Hole in the Clouds

Jan 5, 2010

All five Stein boys touched down in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, a few days ago and claimed the beachhead for the Crimson Tide. That's not very hard to do in Tuscaloosa.

The occasion was the premier social event of the year, on New Year's Day, the wedding of Neely Sims and Damon Ray.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

night

Crimson Tide

John

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

Feb 10, 2011

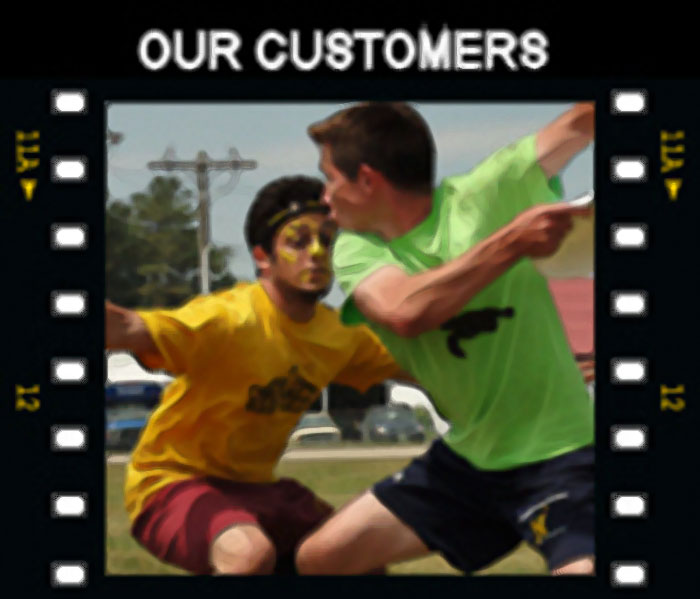

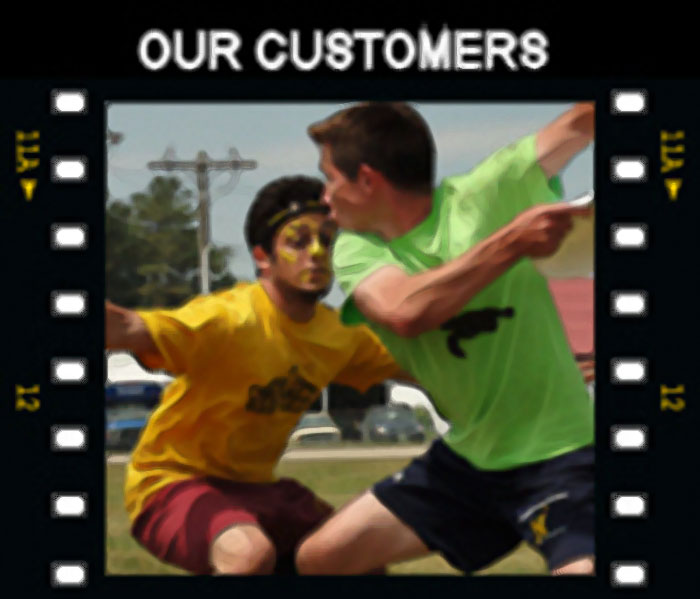

Hank, in yellow, was the "customer" of a company that embroiders custom designs, such as team logos, onto anything you can think of--in this case, a Rumblebee! embroidered on a headband. The Rumblebees played ultimate frisbee last summer in a county league. Recently, Hank noticed that the embroidery company was offering discounts and other rewards in return for customer photos of the embroidered items in action. He sent them this photo, and they sent him fifty dollars and put his picture onto the front page of their website.

Hank, in yellow, was the "customer" of a company that embroiders custom designs, such as team logos, onto anything you can think of--in this case, a Rumblebee! embroidered on a headband. The Rumblebees played ultimate frisbee last summer in a county league. Recently, Hank noticed that the embroidery company was offering discounts and other rewards in return for customer photos of the embroidered items in action. He sent them this photo, and they sent him fifty dollars and put his picture onto the front page of their website.

Hole-in-the-Clouds, of course, endorses nothin', embroidered or otherwise. But I can't help but feel a warm spot in my heart for any company that concludes that featuring the image of one of my children will be good for business. Especially if they offer to pay for my child's image. So I'll drop my scruples down around my ankles and share the link.

