Hole in the Clouds

Sep 6, 2009

There will come a day when nobody cares about Alabama football any more. True, we're not there yet. We'll probably have single-payer health care in the United States long before the Crimson Tide roll over and play dead.

As I write this, Alabama is losing its first game of the season 16-17, to Virginia Tech. They're playing in Atlanta tonight, in the Georgia Dome, but some sunny Saturday very soon, Bryant-Denny stadium in Tuscaloosa will once again look exactly like this.

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa

sports

football

Alabama

(Image credit: unknown)

Sep 4, 2009

Joe Stein is admiring dinner. It should be tasty, thanks to Joe's buddy Joe Fair, who went catfishing the other night in the Black Warrior River near Moundville, Alabama.. According to one of the Joes, it took an hour to reel in the big guy.

Alabama

animal

food

fish

Joe Stein

Joe Fair

(Image credit: Joe Fair)

Aug 30, 2009

The supply closet at the back of Tommy Flowers's math classroom at University Place Middle School in Tuscaloosa has won official recognition as the world's smallest museum.

Mr. Flowers, who has been teaching for 25 years, has assembled a collection of Edgar Allan Poe artifacts, including plastic hearts, dozens of photos, a skull, and of course, a skeleton. He says he became fascinated with Poe when he was himself in junior high school, and he tries to weave Poe's stories and poems into his students' daily lessons.

The fact that he teaches math, not literature, has not been an obstacle: he wants his students to take inspiration from Poe as they cultivate their imaginations to get the most out of life. Also, he wants them to calculate the square footage of his museum--the answer to that is 22, which is the magic number that got Edgar's Closet desgnated as smallest museum in the world.

"I d like a few visitors," said Mr. Flowers. "But more than anything, I'd like to see a few teachers have museums in their closets."

All five Stein boys went to University Place when it was an elementary school. It has recently added middle school grades as part of the Tuscaloosa City Board of Education's scheme to re-segregate the public schools. So far, there have been numerous complaints and petitions, but no lawsuits, so it's working.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

University Place School

museum

Edgar's closet

Tommy Flowers

Edgar Allan Poe

(Image credit: unknown)

Aug 5, 2009

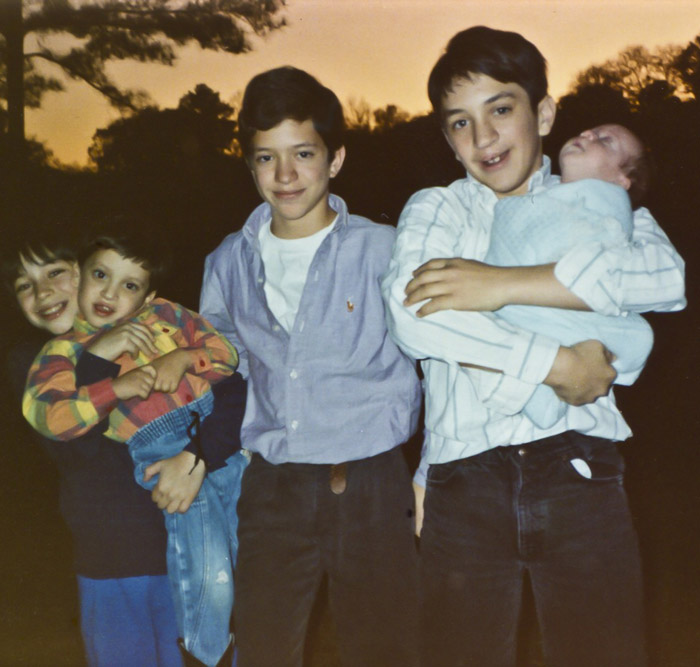

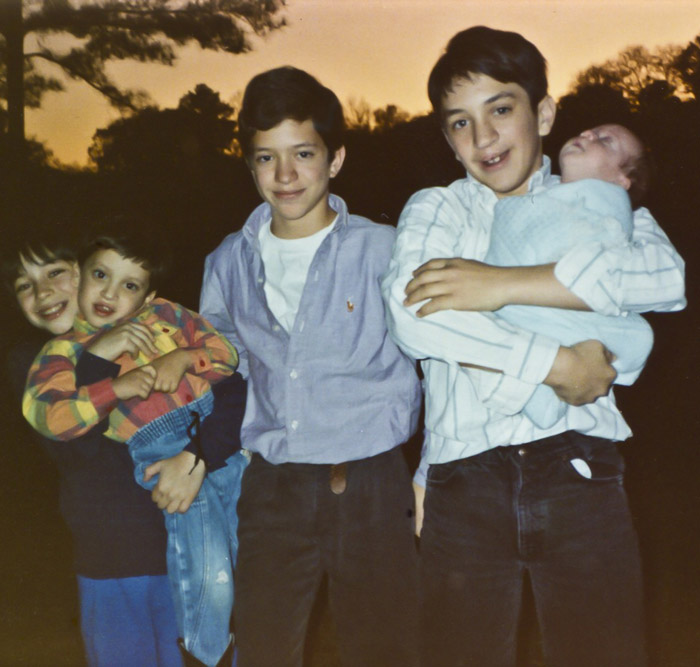

This photo is ten years old now. Since then our five boys have rarely shown up in the same time zone, much less the same picture frame--this is an important document in family history.

The original negative is gone; there may be some high-resolution prints around somewhere, but I'm not sure where. What I've got on my computer is a scratched, speckled, and stained scan comprising just a handful of pixels.

This gussied-up version is only arguably better than the straight scan. Whatever: from left, in order of age, that's John, Ted, Joe, Allen, and Hank.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

John Stein

Joe Stein

Ted Stein

Allen Stein

Hank Stein

Forest Lake

(Image credit: Carol Stack)

Oct 21, 2009

For many years now, as the University of Alabama has expanded its football stadium, it's been interested in a small piece of land across the street from the stadium that was home to Temple Emanu-El of Tuscaloosa. The university and the congregation finally agreed to a land swap, and a new synagogue building is now under construction across campus. This past month, the frame went up.

It's not clear what the university will do with its new land--"Some more game-day something or other," according to Anna Singer, who chairs the Temple Emanu-El building committee.

University of Alabama

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

cranes

(Image credit: Anna Singer)

Oct 30, 2009

Please forgive me for writing here about Alabama football--just this once, I promise, at least till next year.

Some people don't like football. And even among those who do like football, some don't like Alabama football. All I can say is: better luck in your next life.

Nobody doesn't like Terrence Cody--Mount Cody--the unheralded defensive lineman from Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College who showed up for practice in Tuscaloosa weighing 400 pounds. Off the field, they say, he's a gentle, teddy bear sort of guy, who likes cartoons on TV and sleeps on Spiderman sheets. On the field, he's not gentle; Alabama's defense is ranked number one in the nation, and on that defense Cody has participated in more than his share of tackles and sacks. Last Saturday, he saved a close game for the Tide by blocking two field goal attempts, including one in the final seconds of the game.

But Mount Cody's value to the team doesn't really show up in the formal statistics. Basically, he is so big and strong that the opposing team will need two guys to contain him. This double-teaming gives his teammates a numerical advantage; because of Cody, somebody else is wide open to make more tackles and sacks.

Last Saturday, Tennessee put two guys on Cody, the Sullins brothers, identical twins who are big, strong, experienced offensive linemen. They each weigh something like 275 pounds. Cody has trimmed down a bit; even at 400 pounds he had moves, but now at 365 he can almost run. Still, he outweighed either of the Sullins boys by a good 90 pounds. Several times during the game, double-teaming didn't work to stop him; he would swat the first guy out of the way before the second guy showed up to help--and when Cody gets moving, it might take three or four guys to stop him.

Bama has a number ofl exciting players, including defensive linebacker Rolando McClain, who seems to be a football genius, always guessing right about what the other guys are going to do with the ball. On offense, there's the ridiculously fast receiver Julio Jones and the running back Mark Ingram, a sort of zombie runner who won't stay dead.

But last week was all about Mount Cody. Here he is, number 62, blocking a kick., Notice the Tennessee player lying down in front of him, number 69--that's one of the Sullins brothers, just trying to do his job.

Tuscaloosa

sports

football

Alabama

Crimson Tide

Terrence Cody

Mount Cody

(Image credit: Tuscaloosa News)

Nov 11, 2009

For a million years--34, to be exact--the sixth-grade gym teacher at Westlawn Middle School in Tuscaloosa was Yvonne Wells. So far as I could tell, Ms. Wells was a perfectly normal physical education teacher, who probably went home hoarse every night after a hard day's work.

When she got home, she took up her needle and thread and scissors and spread out her fabrics on the living room floor and went to work quilting. Sometimes she stayed up half the night. She'd had no training in quilt-making, and when she tried to reproduce the old patterns, she felt frustrated and dissatisfied with the results. Gradually, she abandoned traditional patchwork for her own intensely personal, and often political, storytelling style of quilt.

Wells sells her quilts at festivals and in galleries; almost all her work, she says, winds up hanging on the wall instead of laying across a bed. Her style has attracted attention far beyond Tuscaloosa, and in recent years her work has been featured in traveling exhibits at museums all over the country. Half a dozen of her quilts, including this one, are now part of the permanent collection of the International Quilt Study Center and Museum in Nebraska.

What we see here is the Statue of Liberty holding dollar bills in one hand and a black person, perhaps a child, in the other, while she stomps on an Indian with both feet. The title pretty much says it: Being In Total Control of Herself, B.I.T.C.H.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

art

Yvonne Wells

Statue of Liberty

quilt

Westlawn Middle School

teacher

Jan 5, 2010

All five Stein boys touched down in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, a few days ago and claimed the beachhead for the Crimson Tide. That's not very hard to do in Tuscaloosa.

The occasion was the premier social event of the year, on New Year's Day, the wedding of Neely Sims and Damon Ray.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

night

Crimson Tide

John

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

Jan 18, 2010

Neely and Damon were married on New Year's Day, 2010, in Tuscaloosa. The cake decorations are just what they look like: American childhood delicacies.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

wedding

twinkies

hostess cupcakes

little debbie cakes

Jan 20, 2010

All five Stein brothers in an elevator, on the first day of 2010.

From left to right: #3, #1, #4, #5, #2 (1981, 1978, 1988, 1992, 1979).

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

John Stein

Ted Stein

Allen Stein

Hank Stein

Joseph Stein

elevator

Feb 5, 2010

Why do people keep dumping noxious, toxic, no-good very bad stuff in west Alabama? Which do you want first, the geologic reason or the political reason?

The geologic reason is a thick, 100-million-year-old layer of chalk that sits not far below the surface in Sumter County, Alabama, and thereabouts. You can make compelling arguments that this chalk is pretty much impermeable, sealing off any pollutants that might be deposited in a hazardous-waste landfill, such as the Arrowhead facility pictured here. (The only problem with those arguments is that unmapped faults deep in the chalk seem eventually to compromise these landfills; over time, they all spring leaks.)

