Fish story

Aug 21, 2009

Ever since last week, the Susquehanna River's been missing a big fish. Just kidding--he threw it back. Allen says this small-mouth bass is 19 inches long and weighs about four and a half pounds.

Aug 21, 2009

Ever since last week, the Susquehanna River's been missing a big fish. Just kidding--he threw it back. Allen says this small-mouth bass is 19 inches long and weighs about four and a half pounds.

Oct 17, 2009

There's an urban legend about a deer more spectacular than any other, a deer that's pure white, maybe even albino. It is glimpsed from time to time, usually at dusk or dawn or even after dark. It's shy and quick, won't stick around for the camera.

For a hunter to shoot such a deer, a white ghost of a deer, would make the whole forest cry. It would bring a whole lifetime of bad luck to the hunter who felled it. Unless it was actually a good luck charm. Or a trophy like no other--a trophy deer above all others.

One problem with the white deer, urban-legend-wise, is that there's widespread disagreement concerning what it might signify, if it signifies anything. The story is messy, if there is a story to it. But that's okay, urban-legend-wise, because the white deer is real--an estimated 1 deer out of 30,000 is albino, completely white with pink eyes.

Their coloration leaves them especially vulnerable to human hunters and other predators. Do they know that? Is that why they are so shy? Perhaps not, but their light-sensitive eyes may make them avoid daylight even more than other deer.

Nonetheless, Janet Goldwater sort of got a photo of an albino deer that had been eating apples from her tree in Eagles Mere, Pennsylvania. "This photo was taken (in a rush obviously!) through the window of my house," she writes. "My opportunity to take a photo came at dusk, hence the slow shutter speed."

Here, the albino deer looks almost like a unicorn, which seems appropriate enough. If you want clearer pictures, you can find them on the tubes. But this shot seems to pretty much sum up the whole white-deer thing: whatever is out there is hard to see, impossible to pin down, fleeing fast , but definitely, positively, really something.

Nov 28, 2009

Jack Delano's 1940 photo of Pittsburgh has a cinematic feel to it, as the lady on the staircase descends into a dark and cold and spectacular kind of hell. That particular hell--with sulfurous fumes belching from roaring steel mills--went south a generation ago, abandoning western Pennsylvania to rust and poverty. Somewhat remarkably, the city has stirred from its decline and reinvented itself as a clean and shiny, almost high-tech sort of place. But all along, the sons and daughters of Pittsburgh have been growing up into American image-makers, people who have shown us what we look like, or would like to look like, or hope to God we never ever look like. Fred Rogers, with his sweater and sneakers and perfectly detailed little world of children's TV--wasn't Pittsburgh's first or last cultural chronicler.

Early on, there was Stephen Foster, of Swannee River and Camptown Races fame, and then the painter Mary Cassatt, the modernist Gertrude Stein, and the Tarzan, Johnny Weissmuller. Some of the Pittsburghers have worked right up to the cultural edge--Andy Warhol--and some have walked us up to the brink, where we could glimpse a frightening future--Rachel Carson.

Most notable, perhaps, were all the guys who played football, generation upon generation of Pittsburghers who were big and tough and fast and focused: Johnny Unitas, Joe Namath, Mike Ditka, Larry Brown, Nick Saban, and way too many others

Then there were those who worked the cultural currents of the times: e.g., Bobby Vinton, Lou Christie, Charles Bronson. And the ones who have risen above their times, soaring elegantly: Gene Kelly.

But who took the neighborhood in this picture and warped it into a dark corner of the American consciousness? Back in the early days of television, Fred Rogers hired an imaginative young assistant who moved on to Hollywood and directorial fame and fortune--guy by the name of George Romero--whose first big hit opened a seam of movie-dom that has been dug ever deeper to this day: Night of the Living Dead.

And for what it's worth, Pittsburgh still has more than 700 staircases officially registered as city streets.

Mar 12, 2010

With this picture and tomorrow's, Good Morning is turning the page on winter. The groundhog and the calendar and even the weather may say differently, but the groundhog and the calendar and even the weather do not control this here Good Morning thing, so . . . Goodbye, winter.