Yes, Hank's face was painted yellow--something to do with team spirit. And yes, right after the picture was snapped, the guy in green punched Hank in the face as he sent the frisbee flying. It was not intentional, sez Hank. The guy is a nice kid, a former high school wrestler who is currently attending Maine Maritime Academy. They may meet again next summer, faces painted, headbands embroidered, ready for Ultimate combat. Go, Rumblebees!

sports

Hank

ultimate frisbee

headband

marketing

Apr 28, 2011

Hank swings his way up the wall in the climbing gym. Rock climbing has become a passion of his lately, but he says that climbing in a gym is not nearly as pleasant and exciting as climbing cliffs and boulders outdoors in the fresh air.

Hank swings his way up the wall in the climbing gym. Rock climbing has become a passion of his lately, but he says that climbing in a gym is not nearly as pleasant and exciting as climbing cliffs and boulders outdoors in the fresh air.

sports

Hank

gym

rock climbing

(Image credit: S.A. Stein)

Jun 22, 2011

Rarely do we get to say good morning to the folks in one of these pictures while they are still there, where they are pictured, in real time.

Rarely do we get to say good morning to the folks in one of these pictures while they are still there, where they are pictured, in real time.

Allen just sent this phoneshot of Hank stirring the embers at their campsite in the sandhills of western Nebraska. The boys are westward bound, crossing the country from Maine to Seattle via Colorado. Wednesday morning, they'll wake up here at the lake, break camp, and hit the highway, aiming straight for the Rocky Mountains.

landscape

camping

Hank

Nebraska

lake

road trip

(Image credit: S.A.S.)

Sep 21, 2011

Stein boys doing their brotherly whatever on the street last summer in Seattle. From the bottom: brothers number 4, 1, and 5.

Stein boys doing their brotherly whatever on the street last summer in Seattle. From the bottom: brothers number 4, 1, and 5.

Washington

brothers

streetscape

John

Allen

Hank

Seattle

(Image credit: Bonnie Strelitz)

Nov 14, 2011

They're up to something.

They're up to something.

Hank

Philadelphia

kitchen

boys

JJ

Steins

Jan 14, 2012

Bunch a guys were off climbing last week in Red Rock Canyon, a few miles west of Las Vegas, Nevada. Here, Hank leads the route, carefully placing little thingamajigs in cracks to hold the rope so other climbers can follow him safely. As lead climber, Hank is roped in, but not quite as safely as the followers; if he loses his grip on the rock, the thingamabobs below him should arrest his fall (with the help of the belayer down on the ground), but before they do, he could expect to fall twice the distance down to the topmost thingamabob. He didn't fall.

Bunch a guys were off climbing last week in Red Rock Canyon, a few miles west of Las Vegas, Nevada. Here, Hank leads the route, carefully placing little thingamajigs in cracks to hold the rope so other climbers can follow him safely. As lead climber, Hank is roped in, but not quite as safely as the followers; if he loses his grip on the rock, the thingamabobs below him should arrest his fall (with the help of the belayer down on the ground), but before they do, he could expect to fall twice the distance down to the topmost thingamabob. He didn't fall.

The red rock here is the Aztec Sandstone formation, Jurassic in age. Overlaying it in much of the canyon is a dark gray limestone, the much, much older Bonanza King limestone, from the Cambrian era. The older limestone got shoved up on top of the younger sandstone late in the era of the dinosaurs, when tectonic plates were compressing this part of the world, pushing up mountain ranges.

Late in the day, Pat is still working his way up.

landscape

Nevada

Hank

Las Vegas

rock climbing

Red Rock Canyon

cliff

ropes

Mar 6, 2012

In August 2004, during a family gathering on Peaks Island, Maine, to celebrate my father's eightieth birthday, some of the grandchildren spent many hours doing stuff with the rocks on the beach. Here we see Ted, Hank, Allen, Joe, and their cousin Nick.

In August 2004, during a family gathering on Peaks Island, Maine, to celebrate my father's eightieth birthday, some of the grandchildren spent many hours doing stuff with the rocks on the beach. Here we see Ted, Hank, Allen, Joe, and their cousin Nick.

