Hole in the Clouds

Mar 23, 2011

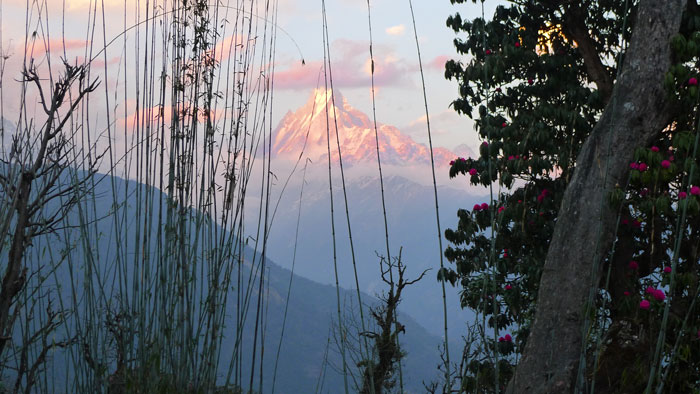

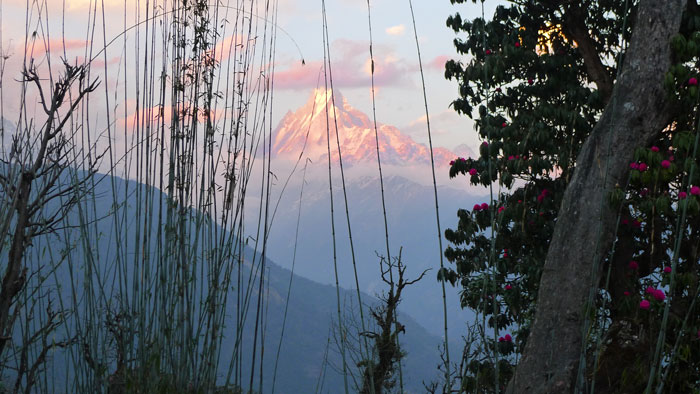

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.

But the scenic vistas were really the least of the experience. Nepali footpaths are essentially highways for the villagers who live in the hills; they have no railroads, no cars or trucks, certainly no airports, so if they want to order a little refrigerator from town and bring it home, somebody will have to walk up the trail with the refrigerator on his back.

If they want to bring a squawking chicken to a nearby village, somebody will have to tuck it under her arm and walk with it. If they want to bring in sacks of rice, or buckets of sheetrock, they will have to load up a donkey caravan and walk behind it with a loud voice and a big stick. They may have to walk for days and days and days, first on the floor of the valley, trudging upstream alongside a river, and then steeply up the side of the hill, on a rocky staircase of sorts built up over the centuries with rocks pried loose from the soil of terraced hillside fields and vegetable gardens.

One of these staircases had more than 4,000 steps–think four or five Empire State Buildings on top of one another. More of which to come.

The villages are agricultural in character, but they all have commerce now, thanks to the trekking trade. Restaurants feed the visitors, souvenir stands sell them stuff, and lodges put them up for the night–accommodations are "basic," with outdoor facilities, but tourists don't have to carry their own tents or food. To feed us trekkers, somebody from the village walked down the hill with an empty basket on his or her back and then walked back up again with a basket full of bottled water and other Western goodies. Nepalis don't use backpacks; they carry even the heaviest loads with the aid of straps across their foreheads.

At least one inn in every village is called Shangri-La. Rooms go for about 200 rupees–$3–a night.

landscape

mountains

flowers

Nepal

trekking

Ghorepani

Mar 25, 2011

There are two kinds of trekking in Nepal: teahouse trekking through populated countryside and tent trekking, which can venture into uninhabited mountain realms of rock and ice. Both kinds involve a group of tourists walking on trails for days or weeks, led by a guide and supported by porters.

There are two kinds of trekking in Nepal: teahouse trekking through populated countryside and tent trekking, which can venture into uninhabited mountain realms of rock and ice. Both kinds involve a group of tourists walking on trails for days or weeks, led by a guide and supported by porters.

The trekkers in the group usually carry only daypacks as they walk, containing bottled water, a fleece and rainjacket, toilet paper, and little more. Porters for teahouse treks carry duffels containing clothes and sleeping bags; for tent treks, they also carry food, camping gear, and perhaps mountaineering equipment. For a teahouse trek, there is one porter for every two or three trekkers in the group. For a tent trek, the ratio may be much higher.

