Nov 29, 2014

Stars fall on Alabama. In song, in meme, in license-tag slogan, in life and in legend. What follows is a long story about a good star and a bad star that fell on Alabama after lunch one day, out of a clear blue sky, sixty years ago this week.

Stars fall on Alabama. In song, in meme, in license-tag slogan, in life and in legend. What follows is a long story about a good star and a bad star that fell on Alabama after lunch one day, out of a clear blue sky, sixty years ago this week.

One of the stars would bring a little good fortune into the life of a poor farm family in the east-central part of the state. The other would bring fifteen minutes of fame and a whole lot of grief to a neighboring family, a husband and wife who were living, appropriately enough, across the road from the Comet Drive-In Theater.

The story of the good star was written up at the time in Ebony magazine. The story of the bad star was on TV and in all the newspapers, as well as Life magazine and National Geographic. That was the way it was.

Technically speaking, of course, the two stars were not stars at all; they were pieces of rock–meteorites–chips off of a meteoroid that had traveled millions of miles through the solar system before entering Alabama airspace. The meteoroid's orbital path had been much larger than, and at odds with, the earth's. Because it smashed into the sunlit side of earth near midday, it must have been headed away from the sun at the time. Astronomers calculate its likely origin as an asteroid they call 1685 Toro.

But that November afternoon, when the stars were falling on Alabama–when a bright white fireball and bone-jarring explosions were shattering the sky–nobody was thinking meteorites. They were thinking Soviet attack. Maybe an airplane was exploding, possibly because of flying saucers but more likely because of Russians. The U.S. Air Force base at Maxwell Field, near Montgomery, Alabama, was alerted to search for airplane wreckage and to protect Alabama from Soviet aggression.

The explosions and fireball had been generated when the meteoroid, traveling at about 30,000 miles per hour through empty space, suddenly impacted the top of the earth's atmosphere. The friction from air molecules vaporized most of the rock, blasted and charred the bits that remained, and slowed down the flight to a few hundred miles per hour.

It is estimated that for any significant fragments of a meteoroid to survive the flaming 40-second journey down through the atmosphere, the original size must be quite large, at least 150 pounds. The two known surviving chunks of this one weighed in at about 8 pounds and 3.5 pounds.

The smaller chunk fell onto a dirt road in the rural community of Oak Grove, five miles northwest of the town of Sylacauga. Late in the afternoon, it was spotted by a team of mules pulling a wagonload of firewood. The mules shied at the rock in the road, perhaps because it smelled of sulfur. Julius McKinney, the farmer who was driving the wagon, could not convince his mules to move on; figuring that they'd encountered a snake, he grabbed a stick of the firewood and climbed down into the road.

But it was only a black rock. McKinney tossed it off into the weeds at the side of the road and went on home.

By the next day, the other star that had fallen on Alabama from that meteoroid was the talk of the town. The other black rock had landed a couple of miles away from the one found by McKinney's mules; almost immediately, it had been confiscated by the police, who had locked it up for safekeeping and then turned it over to the air force.

But first, the police had brought it to a nearby gravel pit, where a state geologist, George Swindel, happened to be working that day on a groundwater survey; Swindel suspected it was just a piece of the local limestone, but after consulting his reference books he tested a chipped surface with a drop of acid. The rock didn't bubble the way limestone would, but it did emit a rotten-egg odor, the way a meteorite might. Swindel also noted a charred "crust" and numerous "thumbprint" indentations in the surface, two characteristic features of rocks that have made a fiery, turbulent plunge through the atmosphere.

Swindel's identification of the object as a meteorite changed the thrust of public conversation–forget about the Cold War; the space age had arrived in Sylacauga. Even though there was no such thing yet as an official, government-sponsored space age, people around town knew that this rock from outer space had put them on the map.

And the scent of money was in the air. There is a worldwide market for meteorites, with collectors and traders and speculators and scientific organizations all competing for the same few pieces of rock. Prices were rumored to be . . . astronomical, of course.

Based on all the gossip about the meteorite that Swindel had tested, Julius McKinney suspected that his mules had located a piece of the same stuff. He went back to the spot, found it in the underbrush, and carried it home.

But now what? McKinney wasn't sure what, if anything, his meteorite was worth, but he was sure of one thing: he'd never see a dime from it unless he found a white man to represent him, to make inquiries and pursue negotiations.