The political reason is that west Alabama is desperately poor and majority African American. Local governments in less desperate parts of the country would not allow projects like Arrowhead, which clearly put citizens' health at risk and drive away more reputable industrial development. But where there are no jobs and no tax base, an opportunity to store other people's dangerous filth can seem better than no opportunity at all.

And so it came to pass that companies operating the Arrowhead landfill won a supposedly lucrative contract to "dispose of" a billion gallons of waterlogged coal ash that had spilled near Kingston, Tennessee, last year when a retention pond failed outside a power plant.

Arrowhead's neighbors soon complained of horrible odors and other concerns. They threatened to sue. Arrowhead immediately declared bankruptcy, claiming that people from New Jersey had run off with all the money from the cleanup contract. They are now un-sueable, but at last word, trucks were still pulling up to the landfill day and night with loads of coal ash to dump.

Alabama

landfill

hazardous waste

coal ash

Sumter County

(Image credit: John Wathen)

Feb 22, 2010

Winter is still with us, or at least with many of us, and there will soon be at least one more quick glance at icy cold stuff through that hole in the clouds. But let's hear it for daffodils in February.

This photo was taken yesterday in Tuscaloosa. The thing about spring in Alabama is that it starts right about now and goes on and on and on, growing flowerier and flowerier, month after month, till finally, some time in May, the air disappears and it's just too hot.

The daffodils are nothing but a tease, along with the quince blossoms and the Japanese magnolias. Then the wisteria and the redbuds. Until finally, around the beginning of April, it's seriously spring, with dogwood above and azalea all over. (The big Southern magnolias don't bloom till June, when it's hot, so I count them as summer flowers.)

They had hard freezes this winter in Alabama and even a little snow. But by yesterday, according to our Tuscaloosa correspondent, it was 70 and sunny.

Alabama

flowers

spring

(Image credit: Anna Singer)

Jun 26, 2010

We have all seen pictures of the oil gusher in the Gulf of Mexico; this is the one that put a catch in my breath today.

Nicole Kesterson of Gulf Shores, Alabama, is snapping a picture at the public beach near Gulf Shores State Park, while blackened surf splashes down onto the sand. Used to be, Gulf Shores and nearby beaches were characterized by what people called "sugar sand"--fine, white, perfect, clean quartz crystalline sand. I've seen tarballs there before--Gulf oil platforms are visible from many parts of the beach--but black waves of crude are something else again.

Picture these gentle little waves roughed up and built into mountains by a hurricane--Atlantic and Gulf waters are warmer this summer than ever before in human history, and hurricanes are the earth's major mechanism for dealing with hot spots of subtropical water. The oil will come crashing inland, obviously, surging for miles to flood uncleanable marshes and swamps. And evidence is accumulating that thanks to BP's massive use of dispersants, oil will also likely be sucked up into the sky; oil vapor will gather in the clouds along with water vapor to rain poison down on us all.

For what it's worth, the good news is that mosquitoes don't do well in oily environments.

I have spent enough time among geologists to accept that all substantial reservoirs of oil on the planet will eventually be tapped for human use. But what I hear about energy policy in America these days seems completely backwards to me: why aren't we letting the Saudis and the Russians let their wells run dry before we tap into our own precious reserves? Countries with no other source of income or with desperate economic problems have no choice but to sell off all their oil as quickly as possible. We're rich enough to wait for a while, and as the rest of the world's oil disappears, ours becomes more and more valuable. Perhaps eventually it will be worth so much that oil companies will be cautious not to risk spilling a drop.

Or whatever.

Alabama

beach

Nicole Kesterson

BP

oil

Gulf Shores

(Image credit: John David Mercer of the Mobile Press-Register)

Nov 19, 2010

About twenty years ago, we went paddling round a bend in the Little Cahaba River near Montevallo, Alabama, and came upon this rope swing. It looked like fun, but even twenty years ago I was a boring old lady without the gumption to give it a try.

Alabama

Little Cahaba River

boys

rope swing

swimming

Dec 19, 2010

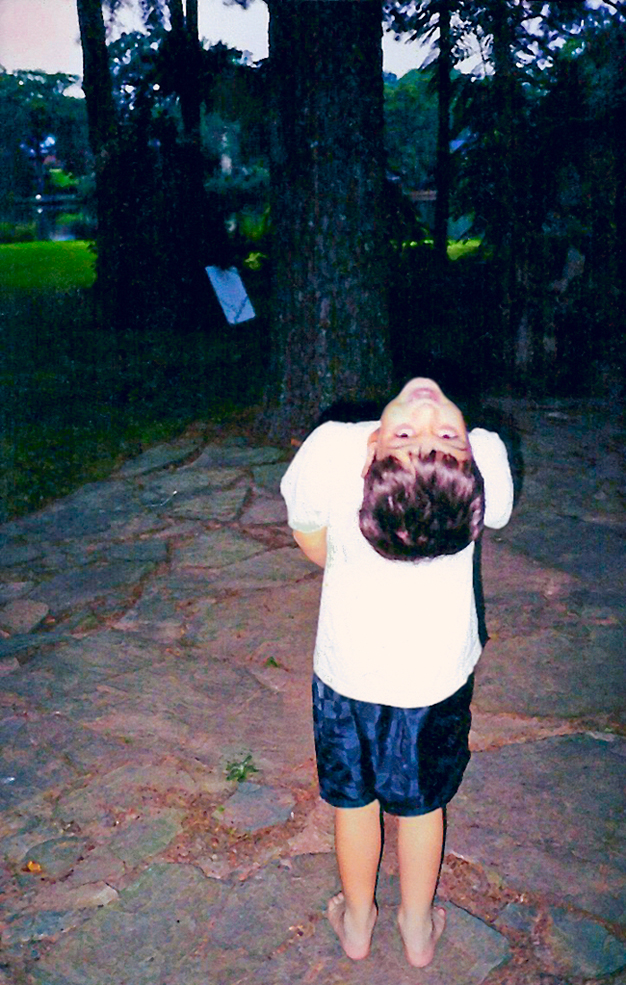

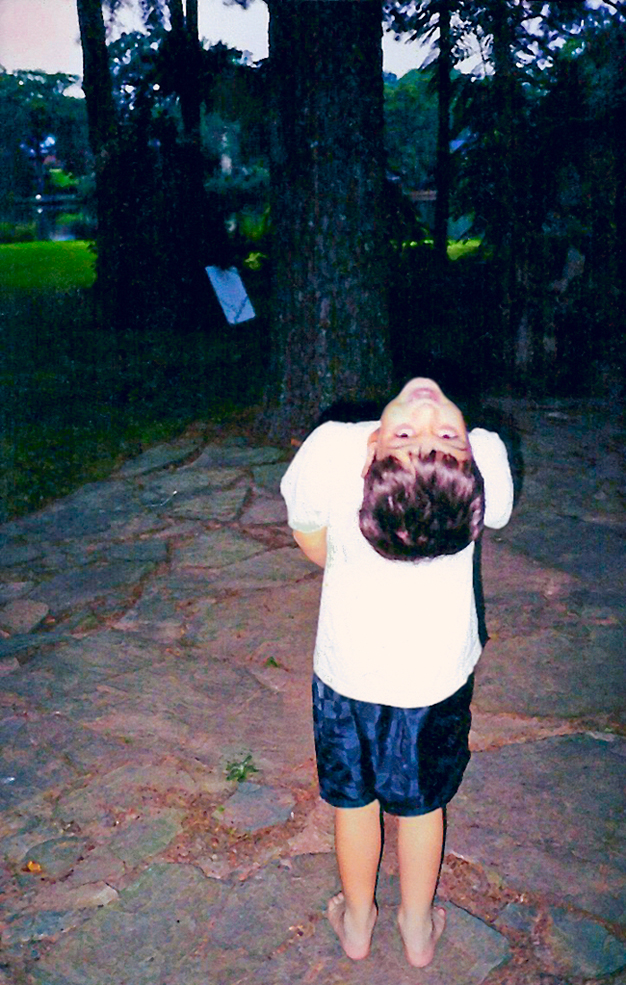

Young Hanky got himself into this pose all by himself, with no help from Photoshop. The flexible back and seriously sturdy neck would serve him well athletically when he became a high school wrestler, but back in 1998, when this photo was probably taken, he had other interests, notably Beanie Babies. Rumor has it that as of this weekend, he's finished his first semester of college and shipped his snowboard back to Maine for some serious semester break.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

kids

Hank Stein

yard

contortion

May 1, 2011

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

This is what one of the storms did to the house in Tuscaloosa where we raised our children. At least I think that's what we're looking at here; if it's not our old house, it's the house next door; there's not enough left to know for certain. The picture is disorienting in part because the house in the foreground near the waterfront, amongst the trees, must have been blown in by the storm from somewhere else; none of the houses on that side of Forest Lake was built so close to the water.

It's been forty years since an American city was shredded like this by an EF5 tornado, with winds exceeding 200 miles per hour; the last such storm was in 1970, when 26 people died in Lubbock, Texas. Wednesday's storm crossed through the middle of Tuscaloosa from southwest to northeast, devastating a path up to a mile and a half wide--about as wide as tornado paths ever get, according to the meteorological commentary I have been reading obsessively.

In some spots, winds were so strong that they ripped up the pavement and tore culverts out of the ground.

Our old neighborhood, Forest Lake, is pretty much in the geographic center of town. Most of it is gone now. The neighborhood just to the northeast, Cedar Crest, was hit even worse, if you can imagine that, and beyond Cedar Crest the neighborhood of Alberta City was completely obliterated, many houses reduced to clean slabs, with the debris sucked so high into the sky it returned to earth fifty or even a hundred miles away.

The house we lived in before this one was also destroyed, as was the elementary school all five of our boys attended.

We've been able to get in touch with almost all our old friends and neighbors, and they seem to be among the relatively lucky Tuscaloosans--homeless in some cases, but safe and sound. As of Saturday, the local death toll was 39 but expected to climb as rescue crews complete their search through the ruins.

More than 5,000 houses are damaged, and over 1,000 people have been treated for injuries at the hospital.

From now on, life in Tuscaloosa will be divided into a before and an after.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Forest Lake

tornado

home

May 12, 2011

The April 27 tornado that stayed on the ground for more than eighty miles through Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, has now been classified F4, not F5, as I mistakenly indicated in a posting here on May 1. There were three definite F5 tornadoes that same day, including one in north Alabama that completely obliterated the town of Hackleburg.

The April 27 tornado that stayed on the ground for more than eighty miles through Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, has now been classified F4, not F5, as I mistakenly indicated in a posting here on May 1. There were three definite F5 tornadoes that same day, including one in north Alabama that completely obliterated the town of Hackleburg.