Porters are ridiculously strong, fit, sturdy, reliable people. Most but not all are male, though they are not big men; some are barely five feet tall. They load up with 60 or 80 or even 100 pounds on their backs and oftimes finish the day's hike long before the lightly-laden trekkers. Many of them come from extremely remote villages, where subsistence farming is still the mainstay of life and there is little or no opportunity to earn cash income. Many porters, like most Nepalis, are illiterate. Work with the trekkers is seasonal and extremely irregular, and the pay is poor.

The two porters who accompanied our little group came from the Forbidden Kingdom of Mustang, high in the Himalayas near the Tibetan border. The provincial government of Mustang keeps the district almost closed to foreigners by charging so much for visas that only the wealthiest tourists can visit. Each year, as trekking season comes around, would-be porters in places like Mustang have to somehow come up with cash money--often borrowed--for bus fare to Kathmandu, where they gather in the airport parking lot to be looked over by trekking guides and perhaps chosen for work.

The guide for our group, Binaye, a Nepali who usually worked for a German tour company but who handled our trip on his own, went out to the airport to hire porters a few days before we were scheduled to arrive. He knew nothing about the two men he chose and had never met them before; he liked their attitude, he said, and they didn't smell of booze. From their homes in Mustang, they had walked four days to the bus stop and then ridden the bus for three days to Kathmandu, with no guarantee of work.

Both of them were among the pleasantest, hardest working people I've ever met.

After three days' trek, we reached the village of Ghorepani, a trekking hub. Many routes lead out from Ghorepani into the high Himalaya around Annapurna. The place bustled with trekkers coming and going, and over the years, trekking-related income had apparently led to public amenities not evident in smaller villages. Ghorepani had electricity and a medical clinic of some kind, and also a school.

Outside the school was a playground, a paved yard with a basketball goal and a volleyball net. Mule trains and horse caravans trooped across the back of the lot. Wastewater from a restaurant kitchen spilled in from the front.

As we settled into town to catch our breath and wait for dinner, porters were out in the playground playing volleyball. They had set down their loads, taken off their boots, and somehow found the energy to run and jump and dive and enjoy the late-afternoon sun.

Porters and trekkers eat separately and mostly have little communication or contact; per tradition, we come together for drinks the last night of the trip. That's when I learned that Beem, the porter with a hat and scarf and permanent smile, had five children, just like me.

sports

Nepal

work

trekking

Ghorepani

Beem

volleyball

porters

Apr 4, 2011

After walking three days uphill from the nearest road, my sister and me, we reached Ghorepani, which as you can see is just one little valley over from the sacred mountain called Fishtail. We'd started out in subtropical rice-and-banana-growing country and climbed up into just-barely-spring-with-patches-of-snow-and-ice country.

After walking three days uphill from the nearest road, my sister and me, we reached Ghorepani, which as you can see is just one little valley over from the sacred mountain called Fishtail. We'd started out in subtropical rice-and-banana-growing country and climbed up into just-barely-spring-with-patches-of-snow-and-ice country.

I am blessed with a sister who can make this sort of thing happen, who can move Himalayas if necessary to get stuff done. If the arrangements had been left up to me, I'd probably still be sitting at home fretting over the possible significance of Nepal's time zone (15 minutes ahead of India). I really, really lucked out in my choice of a sister.

landscape

mountains

Nepal

Ghorepani

Ellen

Himalayas

Carol

Fishtail

Jun 24, 2011

These horses were attending to one another in the schoolyard in the village of Ghorepani. The roof on the schoolhouse, like all the other roofs in Ghorepani, is painted blue. A few kilometers back down the mountain, in the village of Ghandruk, all the roofs are painted white.

These horses were attending to one another in the schoolyard in the village of Ghorepani. The roof on the schoolhouse, like all the other roofs in Ghorepani, is painted blue. A few kilometers back down the mountain, in the village of Ghandruk, all the roofs are painted white.

animals

Nepal

horses

Ghorepani

aw

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.

I had hoped that our days on the trail in the Himalayan foothills would include views like this, and such expectations were fulfilled many times over. This is Machhapuchhre–Fishtail–a holy mountain that no one is allowed to climb. The flowering tree is a rhododendron, Nepal's national flower, which was just coming into bloom in early March.