The only white man he trusted was the postman. McKinney turned the rock over to him.

Meanwhile, the other chunk of meteorite had the town in an uproar, and for good reason. Instead of showing up quietly on a lonesome country road, this other one had arrived in Alabama with a spectacular flourish.

It had hit the roof of a 140-year-old frame house along the Birmingham highway about three miles northwest of Sylacauga. God had willed it to go there, some said, because of the Comet Drive-In Theater across the street.

The meteorite had penetrated the asphalt shingles and wooden roof decking atop the house, grazed a rafter and joist in the attic, and burst through the three-quarter-inch tongue-in-groove wooden ceiling.

In the living room, it had smacked down onto a large Philco radio console, fracturing the laminated wood of the cabinet. The radio deflected the rock's trajectory, ricocheting it across the room, to the sofa where Ann Hodges lay wrapped in two quilts, trying to take a nap.

The rock hit her hard, severely bruising her left wrist and hip. And with that blow, Hodges became the only human being in modern times to take a direct hit from outer space.

There have been vague tales of similar occurrences in ancient and medieval days, but the names of no other victims have come down to us. And even today, sixty years later, Hodges's story is still a singular one; last year, people in Siberia were injured by flying glass from a meteorite-induced sonic boom, but no one other than Ann Hodges is known to have been actually touched by a falling star.

Hodges's mother, who was sewing in the next room, called the police. The women assumed something in the house must have exploded. Maybe the heater? Could the black thing be part of some machine? The first officer on the scene, Sylacauga's police chief W.D. Ashcraft, had been an eyewitness that afternoon to the pyrotechnics in the upper atmosphere–"like a gigantic welding arc," he said–and he had his own theories about the rock. It must be part of an airplane, he figured, or else part of a bomb that had made an airplane explode. It looked pretty plain and simple for any of that, however. He wondered if airplanes carried rocks for ballast, the way ships do?

Chief Ashcraft called for backup from the air force, which sent a helicopter carrying a couple of officers from Maxwell Field. The copter landed on the lawn in front of the high school, where the chief met the officers and showed them the rock. They were able to dismiss it immediately as unrelated to any aircraft, and they were also able to report that no planes were unaccounted for that day.

A helicopter at the high school, plus a mysterious black rock, plus a hole in the house across from the Comet Drive-In, plus whatever it was that had happened to Ann Hodges–this was one welding arc in the sky that had left Sylacauga in something of an uproar. Although Hodges's injuries were not severe, they were uncomfortable, and she was shaken and flustered and more than a little upset, both by what had happened to her and by the commotion. People were peeking in her windows and crowding her front door, straining to see the damage. Radio and newspaper reporters were hounding her for interviews. She was said to be a shy woman and prone to nervousness. The police said she begged them to make everybody go away, and so they whisked her off to the hospital, as much for privacy as for medical attention.

That evening, when her husband Eugene came home from work–he was a crew boss for a utility contractor, setting poles and clearing brush from the right-of-way–he found such a crowd on his front porch that he had to shove people aside to open the door. Inside, he found the hole in the ceiling, but both the rock and his wife had disappeared. Ann Hodges was hospitalized for five days, which was plenty long enough for the doctor to pose for a newspaper photographer while rearranging Hodges' clothing to reveal the nasty-looking bruise on her thigh. She averted her eyes awkwardly.

Meanwhile, the air force had whisked the rock off to its lab in Ohio "for further study." And the Hodgeses, who had quickly been made aware of the meteorite's potential monetary value, wanted it back. "I feel like the meteorite is mine," Ann Hodges told reporters. "I think God intended it for me. After all, it hit me."

God's intentions aside, the meteorite wasn't clearly hers. The public thought it was, but the way the law triangulates these things, rocks and minerals that show up naturally on private property belong not to the finder but to the owner of the property. Ann and Eugene Hodges didn't own the house they were living in at the time; they rented it from a woman named Birdie Guy, who was recently widowed and apparently quite anxious about her finances.

Guy quickly came forward to make her claim in the media. The meteorite was hers, she said, and she needed it badly; she was strapped for cash and would have to sell it to raise money to fix the damaged house.