Last month, when the depth of the snow in Reading, Pennsylvania, could be measure in cubits or furlongs or some such, many people dug their cars out and then tried to reserve the parking spots they'd dug by setting chairs in them. This is probably an inherited cultural practice; if you are born into a family that believes in claiming parking spaces with chairs, then that's what you will grow up to do. It makes good sense to you, practical sense and also moral sense. You did the work of digging the spot clear; why should somebody else who didn't shovel a single flake get to take advantage of your hard work and park their car there?

But there are also people who believe that parking spaces on a public street are public and can't be claimed by any one person. No matter what the weather, it's first come, first served at the curbside. These people may be in the minority, but they also believe their approach is rational and morally superior--and often, as in this picture, they have the city government on their side. In Reading and many other places, the city came along and took all the chairs away. This practice has the effect of inspiring people, grudgingly, to shovel out additional parking spaces as needed.

In Portland, we don't have this kind of problem. The city bans parking the night after a big snowfall, and the plows quickly scrape almost all the streets clean, curb to curb. This solution would never work in places like Reading, where there may not be enough driveways to hold cars during a street parking ban and where there surely aren't enough plows to clear the streets promptly.

So next winter, a lot of people will feel strongly that they need to do that chair thing again. But meanwhile, I'm calling it spring. Goodbye, chairs.

Jul 18, 2010

By now, many of you have heard that we are headed to Philadelphia. The heavy lifting of the move has begun, so it'll be at least a week or so before I'll have a chance to share more Good Mornings with y'all. Please be sweet in the meantime, and don't pick on your siblings; we are, after all, moving to the City of Brotherly of Love.

I cannot say what's with the horses. They're tied up to a pay phone in front of PMV Variety Store in our neighborhood-to-be, just south of center city Philadelphia. If you Google-earth this spot, you'll see that the pay phone is still there and the storefront still looks the same, though the PMV Variety may now be out of business. The horses have vamoosed.

Jan 7, 2011

Arthur Havard was fourteen years old in 1911 when his picture was taken at work one day, outside the #6 shaft of the coal mine in South Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Arthur Havard was fourteen years old in 1911 when his picture was taken at work one day, outside the #6 shaft of the coal mine in South Pittston, Pennsylvania.

Havard's job was to drive the mules that hauled coal along tracks from the working face deep in the mine all the way up to daylight. Many boys worked in the mine for years as mule drivers until they finally grew big enough to wield a pick and work as regular miners.

It was another world back then. Yet it wasn't all that long ago; Havard's children were born in the 1920s, and some are still alive today.

Here is a description of how children worked in the mines of Pennsylvania, provided by the son of a mule driver like Havard:

My dad was a 'mule driver' in a Western Pennsylvania bituminous coal mine as a youth. His job was to guide the mule and coal cart on tracks out of the mine. On the way out, he would make sure that no clumps of coal would fall off the cart. If they did he would have to pick up the coal, climb to the top of the load and replace the fallen coal on top of the load. The coal company had a bell at the exit tunnel hanging down to ring as it was hit on the way out. If the bell did not ring, the team who cut, dug and loaded the coal would not be paid for a full load. He could never let that bell not to ring. That team of miners were his relatives and neighbors in the same Coal Patch.

Jun 26, 2011

Last week, baby Calla's visit back in Pennsylvania with the family included a little time on all fours out in the yard. A good time all around, according to Grandma. But on Friday, it was back to the airport for a long, long ride on a plane–back home to Zambia, in Africa.

Last week, baby Calla's visit back in Pennsylvania with the family included a little time on all fours out in the yard. A good time all around, according to Grandma. But on Friday, it was back to the airport for a long, long ride on a plane–back home to Zambia, in Africa.

Jul 8, 2011

Every few minutes at Victor Cafe in South Philly, one or another of the servers rings the little bell seen here on a tabletop and bursts into song.

Every few minutes at Victor Cafe in South Philly, one or another of the servers rings the little bell seen here on a tabletop and bursts into song.

They all have operatic training, so usually they sing opera, which is what the crowd came for–and they do draw a crowd. But as the evening progresses, the repertoire loosens up a little; they belt out showtunes as well as arias, and they even take requests. Here, at the end of the night, a tenor working as a waiter closes down the place with that old pop standard, Ave Maria.

Aug 25, 2011

Sadly, this is a "before" picture: the big American Elm tree in the courtyard of Shiloh Baptist Church in our neighborhood has been diagnosed with Dutch Elm Disease and is about to be cut down.

