Hole in the Clouds

May 1, 2011

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

This is what one of the storms did to the house in Tuscaloosa where we raised our children. At least I think that's what we're looking at here; if it's not our old house, it's the house next door; there's not enough left to know for certain. The picture is disorienting in part because the house in the foreground near the waterfront, amongst the trees, must have been blown in by the storm from somewhere else; none of the houses on that side of Forest Lake was built so close to the water.

It's been forty years since an American city was shredded like this by an EF5 tornado, with winds exceeding 200 miles per hour; the last such storm was in 1970, when 26 people died in Lubbock, Texas. Wednesday's storm crossed through the middle of Tuscaloosa from southwest to northeast, devastating a path up to a mile and a half wide--about as wide as tornado paths ever get, according to the meteorological commentary I have been reading obsessively.

In some spots, winds were so strong that they ripped up the pavement and tore culverts out of the ground.

Our old neighborhood, Forest Lake, is pretty much in the geographic center of town. Most of it is gone now. The neighborhood just to the northeast, Cedar Crest, was hit even worse, if you can imagine that, and beyond Cedar Crest the neighborhood of Alberta City was completely obliterated, many houses reduced to clean slabs, with the debris sucked so high into the sky it returned to earth fifty or even a hundred miles away.

The house we lived in before this one was also destroyed, as was the elementary school all five of our boys attended.

We've been able to get in touch with almost all our old friends and neighbors, and they seem to be among the relatively lucky Tuscaloosans--homeless in some cases, but safe and sound. As of Saturday, the local death toll was 39 but expected to climb as rescue crews complete their search through the ruins.

More than 5,000 houses are damaged, and over 1,000 people have been treated for injuries at the hospital.

From now on, life in Tuscaloosa will be divided into a before and an after.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Forest Lake

tornado

home

May 12, 2011

The April 27 tornado that stayed on the ground for more than eighty miles through Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, has now been classified F4, not F5, as I mistakenly indicated in a posting here on May 1. There were three definite F5 tornadoes that same day, including one in north Alabama that completely obliterated the town of Hackleburg.

The April 27 tornado that stayed on the ground for more than eighty miles through Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, has now been classified F4, not F5, as I mistakenly indicated in a posting here on May 1. There were three definite F5 tornadoes that same day, including one in north Alabama that completely obliterated the town of Hackleburg.

But F4 is plenty bad enough. Forty-one people died in Tuscaloosa.

This is what's left of our old house. It was a two-story house, but the second story was set back a bit, and it's completely gone. At the extreme right of the picture is the doorframe for the front door, which is gone. At left is a spray-painted "Katrina cross" indicating that the rubble was searched on April 28 by search team "M," and no people or pets were found.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

house

ruins

tornado

(Image credit: Ben Shankman)

Jun 9, 2011

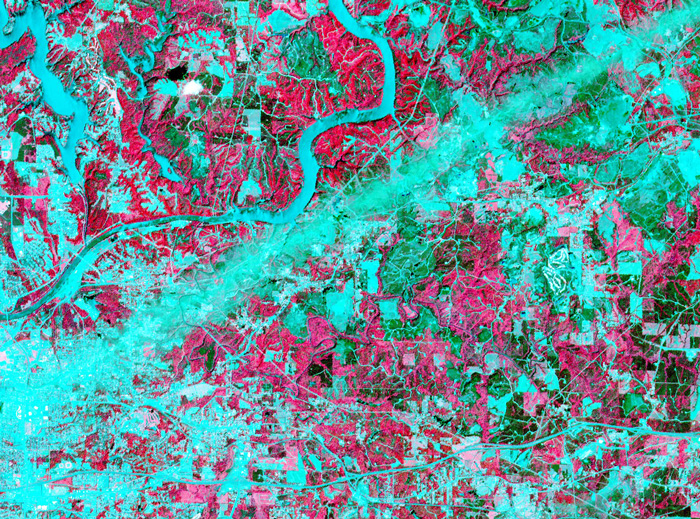

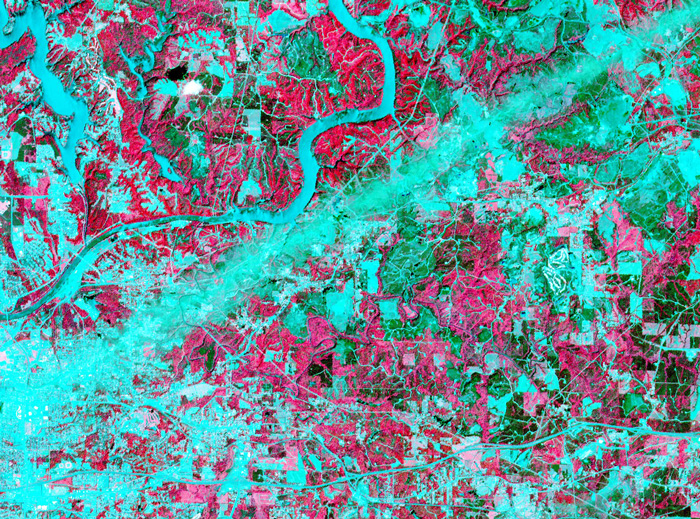

On April 28, 2011, the visible-light and infrared sensors of NASA's ASTER satellite captured this image of Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, which had been raked by an especially large and powerful tornado just the day before.