If I remember correctly, shortly after this picture was taken, something catastrophic happened to the structure. The catastrophe was great fun for some of the boys, but not so much fun for Hank, who felt compelled to devote more hours to "fixing" it.

family

Peaks Island

Nick Horowitz

rocks

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

boys

Aug 3, 2012

Before last weekend's wedding, Bonnie the bride rehearsed with her attendants: her sister Caroline and longtime friend Katie. After the wedding, John the groom goofed around with his attendants: his brothers Ted, Joe, Allen, and Hank.

Before last weekend's wedding, Bonnie the bride rehearsed with her attendants: her sister Caroline and longtime friend Katie. After the wedding, John the groom goofed around with his attendants: his brothers Ted, Joe, Allen, and Hank.

wedding

John

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

Bonnie

Katie

Seattle

Caroline

(Before photo by Christine Salera; After photo by John Strelitz)

Aug 9, 2012

Hank interrupts his cleanup work to give us a thumbs-up from the back of the Raney Brothers BBQ truck in downtown Seattle.

Hank interrupts his cleanup work to give us a thumbs-up from the back of the Raney Brothers BBQ truck in downtown Seattle.

streetscape

Hank

work

Seattle

Raney Brothers BBQ

food truck

Nov 7, 2012

Hank Stein was recently sworn in as a senator in the University of Montana student government. Here, he and his roommate show off their matching shoes.

Hank Stein was recently sworn in as a senator in the University of Montana student government. Here, he and his roommate show off their matching shoes.

Hank

shoes

Pat

legs

duct tape

Dec 1, 2012

Heed this warning. It looks like a brick patio there on the campus of the University of Montana. Most people wouldn't be driving their cars there, off-road, amongst the campus walkways and picnic tables. But somebody might try to get in close to a building to make a delivery, say. We can hope they'll see this sign and stay off the brick patio.

Heed this warning. It looks like a brick patio there on the campus of the University of Montana. Most people wouldn't be driving their cars there, off-road, amongst the campus walkways and picnic tables. But somebody might try to get in close to a building to make a delivery, say. We can hope they'll see this sign and stay off the brick patio.

Because it is in fact a brick roof; deep underground below the patio are two big lecture halls. If the brick roof caved in under the weight of a vehicle, hundreds of students could be at risk.

Not only that, but one of our sons used to work as a janitor cleaning those underground lecture halls late at night. There's just no good time for driving onto the brick roofs of Missoula, Montana.

Hank

University of Montana

Missoula

signage

Jan 27, 2013

One variety of redwood tree, the dawn redwood, is deciduous, dropping its needles in the fall. This same variety happens to be the only kind of redwood that will grow in the eastern United States; this example of a dawn redwood appears to be thriving in the Fairmount Park arboretum in Philadelphia.

One variety of redwood tree, the dawn redwood, is deciduous, dropping its needles in the fall. This same variety happens to be the only kind of redwood that will grow in the eastern United States; this example of a dawn redwood appears to be thriving in the Fairmount Park arboretum in Philadelphia.

Dawn redwoods may be the midgets of the redwood family; coast redwoods and giant sequoias in California reach heights greater than 300 feet, while dawn redwoods, though very fast-growing, may not get much taller than 200 feet. Their potential height is not known for certain, however, because the oldest dawn redwoods in America are only about 70 years old now, descended from a single specimen found in China in 1944. In California, coastal redwoods and giant sequoias live for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Dawn redwoods were known to scientists from the fossil record long before the live specimen was found in China; they were assumed to be extinct. Fossilized dawn redwoods dating back to the Eocene, 50 or more million years ago, have been found in many parts of the world, including Greenland and islands in the Arctic Ocean, which had a tropical climate at the time. It is believed that the trees became deciduous in response to the extreme light-dark cycle of their high-latitude habitat; even though winters were not cold, they were very dark, rendering leaves or needles useless.

The young man in the tree, of course, is Hank, who is a college student studying ecology and climate change.

tree

Hank

Philadelphia

Fairmount Park

dawn redwood

tree climbing

Jul 11, 2013

summer

Hank

dawn

Vermont

Burlington

Rachel

Jacob

Sophie

Lake Champlain

Sarah

(Image credit: Hank Stein)

Aug 14, 2013

Last weekend, Hank, his climbing buddy Pat, and their other climbing buddy, the orange-footed yaller guy, summited Mount Gimli, a 9,000-foot spire of gneiss in the Valhalla Range of southeastern British Columbia.