But F4 is plenty bad enough. Forty-one people died in Tuscaloosa.

This is what's left of our old house. It was a two-story house, but the second story was set back a bit, and it's completely gone. At the extreme right of the picture is the doorframe for the front door, which is gone. At left is a spray-painted "Katrina cross" indicating that the rubble was searched on April 28 by search team "M," and no people or pets were found.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

house

ruins

tornado

(Image credit: Ben Shankman)

Jun 9, 2011

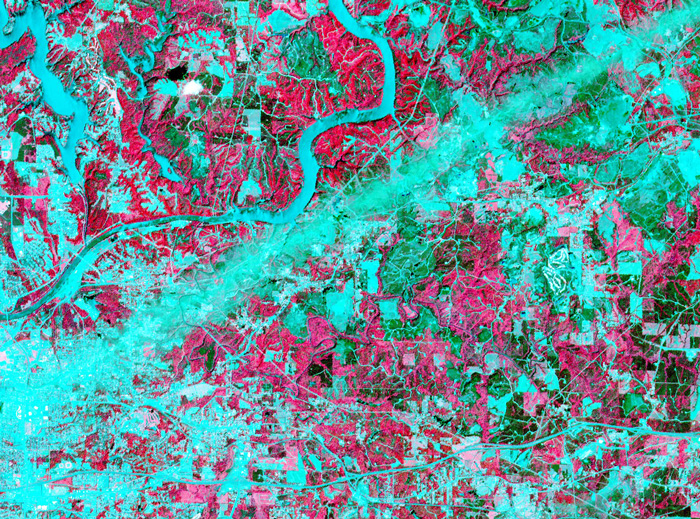

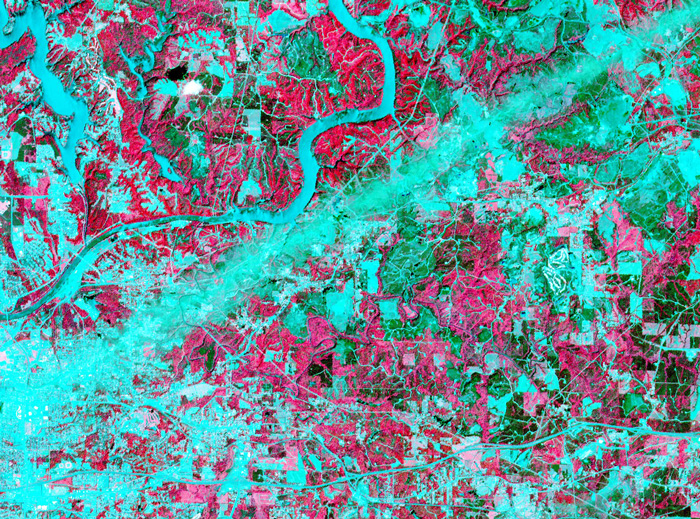

On April 28, 2011, the visible-light and infrared sensors of NASA's ASTER satellite captured this image of Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, which had been raked by an especially large and powerful tornado just the day before.

On April 28, 2011, the visible-light and infrared sensors of NASA's ASTER satellite captured this image of Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, which had been raked by an especially large and powerful tornado just the day before.

Infrared sensors are useful for distinguishing between vegetated and non-vegetated land cover. The pink areas in the photo represent vegetation–forests, pastures, cropland, golf courses. Areas that show up as aqua are non-vegetated or very lightly vegetated–cities, highways, rivers, strip mines, recent clearcuts.

The tornado track is obvious here: a straight aqua-colored streak running from the southwest to the northeast. Vegetation in this streak that was not directly destroyed by the storm was so littered with pieces of buildings and household objects that satellite sensors could barely detect it.

Just north of the storm track is the twisting course of the Black Warrior River, which shows up in aqua. The city of Tuscaloosa is mostly south of the river, at the left edge of the picture. In the upper left corner of the picture is Lake Tuscaloosa, a dammed-up tributary to the Black Warrior that provides the city's drinking water.

NASA's spokespeople assert that images such as this one can be useful in the aftermath of storms. They may help identify storm-damaged places outside of populated areas, where tornadoes might escape public awareness. And by proving the time and location of tornado paths, they could help homeowners support their insurance claims for storm damages.

If you click on the picture to see the larger version, you can follow numerous roads out into the countryside and observe that many of them seem to end with a little dot of aqua, indicating a non-vegetated spot. These are well pads for methane rigs. About fifteen years ago, the Black Warrior basin was the scene of one of the nation's first methane gas drilling booms. Coalfields underlie much of west Alabama, including almost all of Tuscaloosa County, but until recently the methane gas associated with coal deposits was considered a danger rather than an economically valuable fuel. "Fracking" technology, in which high-pressure liquids are injected deep into the earth to crack open the rocks hosting methane, was developed and refined in Alabama; drilling for methane is now under way all over the world. Unlike oil or traditional natural gas, methane is best extracted by small wells located within a few hundred feet of numerous other small wells; thus, the countryside is speckled with hundreds or thousands of separate well pads.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

birdseye view

infrared

satellite imagery

tornado

methane

fracking

(Image credit: NASA ASTER satellite)

(h/t: Chuck Horowitz

Sep 12, 2011

Once upon a time, about ten days ago, the Carnes family of Cottondale, Alabama, noticed that a llama had taken up residence on a hillside way at the back of their property. It was skittish around people and ran off when they approached, but the next day it was there again.

Meanwhile, at the very same time and less than half a mile away, the Smith family, also of Cottondale, noticed that one of their llamas was missing, and that the chain-link fence around their pasture was damaged. The Smiths had bought three llamas, including a baby, its mother, and another female, just three days earlier, partly because they'd been told that the presence of llamas can discourage predators such as wildcats from attacking other livestock. It was the mother llama that had come up missing.

There had been reports of a cougar in the vicinity, and the Smiths, who raised horses, geese, and ducks, had recently lost a dog to wounds that the vet told them were probaby inflicted by a cougar.

The Smiths feared the llama may have been another cougar victim. A mother llama would not normally abandon her young, they believed. And llamas almost always prefer to hang with their herd; they rarely venture far on their own.

The Smiths asked their neighbors, but nobody had seen anything. The Smiths did not know the Carneses, and apparently the Smith neighbors were not in close contact with people who were in contact with the Carneses, who were also making inquiries.

The Carneses checked with the sheriff's office, but there were no missing-llama reports. They finally called up the Tuscaloosa News, which sent out a photographer and ran a feature story about a mysterious wayward llama. If nobody claimed it, the Carneses told the newspaper reporter, they'd eventually try to catch it and turn it over to the Humane Society, which ran a sanctuary ranch for wayward llamas in Oliver Springs, Tennessee. But so far, the animal had run away whenever they came near.

The Smiths did not subscribe to the Tuscaloosa News, but they had friends who did, and soon enough the two families were able to put the two stories together. They speculated that maybe the cougar or some other terrifying creature had in fact put in an appearance, jumping the fence into the pasture and frightening the llamas. Llamas often freeze when frightened. But maybe a mother llama would behave more protectively, perhaps attempting to chase the intruder even after it left the pasture. And then, because she was so new to the neighborhood, she got lost and could not figure out her way back home.

The Smiths schemed to get her back. They'd bring her baby and some corral panels over to the Carne place and use the baby as a lure to arrange her capture.

At this point, oddly, the newspaper dropped the story. Did the plan work? Or is the llama still on the loose? We just don't know.

Perhaps it's worth noting that this is an old-media story. The Smiths and Carneses didn't tweet about the llama; they weren't brought together by Facebook status updates. But the Tuscaloosa News is letting us down here. We can only hope that now that the weekend is over and the football game is won, the journalists can get back to work and dig up the rest of the story.

Alabama

countryside

Cottondale

llama

(Image credit: Michelle Carter for the Tuscaloosa News)

Nov 24, 2011

This Thanksgiving Day we 99-percenters might as well be grateful for football, a blessing as mixed as any but as American as . . . never mind. The postcard pictured here is from 1900

This Thanksgiving Day we 99-percenters might as well be grateful for football, a blessing as mixed as any but as American as . . . never mind. The postcard pictured here is from 1900

In Maine, Deering and Portland high schools have been facing off in their annual Turkey Bowl since 1911; the forecast for this hundredth annual game calls for clear skies, temperatures just below freezing, and a Deering victory, though you never can tell.

In Alabama, college football starts getting serious this weekend as LSU contronts Arkansas and Alabama has to deal with Auburn; if these games go according to book, LSU and Alabama will meet at New Year's for the national title, in a rematch of an October game that just didn't go right at all for Alabama.

I suppose that only the very smallest families in America could possibly all dine together at the same Thanksgiving table; our table, like so many others, will be missing important people this year, for all sorts of reasons. But we'll be thinking of them, and probably making fun of them, and we'll raise a glass and eat cranberries and maybe later if it's not too cold, some of us will go out in the street and throw a football around, because it's a free country or something like that.

football

Alabama

Maine

Thanksgiving

Philadelphia

1900

holiday

Jan 19, 2012

Crazy weather in Alabama this winter, so warm and rainy that the daffodils burst into bloom in mid-January, about six weeks early. And then, of course, a cold front came crashing down; Anna Singer picked these blooms and got them into the house hours before the mercury fell to 23 degrees.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

flowers

daffodils

(Image credit: Anna Singer)

Mar 23, 2012

Last week, the Forest Lake homeowners' association in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, began siphoning the water out of Forest Lake, in hopes of revealing the debris that has collected in the lake since Tuscaloosa was devastated by a monster tornado eleven months ago.

Last week, the Forest Lake homeowners' association in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, began siphoning the water out of Forest Lake, in hopes of revealing the debris that has collected in the lake since Tuscaloosa was devastated by a monster tornado eleven months ago.

The lake sits in the geographic center of Tuscaloosa and was near the center of the tornado track. Virtually all the surrounding houses were destroyed, along with the trees that gave the neighborhood its name.

Yesterday, when the water had dropped to the level seen in this photo, engineers were able to make preliminary estimates of the cost of debris removal: just under $300,000, about 30% less than anticipated. Even though the lake is privately owned by the homeowners' association, the taxpayers will be paying for cleanup; the city hopes to share the cost with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resrouces Conservation Service.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Forest Lake

tornado

storm

debris

(Image credit: Chris Pow, al.com)

May 6, 2012

In 1946, a 23-year-old singer-songwriter named Hiram Williams, somewhat better known to the world as Hank Williams, performed with his band at the opening of a new Chevrolet dealership in Luverne, Alabama. That's him with the fiddle, an instrument he did not perform on very often.

In 1946, a 23-year-old singer-songwriter named Hiram Williams, somewhat better known to the world as Hank Williams, performed with his band at the opening of a new Chevrolet dealership in Luverne, Alabama. That's him with the fiddle, an instrument he did not perform on very often.