On April 28, 2011, the visible-light and infrared sensors of NASA's ASTER satellite captured this image of Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, which had been raked by an especially large and powerful tornado just the day before.

Infrared sensors are useful for distinguishing between vegetated and non-vegetated land cover. The pink areas in the photo represent vegetation–forests, pastures, cropland, golf courses. Areas that show up as aqua are non-vegetated or very lightly vegetated–cities, highways, rivers, strip mines, recent clearcuts.

The tornado track is obvious here: a straight aqua-colored streak running from the southwest to the northeast. Vegetation in this streak that was not directly destroyed by the storm was so littered with pieces of buildings and household objects that satellite sensors could barely detect it.

Just north of the storm track is the twisting course of the Black Warrior River, which shows up in aqua. The city of Tuscaloosa is mostly south of the river, at the left edge of the picture. In the upper left corner of the picture is Lake Tuscaloosa, a dammed-up tributary to the Black Warrior that provides the city's drinking water.

NASA's spokespeople assert that images such as this one can be useful in the aftermath of storms. They may help identify storm-damaged places outside of populated areas, where tornadoes might escape public awareness. And by proving the time and location of tornado paths, they could help homeowners support their insurance claims for storm damages.

If you click on the picture to see the larger version, you can follow numerous roads out into the countryside and observe that many of them seem to end with a little dot of aqua, indicating a non-vegetated spot. These are well pads for methane rigs. About fifteen years ago, the Black Warrior basin was the scene of one of the nation's first methane gas drilling booms. Coalfields underlie much of west Alabama, including almost all of Tuscaloosa County, but until recently the methane gas associated with coal deposits was considered a danger rather than an economically valuable fuel. "Fracking" technology, in which high-pressure liquids are injected deep into the earth to crack open the rocks hosting methane, was developed and refined in Alabama; drilling for methane is now under way all over the world. Unlike oil or traditional natural gas, methane is best extracted by small wells located within a few hundred feet of numerous other small wells; thus, the countryside is speckled with hundreds or thousands of separate well pads.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

birdseye view

infrared

satellite imagery

tornado

methane

fracking

(Image credit: NASA ASTER satellite)

(h/t: Chuck Horowitz

Mar 23, 2012

Last week, the Forest Lake homeowners' association in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, began siphoning the water out of Forest Lake, in hopes of revealing the debris that has collected in the lake since Tuscaloosa was devastated by a monster tornado eleven months ago.

Last week, the Forest Lake homeowners' association in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, began siphoning the water out of Forest Lake, in hopes of revealing the debris that has collected in the lake since Tuscaloosa was devastated by a monster tornado eleven months ago.

The lake sits in the geographic center of Tuscaloosa and was near the center of the tornado track. Virtually all the surrounding houses were destroyed, along with the trees that gave the neighborhood its name.

Yesterday, when the water had dropped to the level seen in this photo, engineers were able to make preliminary estimates of the cost of debris removal: just under $300,000, about 30% less than anticipated. Even though the lake is privately owned by the homeowners' association, the taxpayers will be paying for cleanup; the city hopes to share the cost with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resrouces Conservation Service.

Tuscaloosa

Alabama

Forest Lake

tornado

storm

debris

(Image credit: Chris Pow, al.com)

Jun 3, 2014

This is the time of year when, in many places, the first springtime crop of mosquitoes takes to the air at once and . . . swarms.

This is the time of year when, in many places, the first springtime crop of mosquitoes takes to the air at once and . . . swarms.

The Alaskan tundra and other Arctic-like regions are notorious for huge dark clouds of skeeters, hovering hungrily and buzzing, whining--call it screaming for blood.

But this photo was taken last week in Portugal, in the salt marshes near Vila Franca de Xira. The swarm affected the shape of a tornado, and perhaps inspired a bit of the fear associated with tornadoes. But it wasn't really a cyclone; the flight pattern of the little bloodsuckers wasn't rotational, just the usual brownian motion within the overall swarm. And the top of the swarm was much closer to the viewer than the bottom, which is why it appears wider.

We are told that outside of the tropics, people don't really die from mosquito bites, even if they get hundreds of bites, as in a serious swarm. They don't die; they just wish they would.

sky

seascape

Portugal

insects

tornado

ocean

marshes

cyclone

mosquitoes

Vila Franca de Xira

(Image credit: Ana Filipa Scarpa)

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

On Wednesday, 27 April 2011, an outbreak of severe tornadoes unmatched in the U.S. since 1932 destroyed homes and neighborhoods across the Southeast from Mississippi to Virginia. Hundreds of people died.

This is the time of year when, in many places, the first springtime crop of mosquitoes takes to the air at once and . . . swarms.

This is the time of year when, in many places, the first springtime crop of mosquitoes takes to the air at once and . . . swarms.