Last weekend, Hank, his climbing buddy Pat, and their other climbing buddy, the orange-footed yaller guy, summited Mount Gimli, a 9,000-foot spire of gneiss in the Valhalla Range of southeastern British Columbia.

landscape

Canada

sunset

British Columbia

Hank

mountain

Pat

Mount Gimli

summit

Valhallas

(Image credit: Hank Stein)

Nov 4, 2013

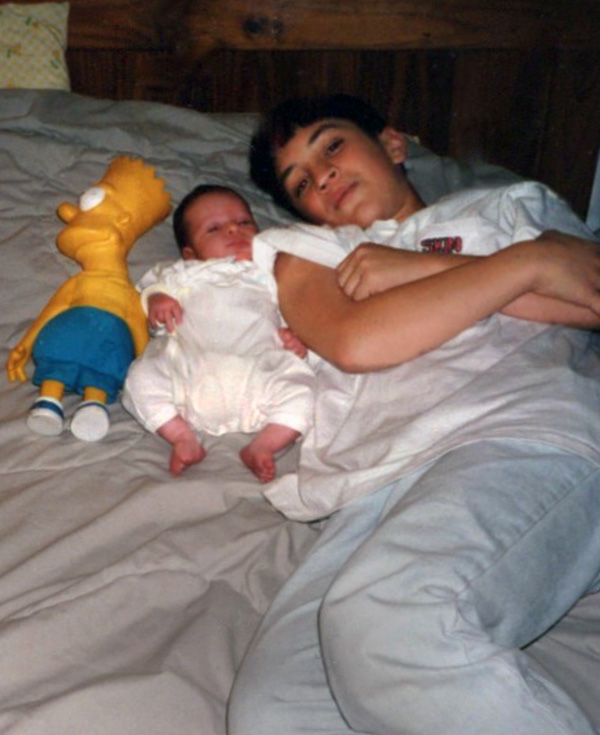

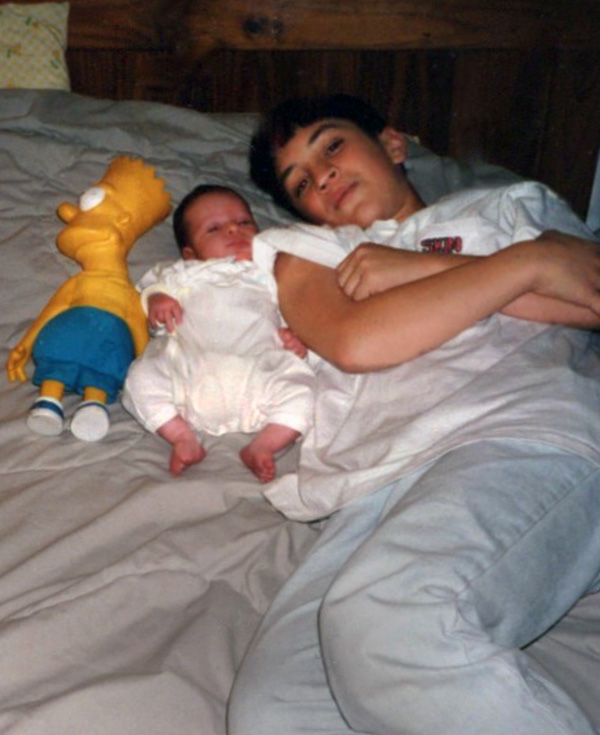

. . . that Bart Simpson doll? We have no idea. But the baby in the middle? He turns 21 today.

That would be our youngest baby, Hankystein, shown here with his biggest brother John. All grown up now, a serious, stand-up guy, already taking his hard turn at fixing the world. He says he'll celebrate his 21st tonight by watching a documentary about climate change. Maybe that's really what he'll do. The kids today.

Hank's a serious guy, and you can count on him, but he takes a way goofy tack when things are looking a little too sincere. For example, below, he's nearing the finish line of a 50-km trail run–that's 50 kilometers, as in more than 30 miles, up and over a mountain, a Rocky Mountain. He was running amongst the rocks for eight hours. And there near the end, he sees a photographer, and it appears that he digs deep and summons the energy to . . . well, to jump in the air and mug for the camera.