It was either the evening of this show in the Chevy parking lot, or the night of a street dance right around that same time, a fundraising dance sponsored by the Luverne volunteer fire department, when Hank Williams passed out drunk and had to be driven back home to Montgomery, an hour away. The designated driver was Howard Morgan, then captain of the Luverne fire department. "Hank Williams wasn't anything special in those days," Morgan recalled. "Just another cowboy singer."

Chevy dealership openings and volunteer fire department fundraisers were pretty much the only work Williams could get at that time; he'd been fired from his radio show for "habitual drunkenness," and a few months earlier he'd flunked his audition at the Grand Ole Opry. But he'd just made his first recording, which he may or may not have performed in Luverne that day: "Wealth Won't Save Your Soul."

His first record was a dud commercially, but by early 1947, with "Move It On Over," Hank Williams was on fire. During the next six years he wrote and recorded thirty songs, eleven of which made it to number one on the charts. His concerts all over the country drew thousands of adoring fans; never again would he have to perform in a Chevy dealership parking lot in Luverne, Alabama.

His final recording, a few weeks before his death on January 1, 1953, from abuse of alcohol, amphetamines, seconal, chloral hydrate, and morphine: "I'll Never Get Out of This World Alive."

On January 4, 1953, the city of Montgomery, Alabama, saw the largest crowd in its history gather to pay final respects to Hank Williams and to listen to Nashville stars performing his greatest hits. The funeral had to be moved to the city convention hall. Luverne volunteer fire chief Howard Morgan and his family were in Montgomery that day, stuck in traffic as the line of funeral-goers stretched for miles. Our friend Martha Morgan was two years old at the time, sitting in the backseat, too young to understand the occasion but definitely alert to the scene, to the sight of car after car after car after car; Hank Williams's farewell traffic jam became one of Martha's earliest childhood memories.

Alabama

music

Hank Williams

1946

Luverne

(Image credit: Alabama Department of Archives and History)

(h/t: Martha Morgan)

Jun 20, 2012

They say we could hit 100 today, or if not today then tomorrow. Which of course brings to mind the proverbial cold day in . . . Alabama, back in approximately 1989, when Forest Lake froze over solid and young Ted put on a scarf and a red hat and went out for an adventure on ice. You may be able to make out a dark blob just behind his left shoulder; that was a log we put out to set a limit on the adventure; beyond that point, we weren't sure how thin the ice might be, and Alabama kids didn't know from thin ice.

They say we could hit 100 today, or if not today then tomorrow. Which of course brings to mind the proverbial cold day in . . . Alabama, back in approximately 1989, when Forest Lake froze over solid and young Ted put on a scarf and a red hat and went out for an adventure on ice. You may be able to make out a dark blob just behind his left shoulder; that was a log we put out to set a limit on the adventure; beyond that point, we weren't sure how thin the ice might be, and Alabama kids didn't know from thin ice.

The thing about a cold day in Alabama is: if it's cold enough to freeze a lake, it's certainly cold enough to freeze everybody's plumbing, which is not insulated well enough to function in serious winter. We had an ax that we used to chop holes in that ice so we could get buckets of water to keep the toilet flushing.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

kids

Forest Lake

winter

Ted

ice

Dec 5, 2012

Music Pals For a Lifetime, by James Conner.

Music Pals For a Lifetime, by James Conner.

Conner grew up in rural Noxubee County, Mississippi, where he learned to draw from correspondence lessons off the back of a matchbook. He left Mississippi after high school, first for Vietnam and then for about twenty years in Detroit, where he worked as a police sketch artist. But the downward spiral of layoffs that was crushing Detroit eventually reached into the police force and claimed Conner's job.

He was devasted, he said, until he realized that losing his job meant he could finally go home. He'd been homesick his whole adult life, missing Mississippi.

He was no longer young by the time he got back home, but he married and started a family and went back to school, studying art at the University of Mississippi. He taught art for a while, then took the plunge and became a fulltime painter. He said he was trying to become the black Grandma Moses.

Like Grandma Moses, he is drawn to images from his rural childhood. He seems homesick still for his southern roots. But unlike Grandma Moses, Conner is a trained artist with a twenty-first-century eye, and he is a black artist, with a complicated relationship to southern experience.

In this painting and many others, young men carrying guitar cases venture out into the world. In some of the paintings, they travel, perform, try to make something of themselves. In some, they are headed back home again, for whatever reasons. In at least one of Conner's works, the man with the guitar is stuck in the crossroads. I like this picture; the guys with guitars have places to go, dreams to work out, and probably hard times ahead, but at least they've got each other.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Detroit

Mississippi

James Conner

Noxubee County

Jan 8, 2013

The Million Dollar Band has done it again–back-to-back national championships, three in the last four years. . . .

The Million Dollar Band has done it again–back-to-back national championships, three in the last four years. . . .

football

Alabama

Bama

Million Dollar Band

Roll Tide

Feb 10, 2013

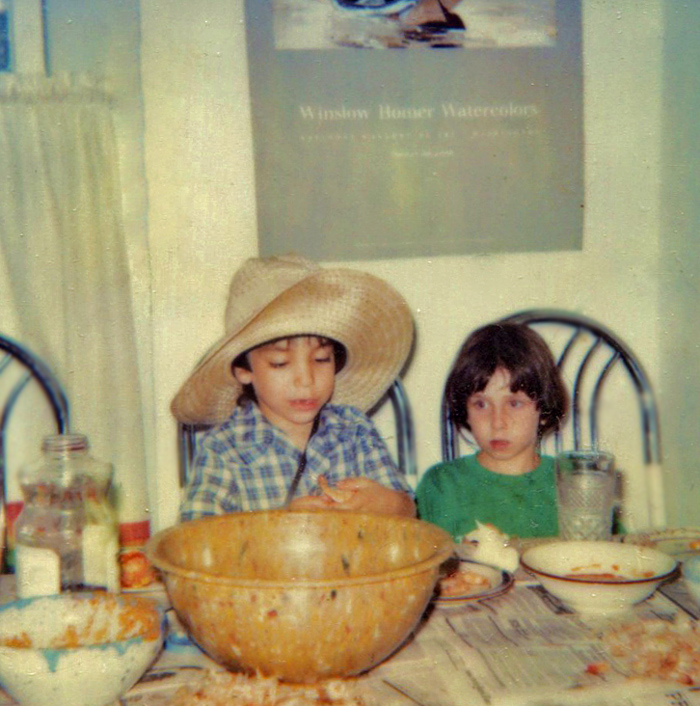

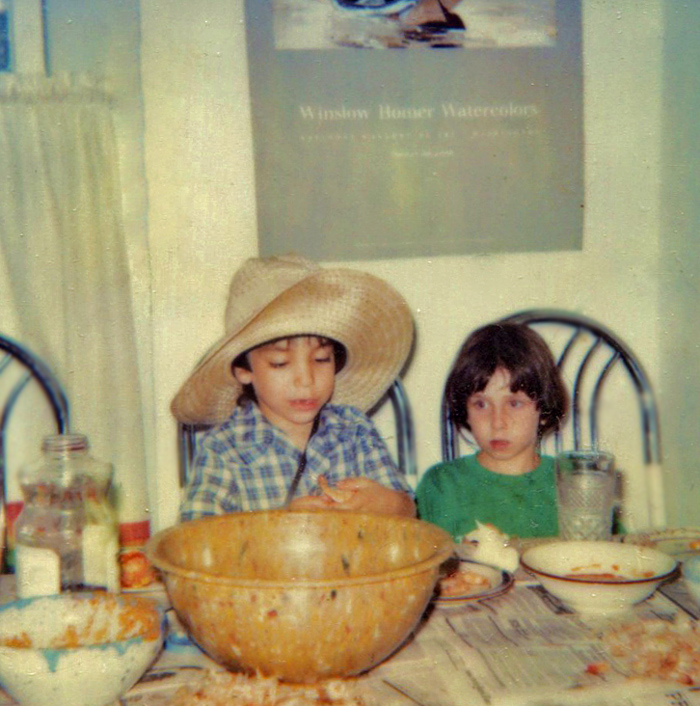

Shown here in a curled-up polaroid snapshot from a nightstand drawer, eating shrimp on a kitchen table covered with newspaper, probably in 1985 or 1986, back when they were shrimpy little kids and pretty good friends, are Joe Stein and Stephanie Jacobs.

Shown here in a curled-up polaroid snapshot from a nightstand drawer, eating shrimp on a kitchen table covered with newspaper, probably in 1985 or 1986, back when they were shrimpy little kids and pretty good friends, are Joe Stein and Stephanie Jacobs.

Stephanie and Joe went to preschool together and then to University Place Elementary, and for many years they went to the same after-school program and the same Sunday school.

Based on this picture, we might guess that Stephanie liked milk with her shrimp, or else liked milk but not shrimp, or perhaps liked neither but had been told to drink her milk.

Joe appears to be a serious shrimp-peeler, despite wearing an obviously unserious sort of hat.

Both Stephanie and Joe have gone back to school in recent years at the University of Alabama, Stephanie for a library science master's in book arts and Joe for a music degree in piano performance.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Joe

Stephanie

1985?

1701 5th Avenue

kitchen table

Polaroid

May 4, 2013

Friends live here, on a bluff above Canyon Lake in Cottondale, Alabama.

Friends live here, on a bluff above Canyon Lake in Cottondale, Alabama.