Guy and the Hodgeses argued back and forth in the newspapers and on TV, and then they all lawyered up and filed suit.

Julius McKinney's rock, in the meantime, sat quietly with the postman, who had conducted a little discreet research into the meteorite market and had made contact with a few potential customers and agents, including a lawyer in Indianapolis who would represent McKinney in commercial negotiations. But in the early days of the meteorite frenzy, while the furor raged over the Hodgeses' piece of the rock, McKinney and the postman kept their secret.

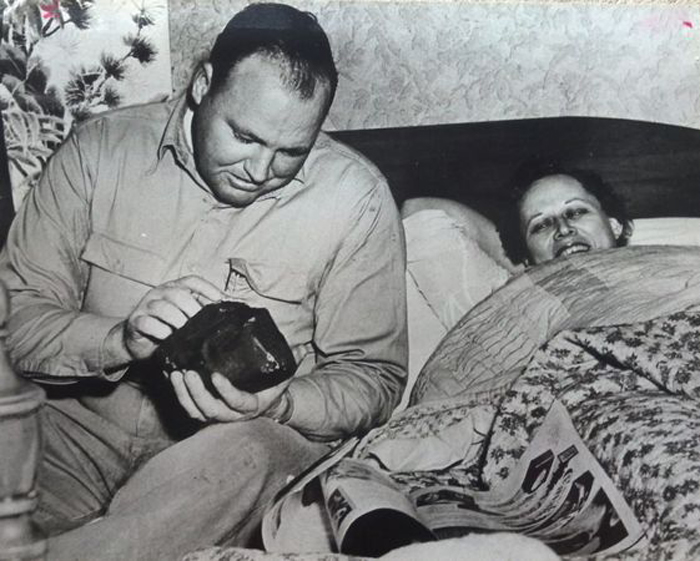

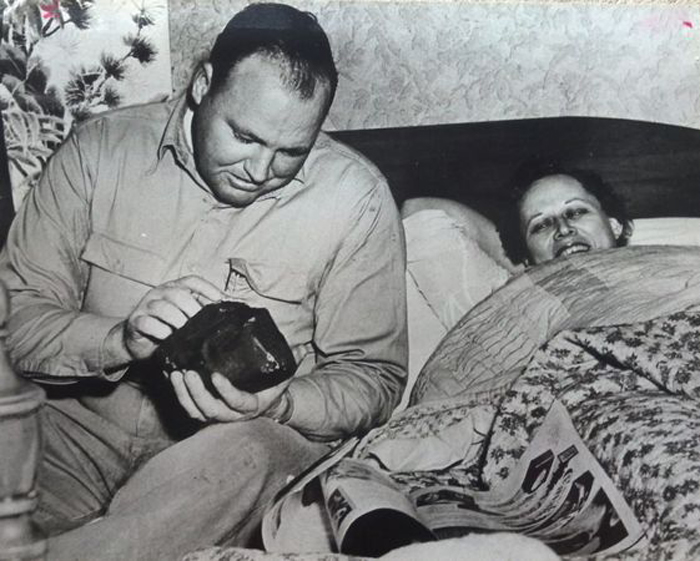

Ann Hodges was taken to New York to appear on national TV. Back at home, she and her husband posed in bed with the rock for photographers from Life magazine. They may have made a little money off their notoriety, but they had lawyers to pay. It took them two years to get the landlady's lawsuit off their backs, which they finally did by paying her $500 to drop her claim.

By then, all those eager meteorite-buyers that the Hodgeses had been dreaming about were nowhere to be found. The legal fuss had left some potential customers reluctant to get involved with such litigious sellers. And public attention had moved on; even in Sylacauga, people were no longer particularly interested in that rock. The Hodgeses couldn't find a soul willing to pay good money for it.

They'd gotten one offer, back in the beginning, from a representative of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. They had dismissed it then as ridiculously low. But now that title was finally clear and they could go ahead and sell the thing, they discovered that the Smithsonian was no longer interested.

Why? Because the museum had already purchased the McKinney chunk of the Sylacauga meteorite.

For how much? The price has never been made public, but it is reported that after the sale, McKinney and his family bought a house and a car and possibly also ten acres of farmland.

The Hodgeses finally gave their rock away. In 1956, they donated it to the Alabama Museum of Natural History in Tuscaloosa, where generations of schoolchildren have made it by far the most popular exhibit in the museum.