On this occasion, Hank, we offer advice from a couple of your great-grandmothers, who never quite got to know you but who still pull a lot of strings across generational and other divides. From your great-grandmother Harriet, after whom you are named, we share a warning not to run too much, lest you come down with toe cancer. And from your great-grandma Buddy, we share an all-purpose birthday wish: Wear it in good health.

John

Hank

Jan 25, 2014

Big brother is thirty-six and counting. He's got the young'un trained.

Big brother is thirty-six and counting. He's got the young'un trained.

brothers

John

Hank

Kater Street

JJ

Philly

Apr 11, 2014

This spring-break picture of Hank at the summit of the Stolen Chimney, a corkscrew spire atop the Ancient Art rockwall near Moab, Utah, has already been on Facebook, where it attracted a few comments. The award for Best Comment goes to Hank's Uncle Bob: "Get down from there this instant!"

This spring-break picture of Hank at the summit of the Stolen Chimney, a corkscrew spire atop the Ancient Art rockwall near Moab, Utah, has already been on Facebook, where it attracted a few comments. The award for Best Comment goes to Hank's Uncle Bob: "Get down from there this instant!"

mountains

tower

rock

Hank

Utah

climbing

Moab

pose

spire

Apr 12, 2014

Looks like yesterday's g'mornin was one silly mess: wrong boy, and even wrong uncle.

Looks like yesterday's g'mornin was one silly mess: wrong boy, and even wrong uncle.

This picture shows the real Hank Stein atop the twisted chimney at Ancient Art near Moab, Utah. Yesterday's picture was of some other somebody.

And the uncle who gave him a sort of shout out on Facebook–"Get down from there this instant!" That was his Uncle Rich. Yesterday's posting attributed those immortal words to some other uncle.

Apologies all around.

mountains

rocks

desert

Hank

Utah

Uncle Rich

climbing

Moab

Ancient Art

May 23, 2014

On Saturday, May 17, Hank got his diploma from the University of Montana College of Forestry. Shown here celebrating with him are his brothers Allen and John and his sister-in-law Bonnie.

On Saturday, May 17, Hank got his diploma from the University of Montana College of Forestry. Shown here celebrating with him are his brothers Allen and John and his sister-in-law Bonnie.

That very same day, Hank's cousin Andy Koehler also completed his college studies. Andy's degree, from Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York, is in music.

John

Hank

Bonnie

University of Montana

Missoula

Montana

graduation

Al

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Sep 10, 2014

Last month, Hank joined a group of Montanans climbing in the Andes, summiting above 18,000 feet in the middle of the Peruvian winter. They were closer to the Milky Way up there.

Last month, Hank joined a group of Montanans climbing in the Andes, summiting above 18,000 feet in the middle of the Peruvian winter. They were closer to the Milky Way up there.

landscape

mountains

night

rocks

Hank

stars

night sky

Andes

Huaraz

Milky Way

Peru

(Image credit: Ben Adkison)

