament wasn't doing much of anything and had repeatedly failed to write a constitution.

Nepal's official communism does not seem to stop Nepalis from operating clearly capitalistic businesses, and the country is currently experiencing a heated real estate boom.

Apr 9, 2011

An apartment courtyard in central Kathmandu. The tent at lower right may be for a wedding.

An apartment courtyard in central Kathmandu. The tent at lower right may be for a wedding.

Apr 11, 2011

A billboard in a Nepali village along a popular trekking route hints at the animal life to be found in that part of the Himalayas. We saw pheasants and lemurs just as illustrated, but no leopards or sloth bears.

A billboard in a Nepali village along a popular trekking route hints at the animal life to be found in that part of the Himalayas. We saw pheasants and lemurs just as illustrated, but no leopards or sloth bears.

Missing from the billboard but definitely present in the underbrush: mongooses.

Apr 14, 2011

At 26,040 feet (8091 meters), the summit of Annapurna, tenth highest mountain in the world, is more than half a mile lower than the peak of Everest. Even so, Annapurna is the most dangerous mountain in the world to climb; only 153 climbers have ever made it to the top, and 58 have died trying.

At 26,040 feet (8091 meters), the summit of Annapurna, tenth highest mountain in the world, is more than half a mile lower than the peak of Everest. Even so, Annapurna is the most dangerous mountain in the world to climb; only 153 climbers have ever made it to the top, and 58 have died trying.

Annapurna is a huge massif with five major peaks. Here, at left above the village of Ghandruk and its green fields of millet, is Annapurna South, elevation 23,684 feet (7219 meters). The spur to its right, known as Himchati, just under 23,000 feet high, was first climbed in the 1960s, by a Peace Corps volunteer stationed in Nepal.

The name Annapurna is Sanskrit; a literal translation is "full of food," or "well-rounded." It is associated traditionally with the feminine form and with goddesses of the kitchen and the harvest, and more generally with Lakshmi, Hindu goddess of wealth.

The rightmost mountain in the picture above is Machhapuchhare–Fishtail–sacred to the god Shiva and off-limits to climbers. It has never been summitted.

The village Ghandruk is a day's walk uphill from the nearest road, including a climb up a staircase containing–if the trail sign is to be believed–more than 8,000 stone steps. My sister struggled diligently to keep count but could neither confirm nor disprove the official number. I was much too winded to try anything as complicated as counting; all I could do was huff and puff and sweat and whine.

Ghandruk is a village of Ghurkas, the renowned warriors. Military service has entitled some of the Ghurkas to emigrate to Britain or to work in such far-flung places as Singapore, and it is said that the village's main source of income is remittances from abroad. One man told us his son was working as a policeman in Singapore; he also told us that in Ghandruk his son went by the name "Big Sexy."

A day's walk uphill from Ghandruk is a village called Tadapani, where Annapurna seemed much bigger and closer (below). The solar water heater on the roof of our inn was working fine, but there were way too many of us hoping for hot showers. We saw solar heaters and panels all over Nepal, even in places where poles and wires brought in power from the grid.

Also, everywhere we went, even in Kathmandu with its three million inhabitants, the practice of "load sharing" shut down the electricity every few hours. We were told that outages were according to schedule and that a schedule for the coming week could be read in the newspaper, but we never saw a schedule and were always caught by surprise.

Apr 18, 2011

That's my sister's boot toe and walking stick probing for the next step as she prepares to work her way down a mountainside in Nepal.

That's my sister's boot toe and walking stick probing for the next step as she prepares to work her way down a mountainside in Nepal.

Nepali trekking trails, at least in the vegetated, more or less inhabited zones of the Himalayas, are mostly paved with stones, and the steep stretches are fashioned into endless rocky staircases. Donkeys can climb the staircases with ease, as can most Nepalis and probably even fit young Americans.

Building the staircases was part of the terracing project that has occupied Nepalese farmers for centuries. Rocks were pried up out of the soil and redeployed into retaining walls for thousands of tiny terraces, holding back the hillsides so that plows pulled by buffalo could work the land. Over the generations, as plows and hoes and hoofs and toes have continued to kick up rocks, farmers have built themselves stone houses and connected the houses to their fields with steep, stone-paved, stone-staircased trails.

Terraces and paved trails minimize soil erosion on steep slopes. Also, if the stones are cobbled together into stairsteps along the steepest stretches, the trails can head straight up and down without switchbacks, thus facilitating travel while minimizing the amount of land removed from cultivation.