Sadly, this is a "before" picture: the big American Elm tree in the courtyard of Shiloh Baptist Church in our neighborhood has been diagnosed with Dutch Elm Disease and is about to be cut down.

I'm told this tree made a cameo appearance in The Sixth Sense, a Bruce Willis movie shot in the neighborhood, but I can't confirm or deny. There's a pivotal scene near the end of the movie in which the boy and his mother sit talking in the car, which is stopped near the scene of an accident; there's a tree outside the car window on the boy's side, but all the camera shows of this tree is its lower trunk, which is not sufficient for a positive ID.

Anyway, the church building and probably also the tree date back to the 1860s, when the Church of the Holy Apostles was built to serve a neighborhood rapidly filling with immigrants from Ireland. Numerous annexes and additions were required, as the parish exceeded 10,000 by 1910. But by 1940, descendants of the Irish immigrants were leaving the neighborhood, and descendants of African slaves from the American South were pouring in. The church complex was sold to a Baptist congregation and renamed Shiloh.

Today, Shiloh's congregants have mostly left the neighborhood, replaced this time by newcomers who mostly grew up in middle-class suburbs; one long-time resident described the new neighbors to a newspaper reporter as "white people with big dogs." Churchgoers who've moved away return to Shiloh on Sunday mornings, causing traffic jams and parking conflicts. There is no church parking lot; for the church's first hundred-plus years, people got there by walking.

The congregation is shrinking fast and is already far too small to maintain the huge church complex. The elm will come down in the next few weeks; the building, designed by the iconic Philadelphia architect Frank Furness, may not be far behind.

Oct 27, 2011

Above, you see what's left these days of Centralia, Pennsylvania, once a busy little coal-mining community, now literally a smoking ruin. Seams of coal in the ground underneath Centralia have been burning for almost fifty years now, despite millions of dollars spent on fire-fighting efforts. The townspeople have all been relocated and their homes and businesses demolished, but still the fire burns, heating the ground from below, venting smoke through cracks in the earth. Researchers estimate it will burn itself out in another couple of hundred years.

Above, you see what's left these days of Centralia, Pennsylvania, once a busy little coal-mining community, now literally a smoking ruin. Seams of coal in the ground underneath Centralia have been burning for almost fifty years now, despite millions of dollars spent on fire-fighting efforts. The townspeople have all been relocated and their homes and businesses demolished, but still the fire burns, heating the ground from below, venting smoke through cracks in the earth. Researchers estimate it will burn itself out in another couple of hundred years.

Centralia had its fifteen minutes of fame about thirty years ago, when residents finally gave up on fighting the fire and voted to abandon their homes. What was not widely discussed at the time, however, was that although coal fires can occur as natural phenomena, this one was no act of God; it was intentionally set by Centralia's own fire department as part of a routine practice of burning off garbage in the town dump. In 1962, however, the town acquired a new landfill: a long-abandoned anthracite strip mine. When the fire department lit its regular garbage fire in the new dump, an exposed coal seam caught fire.

For twenty years, townspeople fought the fire and tried to live with it. But in 1981, the owner of an Amoco gas station was checking the level of fuel in his underground storage tank when he noticed that the dipstick seemed hot. A thermometer lowered into the tank revealed that the temperature of the gasoline was 180 degrees.

There were numerous complaints of people experiencing symptoms associated with carbon-monoxide poisoning, and the city bought carbon-monoxide detectors for every home. But Centralians still didn't give up on their town until the day that a sinkhole suddenly cracked open beneath the feet of a twelve-year-old boy. He slipped part of the way down into the hole, which was about four feet wide and more than a hundred feet deep, hot and smoking and belching poisonous fumes. The boy's cousin grabbed his arms and was able to rescue him before he fell all the way in, and shortly thereafter, the U.S. Congress came up with $42 million to relocate all 1,000 men, women, and children of Centralia.

Underground coal fires are actually fairly common, especially in China and Indonesia, where it is believed that as much as 10 per cent of all the known coal reserves may have caught fire while still in the mines. About 200 coal fires have been identified in the United States, mostly in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. In the U.S., most coal fires are far from populated areas and are started by sparks from wildfires or lightning strikes in coalbeds. There is geological evidence of coal fires burning many millions of years ago, and it has been calculated that over time, coal-fire emissions of carbon dioxide and other toxic gases may have significantly impacted global warming.