Feb 10, 2016

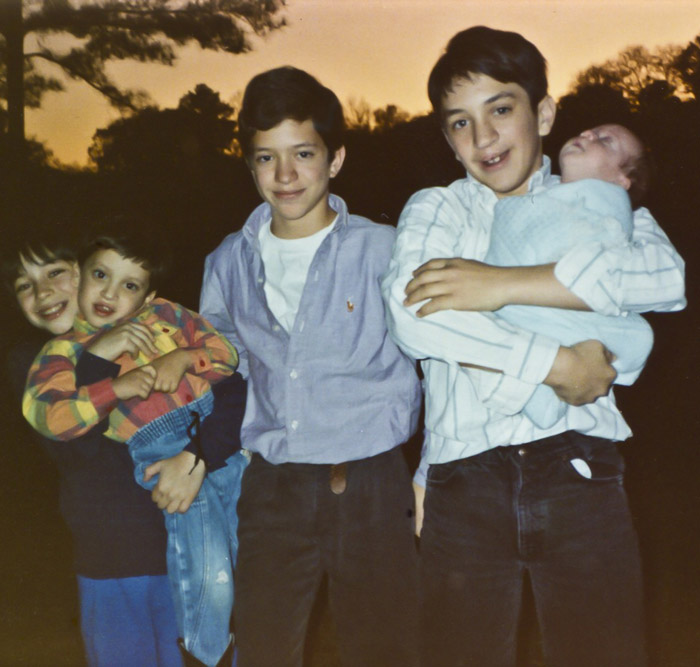

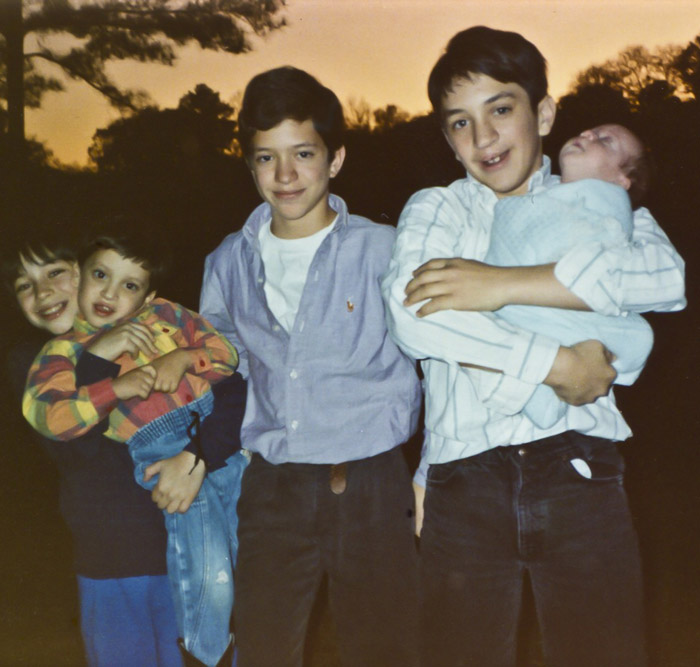

This is the earliest known photo of all five boys, taken at Forest Lake, Tuscaloosa, in November or December of 1992.

This is the earliest known photo of all five boys, taken at Forest Lake, Tuscaloosa, in November or December of 1992.

For what it's worth, all the trees in the background are gone now, shredded by the tornado in 2011. The boys, however, are still going strong: from left to right, there's Joe, now 34; Allen, 27; Ted, 36; John, who just turned 38; and bobble-headed newborn Hank, who's now 23.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

sunset

John

Joe

Ted

Allen

Hank

boys

Steins

Mar 4, 2016

In the winter of 2004, at the winter carnival in Québec City, eleven-year-old Hank met his doppelganger, the festival's mascot, Le Bonhomme. And Le Bonhomme met a little mascot of his own in smiling Hank.

In the winter of 2004, at the winter carnival in Québec City, eleven-year-old Hank met his doppelganger, the festival's mascot, Le Bonhomme. And Le Bonhomme met a little mascot of his own in smiling Hank.

winter

Hank

Quebec

snowman

carnival

2004

smiles

Feb 6, 2017

Blowing on a bird's belly–in this case, a common yellowthroat warbler–can reveal a lot of useful information.

Blowing on a bird's belly–in this case, a common yellowthroat warbler–can reveal a lot of useful information.

For example: Is she currently setting on a nestful of eggs? If so, then blowing back the feathers around her belly will reveal a patch of unfeathered skin. This is the brood patch; when mama bird settles down on the nest, her warm belly skin is in direct contact with the eggs, incubating them. Soon after they hatch, her brood patch will disappear.

And while you've got a bird in hand, you might as well spread out the wing feathers, as seen below on a spotted towhee, to learn the bird's age and get an idea of how many miles it's clocked:

More than two million times since 1989, through an ongoing program known as MAPS, scientists and volunteers at thousands of stations across Canada and the U.S. have captured wild birds, identified them by species, blown on their bellies and spread out their feathers and noted dozens of critical characteristics related to age and health, and then fixed tiny numbered bands around skinny little bird ankles and let them fly free.

The bird below is being fitted for its new ankle band:

Very early one morning last July, these birds and more than 50 others were trapped for banding at Morse Wildlife Preserve, near the headwaters of the north fork of Muck Creek, south of Tacoma, Washington. Three of the birds had been banded previously, and another three were banded that morning and then recaptured the same day.

Before dawn, the banding crew set up fine-mesh nets, known as mist nets, in a dozen clearings in the spruce forest and overgrown farmland at the preserve.