On the other hand, straight up and down the stairs is . . . well, one elderly Nepali, who was scampering up the trail as we were struggling down, paused briefly to bless our knees.

One of the staircases we struggled up was said to contain more than 8,000 steps. My sister kept count, but irregularities in the size and shape of the steps led to uncertainty as to the exact number.

Every million billion steps or so there is a rest area, also built of stone, backed up by a stone wall with a low shelf. The shelf isn't actually low enough for sitting on, but it's about the right height for resting a backpack or other burden.

Below are three more pictures of stair-stepping in the Himalayas. The terraced fields look brown and barren, not because they have been abandoned but because we were traveling early in the springtime, before most crops had sprouted.

The last picture shows a rest stop in a village, with a trail that climbs onward and upward via the staircase at the extreme right of the scene.

May 6, 2011

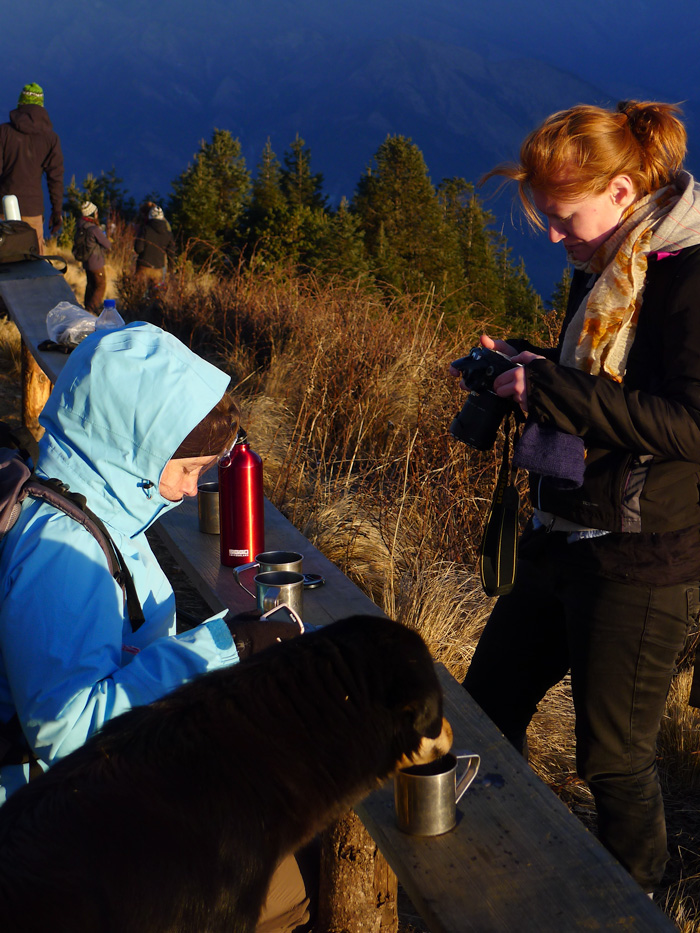

About a thousand feet straight up above the village of Ghorepani in Nepal's Annapurna region is the crest of Poon Hill, a vantage point where trekkers from around the world gather at dawn to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas.

About a thousand feet straight up above the village of Ghorepani in Nepal's Annapurna region is the crest of Poon Hill, a vantage point where trekkers from around the world gather at dawn to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas.

Poon Hill is 10,500 feet above sea level, and it's cold there at dawn. Well before dawn, enterprising citizens of Ghorepani make huge vats of hot tea and carry them up the trail to sell to the trekkers. Here, a local dog shares a trekker's cup of tea.

Dogs are ubiquitous in Nepal. In the countryside, most of them look just like this one–medium-sized, square-headed, with a thick black coat and light tan markings. In the city of Kathmandu, the dog population exhibits more variety, but they still tend to be medium-sized, square-headed, and thick-coated. Dogs can be seen sleeping in the sun on sidewalks and streets all over the city. They live off garbage and scraps tossed out the back of restaurants and homes. They show no aggression toward humans and only a little toward other dogs; none of them, of course, is on a leash. Mostly, they sleep.

May 8, 2011

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

Trekkers come from literally all over the globe to watch the sun rise over the Himalayas from the top of Poon Hill. And then, as soon as the sun is bright enough, they all take pictures of each other.