Coal fires are notoriously difficult and expensive to fight, and efforts to put them out often wind up making them worse, feeding the flames with fresh air. In 1982, experts consulted by Centralia proposed an elaborate trenching operation that would cost $440 million and might or might not work. Voters rejected the scheme, and presumably they have now gotten on with their lives, wherever they have gone. A reunion is set for 2015; on the agenda is the opening of a time capsule sealed in 1965, during construction of what was then the new town bank.

In the photos below:

(1) A block in downtown Centralia, from a 1986 photo. All the buildings were razed except for the Speed Shop bike store near the righthand edge of the picture, which caught fire.

(2) Smoke from cracks in the ground, as seen last week. In many parts of town, we could feel the heat through our shoes.

(3) New wind turbines on the ridge north of Centralia. Energy produced by these few windmills must be trivial compared to the energy once dug out of the earth here, which in turn may be trivial compared to the energy wasted by the mine fire. But a new page is turning in the history of this coal country.

Oct 30, 2011

Friday was the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center's second annual Philly Photo Day. Anyone can submit a digital file for a photo taken anywhere in the city during the twenty-four-hour period of October 28; the Photo Arts Center prints the pictures and offers them for sale at a fund-raising gala. My submission was this snapshot from the checkout line at an ABC store, where Philadelphians were getting ready for the weekend.

Friday was the Philadelphia Photo Arts Center's second annual Philly Photo Day. Anyone can submit a digital file for a photo taken anywhere in the city during the twenty-four-hour period of October 28; the Photo Arts Center prints the pictures and offers them for sale at a fund-raising gala. My submission was this snapshot from the checkout line at an ABC store, where Philadelphians were getting ready for the weekend.

Oct 31, 2011

Appropriately enough, what you can see from the top of Castle Rock, just outside World's End State Park in the Endless Mountains of Sullivan County, Pennsylvania, are endless trees and endless mountains. Way down below is a tributary of Loyalsock Creek, which spills heedlessly over waterfall after waterfall en route to the west fork of the Susquehanna.

Appropriately enough, what you can see from the top of Castle Rock, just outside World's End State Park in the Endless Mountains of Sullivan County, Pennsylvania, are endless trees and endless mountains. Way down below is a tributary of Loyalsock Creek, which spills heedlessly over waterfall after waterfall en route to the west fork of the Susquehanna.

It is definitely the time of year to wear bright orange in these woods.

Nov 1, 2011

On a crisp October Saturday, deep in the Loyalsock Canyon of World's End State Park, you have to wait on line for your turn to take pictures of the waterfalls.

On a crisp October Saturday, deep in the Loyalsock Canyon of World's End State Park, you have to wait on line for your turn to take pictures of the waterfalls.

Ordinarily, creeks and waterfalls have shriveled to a trivial trickle by this time of year. But after a wet, wet summer and then the floods of Hurricane Irene, waterways throughout Pennsylvania are putting on a show.

Dec 1, 2011

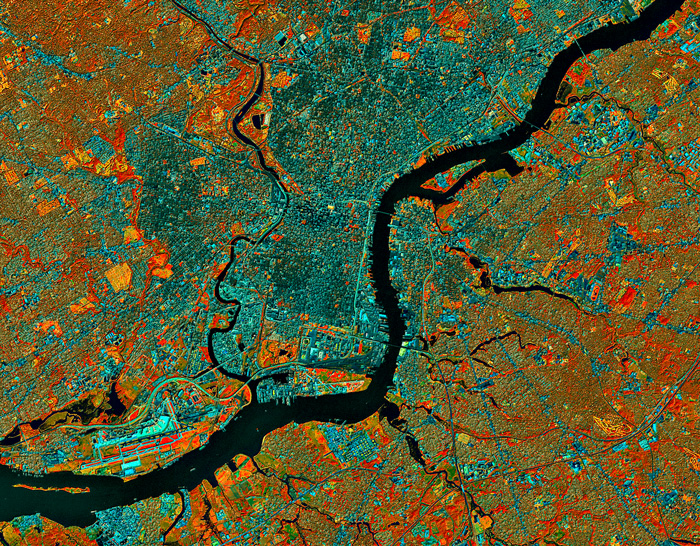

At about 9:30 in the morning on September 23, 1999, the Landsat 7 satellite swooped southward over eastern North America and captured this image of Philadelphia and environs.