Banders checked the nets every fifteen minutes until about noon, and almost always, they found little birds snarled in the mesh. Very young birds may try to squirm their way out, but all the others hang immobile in the net, apparently in shock. We're told that the shock can be fatal, so banders try to un-net the birds gently but quickly; risk is greatest early in the morning, before the day has warmed up, when some birds may require warming under the banders' shirts. But such problems are exceedingly rare, and almost all the birds are released unharmed.

No one is allowed to touch these birds until completing comprehensive training in bird identification, handling, measurements, and other data-gathering, An early lesson involves the proper way to hold a captured bird, such as this common yellowthroat:

Over the years, bird banding for the MAPS program–Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship–has vastly improved our knowledge of bird migration patterns and has begun to focus on the links between bird populations and climate change. Banding teams return to each station every few days throughout the summer breeding season; the Morse preserve has participated in MAPS for almost twenty years.

Some MAPS banding is now high-tech, using miniaturized GPS transmitters that are now so small they can be attached to the legs of birds who weigh as little as 3 ounces, such as robins. Some MAPS stations now collect feathers for DNA sequencing. But the Morse program is old-school; the bands are tiny numbered strips of aluminum, and all the data associated with each band number–species, sex, age, body fat, condition of wing feathers, etc., etc., etc.–is entered by hand into logsheets on clipboards.

Although a bird in hand is a whole lot easier to identify than one on the wing or in a distant bush, the banding worktable was loaded with books and notebooks full of reference materials. For identification of birdsong, the banders had apps on their phones.

Not all species were bandable; hummingbirds, for example, were logged in and then released unbanded. We were told that teensy little hummingbird bands do exist, but handling them requires special certication. Two hummingbirds were caught that morning at Morse:

This freshly banded junco posed for a picture before flying off to get on with its life:

Hank

birds

Morse Wildlife Preserve

science

early morning

Tacoma, Washington

(Image credits: Fuji T)

Hank, in yellow, was the "customer" of a company that embroiders custom designs, such as team logos, onto anything you can think of--in this case, a Rumblebee! embroidered on a headband. The Rumblebees played ultimate frisbee last summer in a county league. Recently, Hank noticed that the embroidery company was offering discounts and other rewards in return for customer photos of the embroidered items in action. He sent them this photo, and they sent him fifty dollars and put his picture onto the front page of their website.

Hank, in yellow, was the "customer" of a company that embroiders custom designs, such as team logos, onto anything you can think of--in this case, a Rumblebee! embroidered on a headband. The Rumblebees played ultimate frisbee last summer in a county league. Recently, Hank noticed that the embroidery company was offering discounts and other rewards in return for customer photos of the embroidered items in action. He sent them this photo, and they sent him fifty dollars and put his picture onto the front page of their website. Hank swings his way up the wall in the climbing gym. Rock climbing has become a passion of his lately, but he says that climbing in a gym is not nearly as pleasant and exciting as climbing cliffs and boulders outdoors in the fresh air.

Hank swings his way up the wall in the climbing gym. Rock climbing has become a passion of his lately, but he says that climbing in a gym is not nearly as pleasant and exciting as climbing cliffs and boulders outdoors in the fresh air.

Stein boys doing their brotherly whatever on the street last summer in Seattle. From the bottom: brothers number 4, 1, and 5.

Stein boys doing their brotherly whatever on the street last summer in Seattle. From the bottom: brothers number 4, 1, and 5.

Hank interrupts his cleanup work to give us a thumbs-up from the back of the Raney Brothers BBQ truck in downtown Seattle.

Hank interrupts his cleanup work to give us a thumbs-up from the back of the Raney Brothers BBQ truck in downtown Seattle.

Heed this warning. It looks like a brick patio there on the campus of the University of Montana. Most people wouldn't be driving their cars there, off-road, amongst the campus walkways and picnic tables. But somebody might try to get in close to a building to make a delivery, say. We can hope they'll see this sign and stay off the brick patio.

Heed this warning. It looks like a brick patio there on the campus of the University of Montana. Most people wouldn't be driving their cars there, off-road, amongst the campus walkways and picnic tables. But somebody might try to get in close to a building to make a delivery, say. We can hope they'll see this sign and stay off the brick patio.

Looks like

Looks like