We met trekkers from the Netherlands, Australia, Israel, France, Japan, Ireland, Germany, and probably some other countries I've forgotten. The group in the foreground here was from China.

Very few came from the United States. Americans generally don't have the vacation time or the "hillwalking" tradition shared by the Europeans. However, patterns of tourism are changing; in the resort city of Pokhara, which we visited after our trek, we met a tour group of senior citizens from New Jersey.

Jun 24, 2011

These horses were attending to one another in the schoolyard in the village of Ghorepani. The roof on the schoolhouse, like all the other roofs in Ghorepani, is painted blue. A few kilometers back down the mountain, in the village of Ghandruk, all the roofs are painted white.

These horses were attending to one another in the schoolyard in the village of Ghorepani. The roof on the schoolhouse, like all the other roofs in Ghorepani, is painted blue. A few kilometers back down the mountain, in the village of Ghandruk, all the roofs are painted white.

Jun 25, 2011

One afternoon in Kathmandu, we saw the men and then the women and then the car, all dressed up with clearly some place special to go. A recent wedding we heard about had twelve hundred guests, but all we saw of this one was the procession on the street, complete with a marching band. The band looked and sounded just like a western marching band and is not pictured here.

One afternoon in Kathmandu, we saw the men and then the women and then the car, all dressed up with clearly some place special to go. A recent wedding we heard about had twelve hundred guests, but all we saw of this one was the procession on the street, complete with a marching band. The band looked and sounded just like a western marching band and is not pictured here.

Nepalis claim they have more official holidays than any other country on earth. They know how to party.

Jul 2, 2011

Like young'uns everywhere, children in Nepal like to play out front on the stoop.

Jul 5, 2011

People wearing AC/DC shirts like to visit temples in Bakhtapur Square just like everybody else.

Jul 6, 2011

The valleys and lowermost hillsides of Nepal are subtropical; the crops grown there include tea and coffee and these banana trees. If a sturdy trekker were determined to leave the subtropics behind, he or she could walk straight uphill from here into patches of spring snow in a few hours, and into the glacial icefields of the high Himalaya in a few days.

The valleys and lowermost hillsides of Nepal are subtropical; the crops grown there include tea and coffee and these banana trees. If a sturdy trekker were determined to leave the subtropics behind, he or she could walk straight uphill from here into patches of spring snow in a few hours, and into the glacial icefields of the high Himalaya in a few days.

Global warming is spreading up the mountainsides. Nepalis hope they have figured out a way to make money on climate change; the increasing heat in the air that has reduced productivity of tea plantations in India seems to have permitted tea cultivation higher than ever before on Nepalese hillsides. Not all the new plantings have thrived–the air is thinner in the high mountains, and the soil is rocky and poor. But fine tea is coming out of Nepal these days, from slopes about a mile higher than the bananas shown here.

In the long run, of course, tea won't save Nepal. As the glaciers shrivel in the high mountains and a scanty winter snowpack produces less and less spring runoff for the rivers of the subcontinent, people will have a hard time growing much of anything. Huge thirsty cities downstream are already beginning to compete for water with peasants struggling to irrigate the tiny terraces they have clawed into the mountainsides of Nepal.

Well. Maybe somebody will think of something.

Jul 10, 2011

Soccer is popular in Nepal, even if the fields are more dirt than grass, and this year the national team, known as the Ghorkalis, is on a roll. Last week, Nepal notched two victories, 2-0 and then 5-0, in 2014 World Cup qualifying matches against East Timor. The Ghorkalis have a new coach, Graham Roberts, an Englishman who played for Tottenham and Chelsea, mostly on defense, and won six caps for England.

Soccer is popular in Nepal, even if the fields are more dirt than grass, and this year the national team, known as the Ghorkalis, is on a roll. Last week, Nepal notched two victories, 2-0 and then 5-0, in 2014 World Cup qualifying matches against East Timor. The Ghorkalis have a new coach, Graham Roberts, an Englishman who played for Tottenham and Chelsea, mostly on defense, and won six caps for England.

Meanwhile, in league play, defending champions Nepal Police Club holds a comfortable lead in the Martyrs Memorial Red Bull Division A, though Yeti Air Himalayan Sherpas Club is not out of the running.

The field shown here is in the suburbs of Kathmandu, at the base of the hill topped by the Monkey Temple.