At about 9:30 in the morning on September 23, 1999, the Landsat 7 satellite swooped southward over eastern North America and captured this image of Philadelphia and environs.

Three of the Landsat sensors detected energy in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum, completely invisible to the human eye. Data from these sensors is displayed here, with each of the three infrared bands assigned to one of the normal red-green-blue color bands so we at least have something to look at, even though the colors have nothing to do with normal vision.

Clicking on the picture brings up a bigger version, which shows much more detail.

We can tell right away that the rivers are black; infrared energy is completely absorbed by water, reflecting back nothing for the sensors to detect. And if we look along the river at lower left, we can make out the airport, with runways that are bright cyan in color. This white-to-bluish hue is also the color of roads, railroads, parking lots, and other paved surfaces.

Infrared data is especially useful for studying vegetation, which shows up in this color scheme as red, orange, or yellow. The brightest red patches represent vigorous herbaceous growth, such as healthy cropland in the midst of the growing season. There's little or no farmland in and around Philly, however, so the red patches we see here, such as in between the airport runways, are probably healthy weeds.

Patches of red coloration with a touch of an orange tint and some texture are forested areas, such as in parks or between the fairways of golf courses. Extremely vigorous grass, such as on the golf course fairways themselves, looks bright yellow in this view.

The brownish-to-grayish-to-bluish areas show mixed land cover: Landsat's sensors are averaging out the infrared signals from house roofs, pavement, lawns, shrubs, and trees in varying concentrations. Brownish areas are suburban, with lots of trees and grass; dark green to gray-blue areas are more urban, with a higher ratio of rooftops and pavement to vegetation.

Philadelphia has changed since this image was captured twelve years ago. Another stadium has been built near where the Schuylkill River empties out into the Delaware. In my neighborhood just south of Center City, the forested patch of land near the Schuylkill, which in 1999 was an abandoned and overgrown Old Sailors' Home is now a heavily developed condo complex. Even though the population of Philadelphia has shrunk dramatically over the past half-century and has just barely started growing again, land use patterns as viewed from outer space show ongoing urbanization.

Nov 28, 2012

It does seem like we don't make anything in America any more, but that's not completely true. Right here under this roof in Easton, Pennsylvania, Americans make Crayola crayons and . . . Silly Putty. Not only that, but up the road a few miles they've got a factory outlet store and a Crayola Discovery Center, which is basically a crayon-themed theme park.

It does seem like we don't make anything in America any more, but that's not completely true. Right here under this roof in Easton, Pennsylvania, Americans make Crayola crayons and . . . Silly Putty. Not only that, but up the road a few miles they've got a factory outlet store and a Crayola Discovery Center, which is basically a crayon-themed theme park.

Still and all, this factory doesn't look quite right. You can't make a lot of crayons without heating up a lot of wax–shouldn't they have some serious smokestacks here?

Jan 31, 2013

This 1880s-era bridge connecting the Allegheny County courthouse with the jail in downtown Pittsburgh is a fair replica of the seventeenth-century Bridge of Sighs in Venice, which connected the prison with the interrogation chambers in the doge's palace.

This 1880s-era bridge connecting the Allegheny County courthouse with the jail in downtown Pittsburgh is a fair replica of the seventeenth-century Bridge of Sighs in Venice, which connected the prison with the interrogation chambers in the doge's palace.

In Pittsburgh as in Venice, prisoners being escorted across the bridge were said to catch a final glimpse of life on the outside before disappearing into the labyrinths of judicial inquistion and disposition. In both cities, too, the bridges and buildings survive to this day; the courthouse building at right in this picture is still an active courthouse, though the jail building at left now houses the county Family Services agency.

Modern-day photos, however, reveal an oddity: the bridge now appears to loom much higher above the street than it did back in 1903, when the picture above was taken. An urban-improvement project known as the Hump Cut, completed in 1913, flattened out major downtown streets in Pittsburgh, lowering Fifth Avenue here by several feet.

Nov 6, 2013

Lily wraps one of her custom-created alliterative labels around a naked crayon at Crayola's play park in Easton, PA. Among her names for crayon colors: Lily Lemon, Lily Lollipop, Marvelous Mom, and Naughty Norman.

Lily wraps one of her custom-created alliterative labels around a naked crayon at Crayola's play park in Easton, PA. Among her names for crayon colors: Lily Lemon, Lily Lollipop, Marvelous Mom, and Naughty Norman.