Alabama

landscape

waterscape

Cottondale

Martha

porch

Canyon Lake

Mike

May 28, 2013

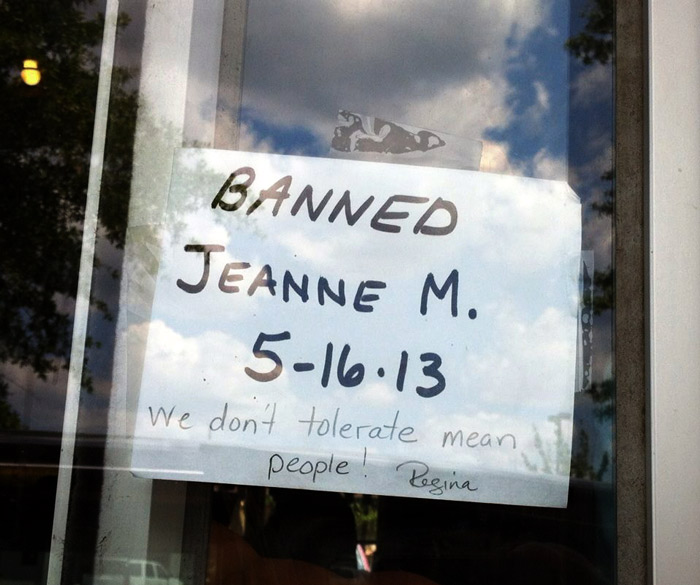

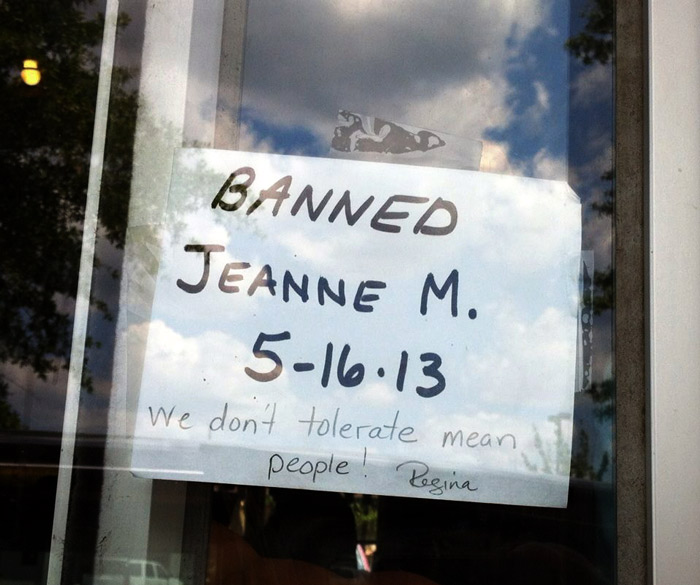

Regina's, we're told, is a restaurant in Mobile, Alabama. We don't know what you have to do to get yourself declared intolerably mean and banned from there. And we don't know Jeanne M., which is probably okay.

Regina's, we're told, is a restaurant in Mobile, Alabama. We don't know what you have to do to get yourself declared intolerably mean and banned from there. And we don't know Jeanne M., which is probably okay.

Alabama

signage

Mobile

Regina's

(Image credit: Cathy Collins)

Sep 26, 2013

We're told the egg may hatch soon. Watch this space for updates.

We're told the egg may hatch soon. Watch this space for updates.

Alabama

garden

bird

yardscape

sticks

Mobile

nest

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Oct 16, 2013

Alabama

window

signage

Mobile

(h/t: CC)

stained glass

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Nov 30, 2013

Juniper Self, shown here with her mother Daphne, came dressed to cheer at Bryant-Denny Stadium last week for her first Alabama football game. The Crimson Tide beat University of Tennessee–Chattanooga, 49–0.

Juniper Self, shown here with her mother Daphne, came dressed to cheer at Bryant-Denny Stadium last week for her first Alabama football game. The Crimson Tide beat University of Tennessee–Chattanooga, 49–0.

Today's Iron Bowl game at Auburn is for all the marbles. Roll Tide Roll.

Tuscaloosa

sports

football

Alabama

Daphne

cheerleader

Juniper

(h/t: Scott Self)

Apr 8, 2014

Lots of weather delays Sunday at the Birmingham airport.

Lots of weather delays Sunday at the Birmingham airport.

Alabama

portrait

airport

orange

sport

Birmingham

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Apr 10, 2014

By eleven o'clock on a Friday night, the streets of downtown Bessemer, Alabama, are empty, and the town looks dead. Even the Bright Star Restaurant is closed for the night.

By eleven o'clock on a Friday night, the streets of downtown Bessemer, Alabama, are empty, and the town looks dead. Even the Bright Star Restaurant is closed for the night.

The only thing open, it seems, at least on this block of 19th Street in Bessemer, is the office of Liberty Tax preparers. Wonder why the folks in there are burning the midnight oil?

Alabama

night

streetscape

tax

Bessemer

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Aug 21, 2014

At the Waysider in Tuscaloosa, where another semester and another football season are already so close you can taste them.

At the Waysider in Tuscaloosa, where another semester and another football season are already so close you can taste them.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

food

restaurant

couple

Waysider

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Nov 1, 2014

Back in the '80s, when Kelley was a little girl growing up in Mobile, Alabama, the camera caught up with her and her giagia (yaya) as they settled down into the couch for a game of chess.

Back in the '80s, when Kelley was a little girl growing up in Mobile, Alabama, the camera caught up with her and her giagia (yaya) as they settled down into the couch for a game of chess.

We are told that Kelley turns 36 this month. Her giagia, Coula, lived to the age of 95, long enough to get to know her great-grandson, Kelley's son Thomas.

Is there anything more adorable than a grandmother-granddaughter chess match? Let's not overthink that. It's perfect.

Alabama

chess

Mobile

couch

sofa

grandmother

grandchild

(h/t: Tina L)

Nov 29, 2014

Stars fall on Alabama. In song, in meme, in license-tag slogan, in life and in legend. What follows is a long story about a good star and a bad star that fell on Alabama after lunch one day, out of a clear blue sky, sixty years ago this week.

Stars fall on Alabama. In song, in meme, in license-tag slogan, in life and in legend. What follows is a long story about a good star and a bad star that fell on Alabama after lunch one day, out of a clear blue sky, sixty years ago this week.

One of the stars would bring a little good fortune into the life of a poor farm family in the east-central part of the state. The other would bring fifteen minutes of fame and a whole lot of grief to a neighboring family, a husband and wife who were living, appropriately enough, across the road from the Comet Drive-In Theater.

The story of the good star was written up at the time in Ebony magazine. The story of the bad star was on TV and in all the newspapers, as well as Life magazine and National Geographic. That was the way it was.

Technically speaking, of course, the two stars were not stars at all; they were pieces of rock–meteorites–chips off of a meteoroid that had traveled millions of miles through the solar system before entering Alabama airspace. The meteoroid's orbital path had been much larger than, and at odds with, the earth's. Because it smashed into the sunlit side of earth near midday, it must have been headed away from the sun at the time. Astronomers calculate its likely origin as an asteroid they call 1685 Toro.

But that November afternoon, when the stars were falling on Alabama–when a bright white fireball and bone-jarring explosions were shattering the sky–nobody was thinking meteorites. They were thinking Soviet attack. Maybe an airplane was exploding, possibly because of flying saucers but more likely because of Russians. The U.S. Air Force base at Maxwell Field, near Montgomery, Alabama, was alerted to search for airplane wreckage and to protect Alabama from Soviet aggression.

The explosions and fireball had been generated when the meteoroid, traveling at about 30,000 miles per hour through empty space, suddenly impacted the top of the earth's atmosphere. The friction from air molecules vaporized most of the rock, blasted and charred the bits that remained, and slowed down the flight to a few hundred miles per hour.

It is estimated that for any significant fragments of a meteoroid to survive the flaming 40-second journey down through the atmosphere, the original size must be quite large, at least 150 pounds. The two known surviving chunks of this one weighed in at about 8 pounds and 3.5 pounds.

The smaller chunk fell onto a dirt road in the rural community of Oak Grove, five miles northwest of the town of Sylacauga. Late in the afternoon, it was spotted by a team of mules pulling a wagonload of firewood. The mules shied at the rock in the road, perhaps because it smelled of sulfur. Julius McKinney, the farmer who was driving the wagon, could not convince his mules to move on; figuring that they'd encountered a snake, he grabbed a stick of the firewood and climbed down into the road.

But it was only a black rock. McKinney tossed it off into the weeds at the side of the road and went on home.

By the next day, the other star that had fallen on Alabama from that meteoroid was the talk of the town. The other black rock had landed a couple of miles away from the one found by McKinney's mules; almost immediately, it had been confiscated by the police, who had locked it up for safekeeping and then turned it over to the air force.

But first, the police had brought it to a nearby gravel pit, where a state geologist, George Swindel, happened to be working that day on a groundwater survey; Swindel suspected it was just a piece of the local limestone, but after consulting his reference books he tested a chipped surface with a drop of acid. The rock didn't bubble the way limestone would, but it did emit a rotten-egg odor, the way a meteorite might. Swindel also noted a charred "crust" and numerous "thumbprint" indentations in the surface, two characteristic features of rocks that have made a fiery, turbulent plunge through the atmosphere.

Swindel's identification of the object as a meteorite changed the thrust of public conversation–forget about the Cold War; the space age had arrived in Sylacauga. Even though there was no such thing yet as an official, government-sponsored space age, people around town knew that this rock from outer space had put them on the map.

And the scent of money was in the air. There is a worldwide market for meteorites, with collectors and traders and speculators and scientific organizations all competing for the same few pieces of rock. Prices were rumored to be . . . astronomical, of course.

Based on all the gossip about the meteorite that Swindel had tested, Julius McKinney suspected that his mules had located a piece of the same stuff. He went back to the spot, found it in the underbrush, and carried it home.

But now what? McKinney wasn't sure what, if anything, his meteorite was worth, but he was sure of one thing: he'd never see a dime from it unless he found a white man to represent him, to make inquiries and pursue negotiations.

The only white man he trusted was the postman. McKinney turned the rock over to him.

Meanwhile, the other chunk of meteorite had the town in an uproar, and for good reason. Instead of showing up quietly on a lonesome country road, this other one had arrived in Alabama with a spectacular flourish.

It had hit the roof of a 140-year-old frame house along the Birmingham highway about three miles northwest of Sylacauga. God had willed it to go there, some said, because of the Comet Drive-In Theater across the street.

The meteorite had penetrated the asphalt shingles and wooden roof decking atop the house, grazed a rafter and joist in the attic, and burst through the three-quarter-inch tongue-in-groove wooden ceiling.

In the living room, it had smacked down onto a large Philco radio console, fracturing the laminated wood of the cabinet. The radio deflected the rock's trajectory, ricocheting it across the room, to the sofa where Ann Hodges lay wrapped in two quilts, trying to take a nap.

The rock hit her hard, severely bruising her left wrist and hip. And with that blow, Hodges became the only human being in modern times to take a direct hit from outer space.

There have been vague tales of similar occurrences in ancient and medieval days, but the names of no other victims have come down to us. And even today, sixty years later, Hodges's story is still a singular one; last year, people in Siberia were injured by flying glass from a meteorite-induced sonic boom, but no one other than Ann Hodges is known to have been actually touched by a falling star.

Hodges's mother, who was sewing in the next room, called the police. The women assumed something in the house must have exploded. Maybe the heater? Could the black thing be part of some machine? The first officer on the scene, Sylacauga's police chief W.D. Ashcraft, had been an eyewitness that afternoon to the pyrotechnics in the upper atmosphere–"like a gigantic welding arc," he said–and he had his own theories about the rock. It must be part of an airplane, he figured, or else part of a bomb that had made an airplane explode. It looked pretty plain and simple for any of that, however. He wondered if airplanes carried rocks for ballast, the way ships do?

Chief Ashcraft called for backup from the air force, which sent a helicopter carrying a couple of officers from Maxwell Field. The copter landed on the lawn in front of the high school, where the chief met the officers and showed them the rock. They were able to dismiss it immediately as unrelated to any aircraft, and they were also able to report that no planes were unaccounted for that day.