It is said that Ann Hodges never fully recovered from all that fell on her that day from out of the clear blue sky: not just her injuries, but the unwelcome attention, the media manipulation, and the stress and expense of the protracted legal battle, with its disappointing outcome.

Within a few years, she was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown. Her marriage ended. She became a recluse and an invalid. Sixteen years after being touched by a star, she died of kidney failure. She was 52 years old.

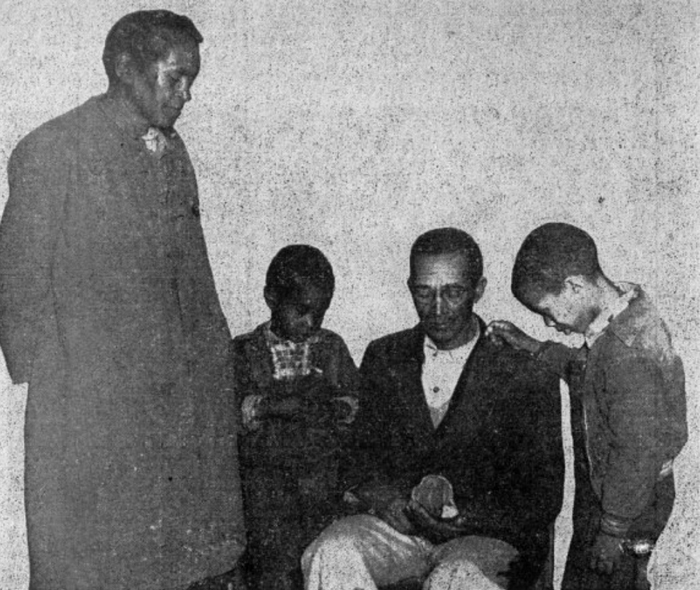

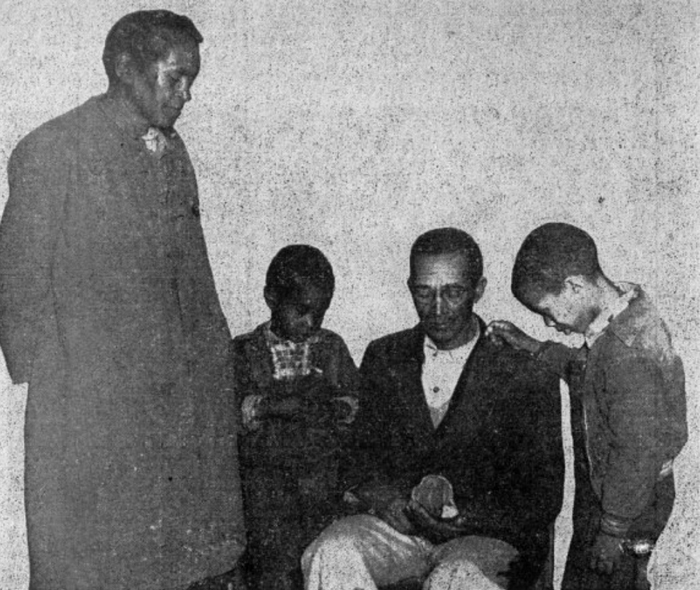

Julius Kempis McKinney was already older than that on the day he found his chunk of the meteorite; his date of birth is not recorded but is believed to be approximately 1897. He had joined the army in 1917 and fought in World War I. When he and his wife, Callie O'Neal McKinney, posed with the meteorite for a photographer from Ebony magazine, they included two of their grandsons in the picture.

A thin slice from his piece of the rock has been examined under a microscope by Smithsonian geologists, who were able to classify it as an H4 chondrite, one of the most common types of meteorites. It contains so much iron that it will deflect a compass needle by a degree or two. It also contains spherical crystals, which form only when mineral crystallization occurs in weightless outer space.

Meteorites are the oldest rocks ever found. Almost all of them are close to five billion years old, dating back to the early days of the solar system, when collisions between what we might call baby planets sometimes ejected chunks of planetary matter into wild and crazy orbits.

These rocks can fly through space for billions of years, it seems, but the minute they fall on Alabama, they make a ruckus.

Alabama

1954

Oak Grove

meteorite

Sylacauga