Aug 12, 2011

Very soon, if you go to Nepal, to the village of Ghandruk, you may be able to arrange to stay in this new inn, the Hotel Magnificent. It was almost complete, as you can see, when we were there this past March.

Very soon, if you go to Nepal, to the village of Ghandruk, you may be able to arrange to stay in this new inn, the Hotel Magnificent. It was almost complete, as you can see, when we were there this past March.

I have not been inside the Magnificent, but I can tell you what it is like because all the trekking hotels in the Annapurna region of Nepal are very nearly identical.

The rooms are cubicles separated from one another by partitions of particle board, sometimes unpainted, sometimes covered by a single coat of paint that has been so watered down you can read the ISO number stamped on the particle board right through the color. The beds are thin mats laid on wooden shelves--magnificently comfortable after a day on the trail.

There is a single lightbulb in the ceiling, and no other electrical outlets. Western tourists, of course, have brought along various electronic thingamajigs that need to be charged, but there's no way to take care of that in the bedrooms (unless you have invested in a kind of adapter we heard about, which screws into a light socket so your precious whatever could recharge itself while dangling down from the ceiling, and while you sit in the dark waiting to put the lightbulb back in its socket . . . ). Sometimes the people running the hotel will let you charge your stuff in the dining room, for a fee.

Also in your room is a window with a magnificent view.

There is a bathroom with a kind of fixture that is basically a hole in the floor There may be a sink for washing your face, either in the hallway or outside in a courtyard. Out back somewhere may or may not be a shed with a cold water shower. The water tap in the shower is labeled "USELESS;" we eventually figured out that the label was actually a directive to "USE LESS."

There is a restaurant, usually outdoors on a deck. The food is heavy and filling. Nepalis never order anything on the menu; they eat lentils for every meal.

There is no heat in the rooms. This was not a problem, since the porters had brought along our bags containing fleeces and coats and hats and gloves.

Some of the dining rooms are heated by a bucket of coals placed underneath the table. Blankets are pinned around the sides of the table, hanging down to the floor to keep the heat in. Stick your feet under the blanket. Scrunch up that blanket so your knees also are in the warmth. Magnificent.

One restaurant had a big woodstove in the middle, surrounded by a wooden railing. Nepalis pulled up benches so they could sit leaning forward, arms resting on the railing, holding mugs of steaming tea. Westerners wearing heavy coats sat at dining tables far off in the cold reaches of the room, near the windows, drinking lukewarm tea and talking about the magnificent view.

The new Hotel Magnificent is many hours' walk uphill from the nearest road. All the bricks, all the particle board, the tin for the roof, the buckets of blue paint–everything had to be carried uphill–up thousands of rock steps–strapped onto the backs of donkeys or humans.

And they only charge $2 or $3 a night. Pretty magnificent.

Aug 13, 2011

We saw several of these egg trees in Nepal; the eggshells are emptied out and then stuck on the ends of the tree branches. We never did learn what they are all about.

We saw several of these egg trees in Nepal; the eggshells are emptied out and then stuck on the ends of the tree branches. We never did learn what they are all about.

Sep 13, 2011

These ducklings are in Nepal, but they don't know that.

These ducklings are in Nepal, but they don't know that.

Apr 30, 2015

In the best of times, such as when this photo was taken about four years ago, repairing houses and other buildings in Nepal involved scaffolding made from stalks of bamboo lashed together.

In the best of times, such as when this photo was taken about four years ago, repairing houses and other buildings in Nepal involved scaffolding made from stalks of bamboo lashed together.

In the worst of times, such as right now, even this sort of construction work is an unimaginable luxury; all hands, and all hours of the day, are consumed by pawing through rubble, hoping or fearing to find relatives and friends and neighbors, and also hoping to find scraps of food and clothing and blankets, anything that might help the survivors cling to life.

There's nowhere to look for the basics of survival except in the rubble. There was no surplus of anything in Nepal to begin with, and only a single sizable airport for bringing relief in from the outside world.

Before these men could climb up on the scaffolding to lay brick, the sacks of mortar had to be brought in on the backs of people or donkeys; the streets here in this UNESCO World Heritage city of Bhaktapur, near Kathmandu, were much too narrow for cars or trucks.

Now even the country's best roads are ruined, and travel through the narrow lanes and paths is generally impossible. Some villages that used to be a day's walk or more from the nearest highway have not been heard from since the quake.

Bhaktapur was once a great royal court city; grand palaces and temples survived there for more than a thousand years. They're not there any more.