A helicopter at the high school, plus a mysterious black rock, plus a hole in the house across from the Comet Drive-In, plus whatever it was that had happened to Ann Hodges–this was one welding arc in the sky that had left Sylacauga in something of an uproar. Although Hodges's injuries were not severe, they were uncomfortable, and she was shaken and flustered and more than a little upset, both by what had happened to her and by the commotion. People were peeking in her windows and crowding her front door, straining to see the damage. Radio and newspaper reporters were hounding her for interviews. She was said to be a shy woman and prone to nervousness. The police said she begged them to make everybody go away, and so they whisked her off to the hospital, as much for privacy as for medical attention.

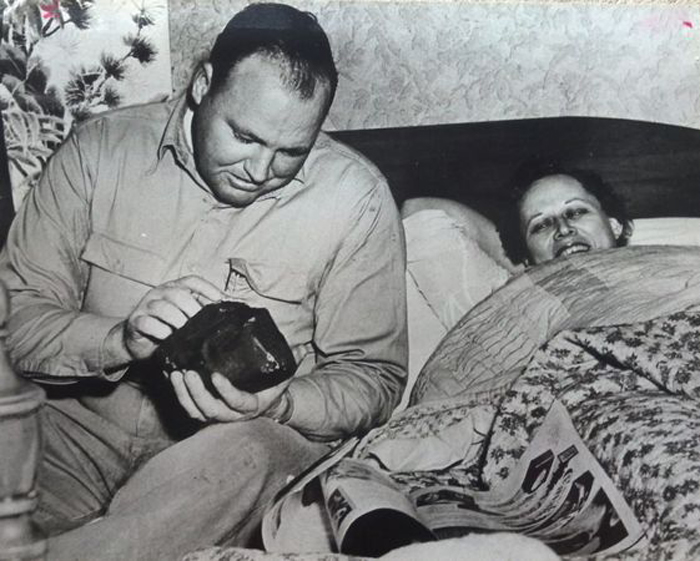

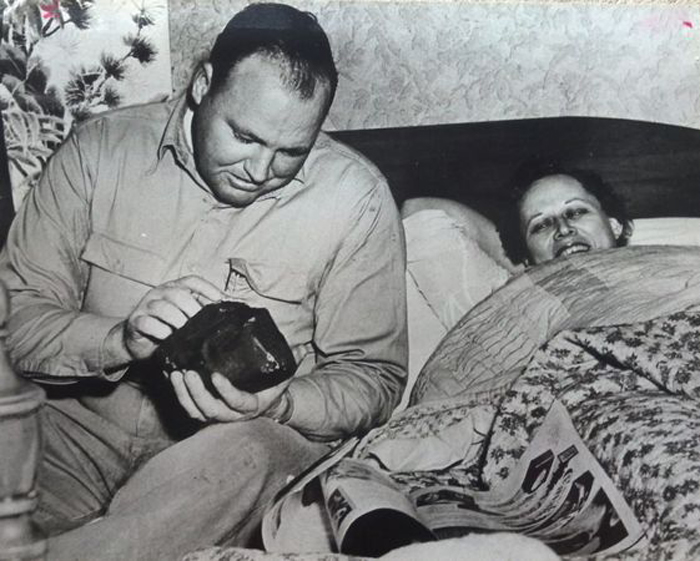

That evening, when her husband Eugene came home from work–he was a crew boss for a utility contractor, setting poles and clearing brush from the right-of-way–he found such a crowd on his front porch that he had to shove people aside to open the door. Inside, he found the hole in the ceiling, but both the rock and his wife had disappeared. Ann Hodges was hospitalized for five days, which was plenty long enough for the doctor to pose for a newspaper photographer while rearranging Hodges' clothing to reveal the nasty-looking bruise on her thigh. She averted her eyes awkwardly.

Meanwhile, the air force had whisked the rock off to its lab in Ohio "for further study." And the Hodgeses, who had quickly been made aware of the meteorite's potential monetary value, wanted it back. "I feel like the meteorite is mine," Ann Hodges told reporters. "I think God intended it for me. After all, it hit me."

God's intentions aside, the meteorite wasn't clearly hers. The public thought it was, but the way the law triangulates these things, rocks and minerals that show up naturally on private property belong not to the finder but to the owner of the property. Ann and Eugene Hodges didn't own the house they were living in at the time; they rented it from a woman named Birdie Guy, who was recently widowed and apparently quite anxious about her finances.

Guy quickly came forward to make her claim in the media. The meteorite was hers, she said, and she needed it badly; she was strapped for cash and would have to sell it to raise money to fix the damaged house.

Guy and the Hodgeses argued back and forth in the newspapers and on TV, and then they all lawyered up and filed suit.

Julius McKinney's rock, in the meantime, sat quietly with the postman, who had conducted a little discreet research into the meteorite market and had made contact with a few potential customers and agents, including a lawyer in Indianapolis who would represent McKinney in commercial negotiations. But in the early days of the meteorite frenzy, while the furor raged over the Hodgeses' piece of the rock, McKinney and the postman kept their secret.

Ann Hodges was taken to New York to appear on national TV. Back at home, she and her husband posed in bed with the rock for photographers from Life magazine. They may have made a little money off their notoriety, but they had lawyers to pay. It took them two years to get the landlady's lawsuit off their backs, which they finally did by paying her $500 to drop her claim.

By then, all those eager meteorite-buyers that the Hodgeses had been dreaming about were nowhere to be found. The legal fuss had left some potential customers reluctant to get involved with such litigious sellers. And public attention had moved on; even in Sylacauga, people were no longer particularly interested in that rock. The Hodgeses couldn't find a soul willing to pay good money for it.

They'd gotten one offer, back in the beginning, from a representative of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. They had dismissed it then as ridiculously low. But now that title was finally clear and they could go ahead and sell the thing, they discovered that the Smithsonian was no longer interested.

Why? Because the museum had already purchased the McKinney chunk of the Sylacauga meteorite.

For how much? The price has never been made public, but it is reported that after the sale, McKinney and his family bought a house and a car and possibly also ten acres of farmland.

The Hodgeses finally gave their rock away. In 1956, they donated it to the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa, where generations of schoolchildren have made it by far the most popular exhibit in the museum.

It is said that Ann Hodges never fully recovered from all that fell on her that day from out of the clear blue sky: not just her injuries, but the unwelcome attention, the media manipulation, and the stress and expense of the protracted legal battle, with its disappointing outcome.

Within a few years, she was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown. Her marriage ended. She became a recluse and an invalid. Sixteen years after being touched by a star, she died of kidney failure. She was 52 years old.

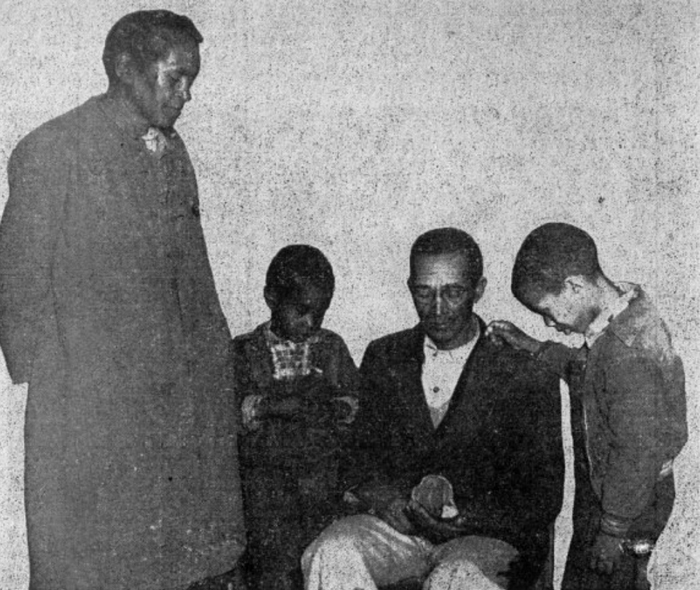

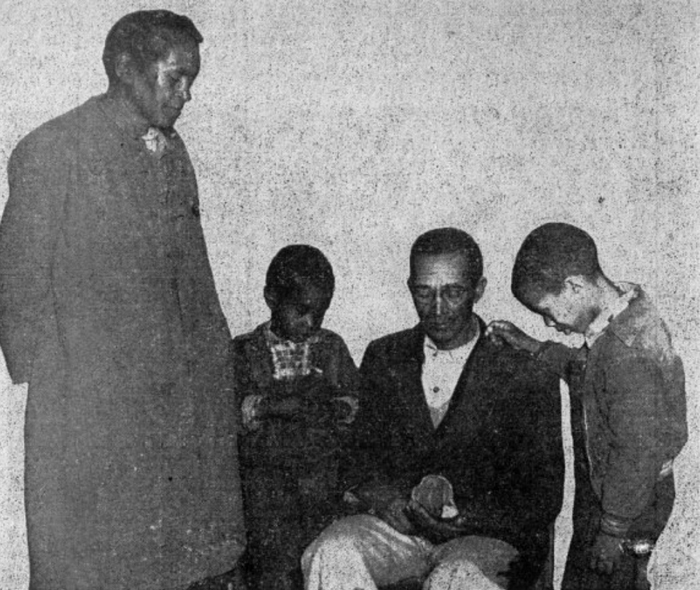

Julius Kempis McKinney was already older than that on the day he found his chunk of the meteorite; his date of birth is not recorded but is believed to be approximately 1897. He had joined the army in 1917 and fought in World War I. When he and his wife, Callie O'Neal McKinney, posed with the meteorite for a photographer from Ebony magazine, they included two of their grandsons in the picture.

A thin slice from his piece of the rock has been examined under a microscope by Smithsonian geologists, who were able to classify it as an H4 chondrite, one of the most common types of meteorites. It contains so much iron that it will deflect a compass needle by a degree or two. It also contains spherical crystals, which form only when mineral crystallization occurs in weightless outer space.

Meteorites are the oldest rocks ever found. Almost all of them are close to five billion years old, dating back to the early days of the solar system, when collisions between what we might call baby planets sometimes ejected chunks of planetary matter into wild and crazy orbits.

These rocks can fly through space for billions of years, it seems, but the minute they fall on Alabama, they make a ruckus.

Alabama

1954

Oak Grove

meteorite

Sylacauga

Feb 10, 2016

This is the earliest known photo of all five boys, taken at Forest Lake, Tuscaloosa, in November or December of 1992.

This is the earliest known photo of all five boys, taken at Forest Lake, Tuscaloosa, in November or December of 1992.