In the huge Crayola factory just outside of Easton, where all 64 colors are melted and molded and labeled and boxed and shipped out to the world, the wrapping of labels is of course done by machine. But until the wrapping machines came on line in the late 1930s, that part of the process was farmed out to families in the Easton area, who would work at their kitchen tables wrapping labels around each crayon individually for a piecework wage. Each family worked on a single color, and the delivery routes were organized by color: e.g., turn left at the Green house and go up the hill to the Blue place.

Modern crayons first showed up at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, where Crayola exhibited them as "dustless chalk," a healthful innovation for the classroom. The company that made them, Binney & Smith, was getting a little out of its comfort zone, since its main facility in Easton was a slate quarry, which provided slates for schoolrooms utilizing the non-dustless kind of chalk.

Today, Crayola's theme park and factory undergird the economy of Easton, which was once home as well to the headquarters of another corporation manufacturing the stuff American childhood used to be made of: Dixie Cups.

Nov 25, 2013

Both of these Brittany Spaniels–bird dogs, for certain sure–believe they're onto something, here in a Pennsylvania marsh where just a few short months ago, sunflowers were smiling.

Both of these Brittany Spaniels–bird dogs, for certain sure–believe they're onto something, here in a Pennsylvania marsh where just a few short months ago, sunflowers were smiling.

Jun 24, 2014

The bird looks happy–happy that it's not November?–but it's fattening up nicely.

The bird looks happy–happy that it's not November?–but it's fattening up nicely.

Aug 8, 2014

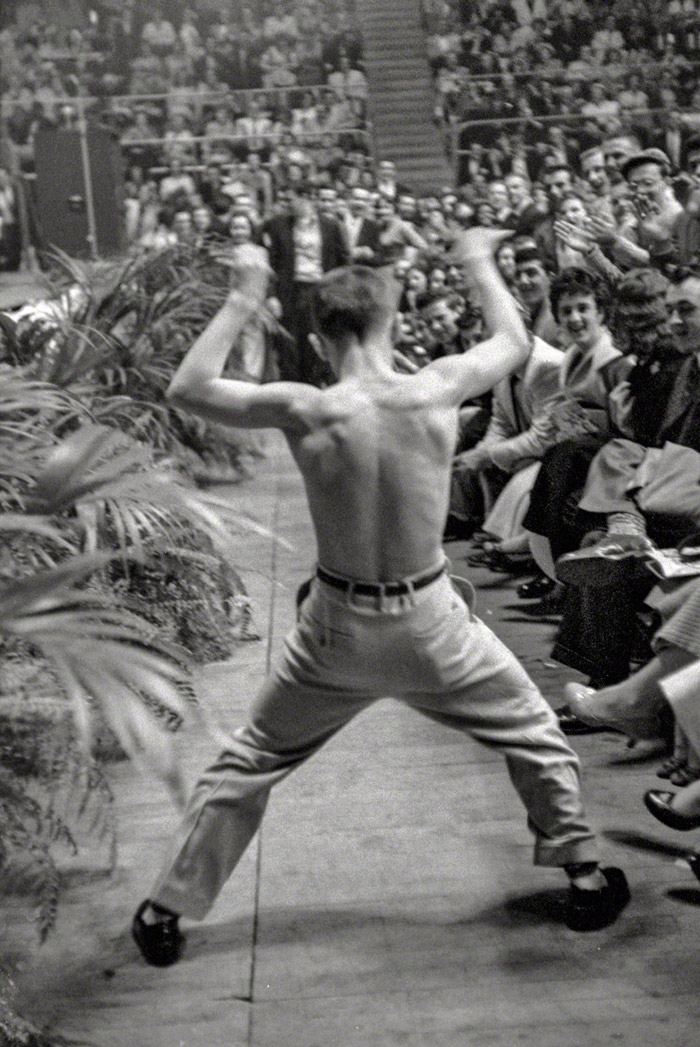

Bill Haley and the Comets were on stage, and this young man was in the audience during an April 1956 concert at the Sports Arena in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The opening act was LaVern Baker.

Bill Haley and the Comets were on stage, and this young man was in the audience during an April 1956 concert at the Sports Arena in Hershey, Pennsylvania. The opening act was LaVern Baker.