For what it's worth, all the trees in the background are gone now, shredded by the tornado in 2011. The boys, however, are still going strong: from left to right, there's Joe, now 34; Allen, 27; Ted, 36; John, who just turned 38; and bobble-headed newborn Hank, who's now 23.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

sunset

John

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

boys

Steins

Mar 17, 2016

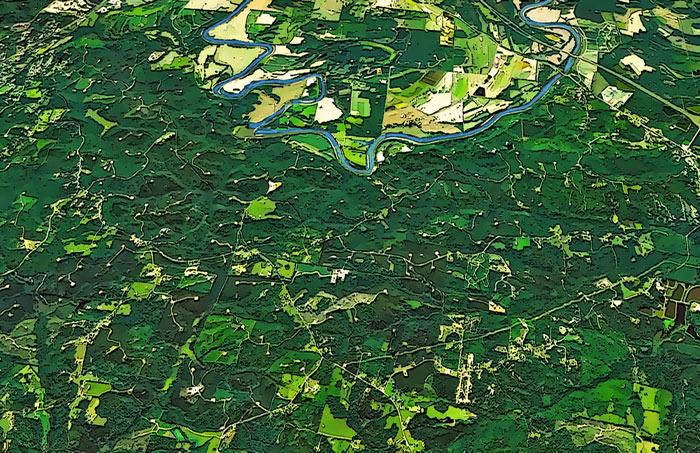

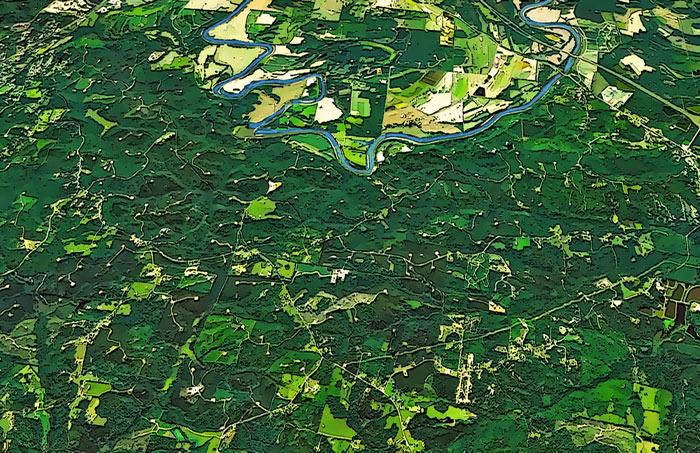

Southwest of Tuscaloosa, near the small town of Moundville, Alabama, the meandering Black Warrior River twists and turns through mostly forested countryside. In this rendering based on satellite imagery, there are little white dots scattered everywhere in the trees and the fields; each dot is at the end of a little spur of road.

Southwest of Tuscaloosa, near the small town of Moundville, Alabama, the meandering Black Warrior River twists and turns through mostly forested countryside. In this rendering based on satellite imagery, there are little white dots scattered everywhere in the trees and the fields; each dot is at the end of a little spur of road.

These are drilling pads for methane wells.

Methane is the gas that sickens canaries in coal mines. It's what all too frequently makes underground mines explode; wherever there's coal, there's methane. Commercial extraction of coalbed methane, to be sold as natural gas, began in the early 1980s, and the Warrior basin of Alabama was scene of the world's first methane boom; to maximize production quickly, wells were drilled every few hundred feet throughout the region.

After a very few years, the boom went bust. Most wells now sit idle, and many have been orphaned, leaving the cleanup and decommissioning expenses to the taxpayers.

But you can still see the little white dots on the landscape, even from space.

Alabama

methane

Black Warrior River

coalbed

drilling rigs

meanders

Moundville

Jan 5, 2017

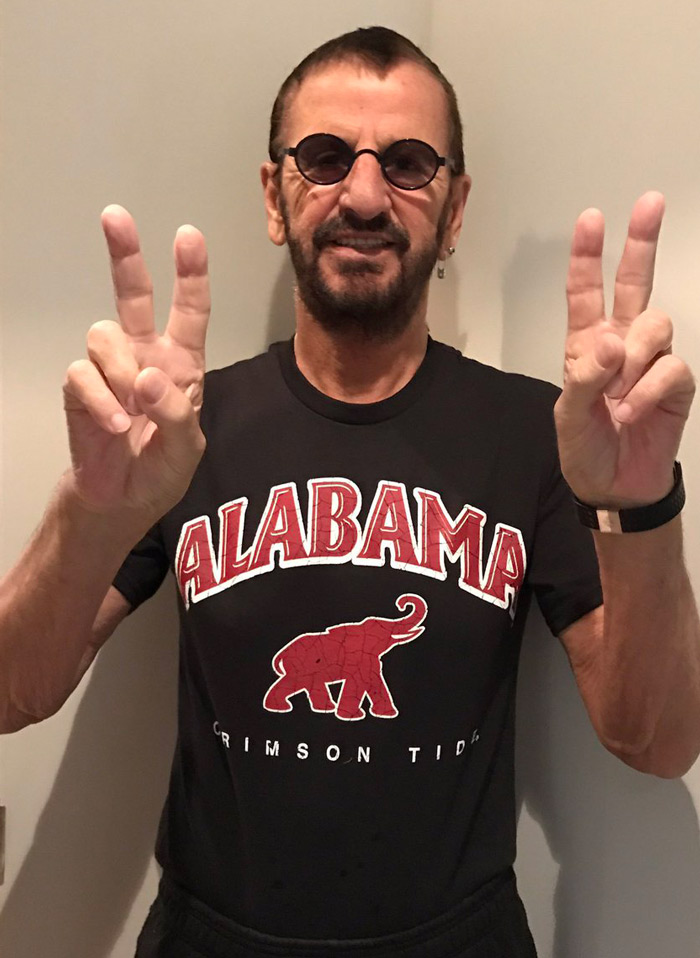

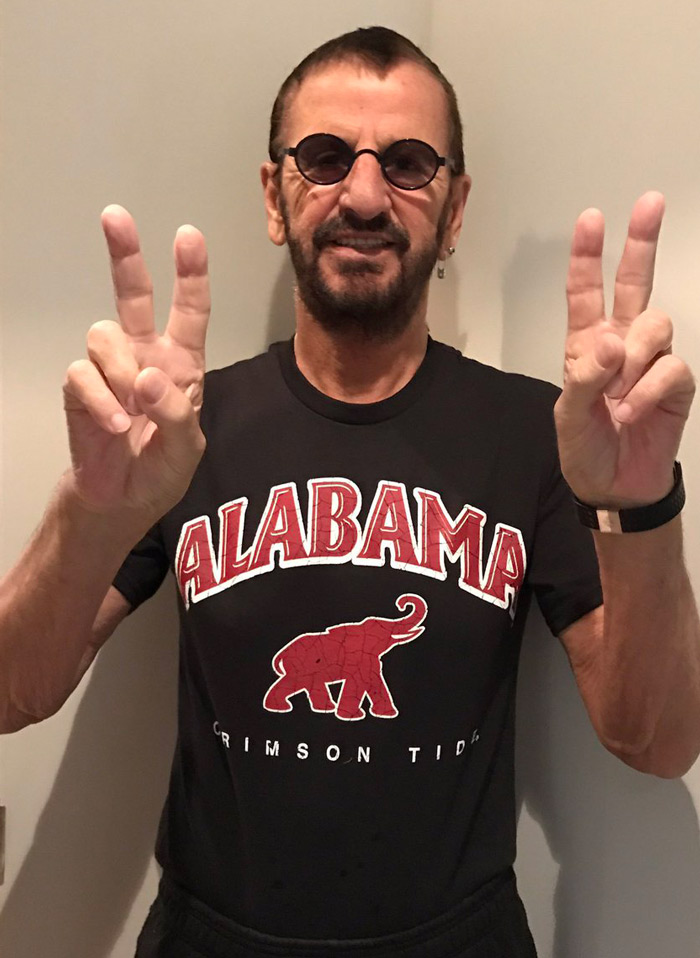

After Alabama won the Peach Bowl last Saturday, Ringo Starr apparently tweeted this picture of himself, along with the text "Roll Tide peace and love."

After Alabama won the Peach Bowl last Saturday, Ringo Starr apparently tweeted this picture of himself, along with the text "Roll Tide peace and love."

Ringo has been a Bama fan for thirty years now, thanks to his friendship with Fred Nall Hollis, a multimedia artist from south Alabama who uses the single name Nall professionally. The two met in 1986, when Nall rented a house he owned in the south of France to Ringo and his wife, Barbara Bach. They got to talking about the artwork hanging in the house, and then Ringo asked Nall if he would teach him how to draw and paint.

The art lessons continued off and on through the 1980s and '90s, and in recent years Ringo has launched an art career of his own, working in digital media.

Nall has painted two portraits of Ringo, who has become active in the work of Nall's foundation. The foundation focuses on helping artists and art students recover from addiction and create new sober, artistically vital lives for themselves.

One of Ringo's drumsticks sits among the paintbrushes in Nall's Fairhope studio.

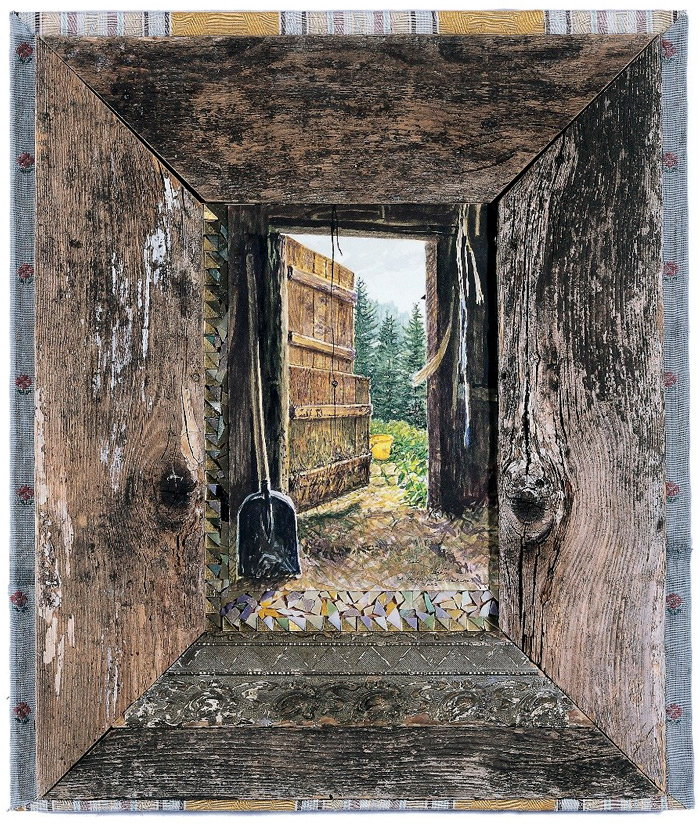

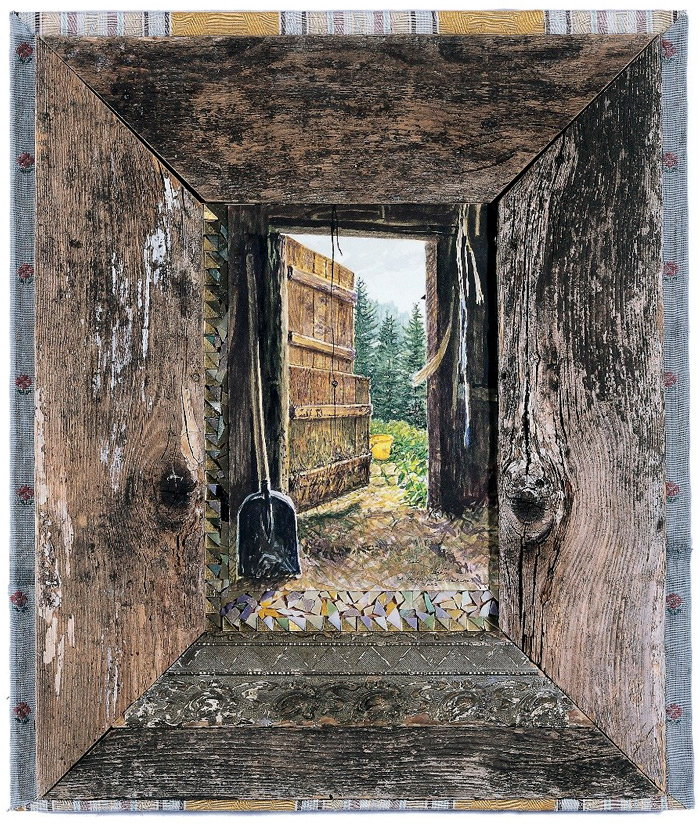

The picture below, "Inside the Barn," is a recent creation by Nall.

For those among us who haven't been paying attention, the Crimson Tide face off against Clemson next Monday for the national championship. Peace and Love!

football

Alabama

painting

art

Crimson Tide

Ringo Starr

Fred Nall Hollis

Jan 8, 2017

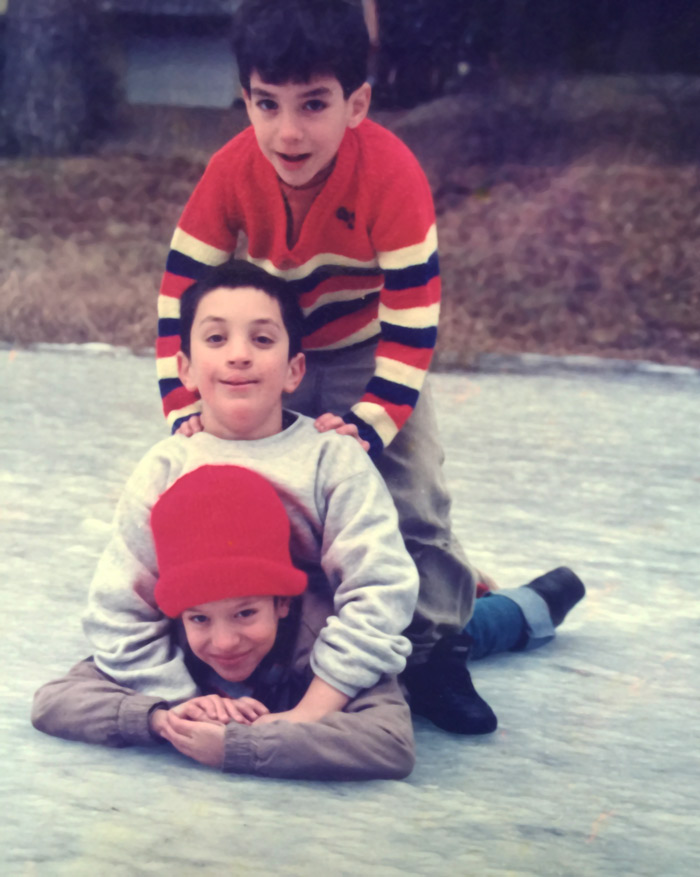

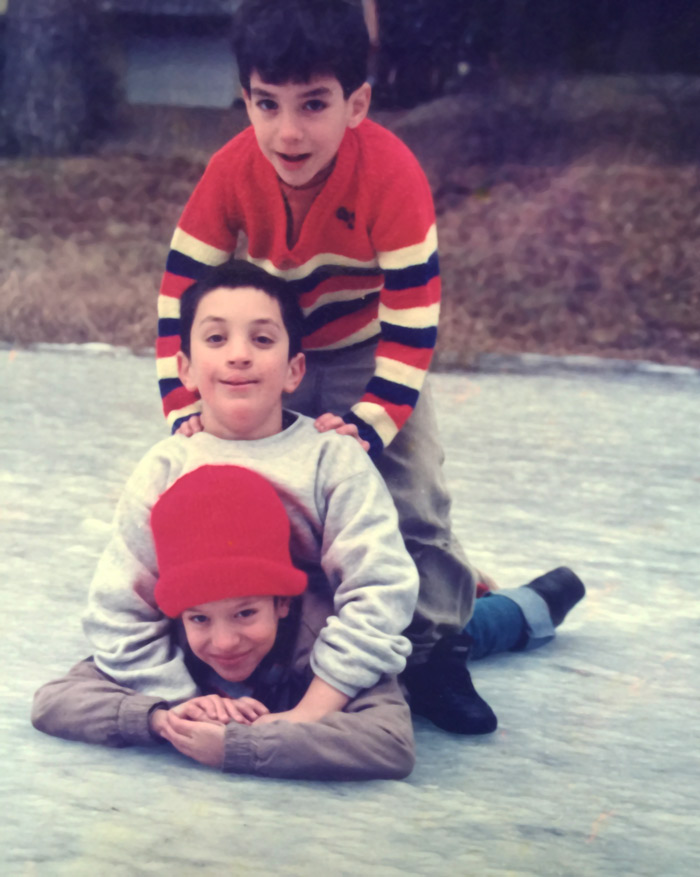

Snow fell on Alabama the other day, and bitter cold settled in. Same thing happened there back in about 1989, when Forest Lake in Tuscaloosa froze up thick enough to run around and slide on, and our three eldest posed for a picture on the ice.

Snow fell on Alabama the other day, and bitter cold settled in. Same thing happened there back in about 1989, when Forest Lake in Tuscaloosa froze up thick enough to run around and slide on, and our three eldest posed for a picture on the ice.

From the bottom: Ted, John, Joe. Note the complete absence of gloves or mittens, and the general inadequacy of winter apparel. In his hat and jacket, Ted appeared to have a chance of staying warm, but the other two just had to tough it out. There is no evidence in this picture of the socks-on-the-hands and/or plastic-bags-in-the-shoes that we recall improvising for wintry moments in Alabama; nonetheless, they all somehow survived.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Forest Lake

brothers

winter

John

Joe

Ted

ice

(Image credit: old family snap)

Feb 26, 2017

Joe and his friend Beau pose for a picture last spring in Beau's new food truck, Local Roots, which plies the streets of Tuscaloosa serving an international menu that features locally grown foods.

Joe and his friend Beau pose for a picture last spring in Beau's new food truck, Local Roots, which plies the streets of Tuscaloosa serving an international menu that features locally grown foods.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

food

Joe Stein

work

restaurant

food truck

Beau Burroughs

(Image credit: the phone)

Feb 28, 2017

After 15 years of service in a city fire department, which likely involved one or more calls a day, every day, round the clock, round the year, a fire engine is pretty well beat up.

After 15 years of service in a city fire department, which likely involved one or more calls a day, every day, round the clock, round the year, a fire engine is pretty well beat up.

If it's well worn but not completely used up at that point, it goes into the city's reserve fleet, to replace newer equipment that's out of service for repairs or maintenance.

After 5 or so years of reserve duty, it's surplus; maintenance at that point is costly, and there is newer equipment falling into reserve status.

So 20-year-old firetrucks go on the market, at a steep discount, and the purchasers typically are small, volunteer fire departments, which could never afford the $500,000 or more needed to buy a new pumper vehicle.

The duty level expected of the old truck isn't nearly as heavy with a volunteer force, where it might be called out for fires only a few times a year instead of several times a day.

The fire engine pictured here was bought new by the Tuscaloosa City Fire Department in 1984; twenty years later, it was sold to the Sapps–Union Chapel Volunteer Fire Department in nearby Pickens County, which is still using it in 2017 and plans to keep running it forever.

Posing with it are Assistant Chief Troy Jordan and Fire Chief Pauline Hall.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Troy Jordan

Pickens County

1984 model

fire engine

Sapps–Union Chapel Volunteer Fire Department

Pauline Hall

(Image credit: Gary Cosby Jr. for the Tuscaloosa News)

This Thanksgiving Day we 99-percenters might as well be grateful for football, a blessing as mixed as any but as American as . . . never mind. The postcard pictured here is from 1900

This Thanksgiving Day we 99-percenters might as well be grateful for football, a blessing as mixed as any but as American as . . . never mind. The postcard pictured here is from 1900

In 1946, a 23-year-old singer-songwriter named Hiram Williams, somewhat better known to the world as Hank Williams, performed with his band at the opening of a new Chevrolet dealership in Luverne, Alabama. That's him with the fiddle, an instrument he did not perform on very often.

In 1946, a 23-year-old singer-songwriter named Hiram Williams, somewhat better known to the world as Hank Williams, performed with his band at the opening of a new Chevrolet dealership in Luverne, Alabama. That's him with the fiddle, an instrument he did not perform on very often.

Music Pals For a Lifetime, by James Conner.

Music Pals For a Lifetime, by James Conner.

Shown here in a curled-up polaroid snapshot from a nightstand drawer, eating shrimp on a kitchen table covered with newspaper, probably in 1985 or 1986, back when they were shrimpy little kids and pretty good friends, are Joe Stein and Stephanie Jacobs.

Shown here in a curled-up polaroid snapshot from a nightstand drawer, eating shrimp on a kitchen table covered with newspaper, probably in 1985 or 1986, back when they were shrimpy little kids and pretty good friends, are Joe Stein and Stephanie Jacobs.

Regina's, we're told, is a restaurant in Mobile, Alabama. We don't know what you have to do to get yourself declared intolerably mean and banned from there. And we don't know Jeanne M., which is probably okay.

Regina's, we're told, is a restaurant in Mobile, Alabama. We don't know what you have to do to get yourself declared intolerably mean and banned from there. And we don't know Jeanne M., which is probably okay.

Juniper Self, shown here with her mother Daphne, came dressed to cheer at Bryant-Denny Stadium last week for her first Alabama football game. The Crimson Tide beat University of Tennessee–Chattanooga, 49–0.

Juniper Self, shown here with her mother Daphne, came dressed to cheer at Bryant-Denny Stadium last week for her first Alabama football game. The Crimson Tide beat University of Tennessee–Chattanooga, 49–0.