Hole in the Clouds

Sep 15, 2009

It's springtime in New Zealand, time for the Stein sheep to get themselves sheared. Here, Moe is already nekkid, while Curly waits her turn. A., the family shepherdess, says she is "contemplating" learning to spin the wool.

animal

sheep

New Zealand

A.

(Image credit: A. at kiwi-stories)

Jan 28, 2010

A few months ago, the New Zealanders among us were out touring their island--New Zealand's North Island--when they stopped for the night at the Okopako Farm Lodge in Opononi, Northland, a backpackers' hostel at the end of a primitive gravel road--a road so narrow and winding and twisty, we're told, that it can't be driven after dark. The people who run the lodge, which is off the electrical grid, offer "fresh organic produce, homemade bread & farmhouse meals," and they also promise a nice view.

This is what dawn looks like from the deck of the lodge.

"I shot photo after photo," recalls A., "as the sun rose. Unfortunately, I was so engrossed in the scenery I left bread on a burner on one of those camp toasters until it thoroughly burned, and its blackened remains released a massive amount of smoke that set off the fire alarm. The fire alarm rang for about 20 minutes, which did not thrill the few other inhabitants of that place.

"The upside was that they were awakened in time to enjoy the sunrise, too."

landscape

New Zealand

mountains

birdseye view

Opononi

Northland

dawn

(Image credit: A

at happy to be here)

Nov 23, 2010

Uncle R in New Zealand recently attended a casting call for hobbits and giants. Those who know R are pretty certain there's a part in that movie with his name all over it.

Among the questions he was asked: Are you strong enough to run up and down a hill four times carrying a sword?

They say they'll let him know in about a month.

New Zealand

hobbit

giant

Feb 10, 2012

Not every mountain range could live up to the name The Remarkables, but these peaks on the South Island of New Zealand do a handsome job of it.

Not every mountain range could live up to the name The Remarkables, but these peaks on the South Island of New Zealand do a handsome job of it.

landscape

New Zealand

mountains

(Image credit: Trey Ratliffe)

Sep 17, 2012

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Our newest sheep, Little Fluffy Raincloud, at left in photo, was a gift from a friend of ours. We had three previously, Curly, Lari, and Mow, but Lari died recently of old age and is buried on our property, where she lived a full and happy life. Once your sheep have names, you cannot eat them. We need three sheep to keep the grass in our two paddocks.

The photo below is of our dog, Sesame, who immigrated to New Zealand with us (she is almost 12 now), and Trapper, our New Zealand cat. Both animals regularly follow A. and me when I walk to work in the morning.

Dec 1, 2013

We're on the road again, headed for faraway places–not Ragusa Ibla, the magical Sicilian place shown here, but the other end of the world, where it's summertime now and we get to dance at the wedding of another niece, Gillian, who is marrying Mark Openshaw next weekend near Wellington, New Zealand.

We're on the road again, headed for faraway places–not Ragusa Ibla, the magical Sicilian place shown here, but the other end of the world, where it's summertime now and we get to dance at the wedding of another niece, Gillian, who is marrying Mark Openshaw next weekend near Wellington, New Zealand.

Hole in the Clouds will remain update-free for a little while, till we make it back home around December 18–bearing stories and pictures, perhaps, but certainly carrying with us some of the energy and glow generated by this sort of happy family occasion.

As for Ragusa Ibla–some other day. Right now, we've got penguins and albatrosses to attend to, and sheep and glow worms and waterfalls and those absolutely outstanding kiwi accents.

Meanwhile, y'all can go ahead and start the holiday season without us. We'll catch up soon.

New Zealand

Sicily

Ragusa Ibla

wedding nieces

(Image credit: Katrin Maldre)

Dec 21, 2013

Out at Staglands wildlife park in the hills north of Wellington, New Zealand, amidst swans and doves and family and friends, our niece Gillian Stein married Mark Openshaw; husband and wife both changed their names to become Mr. and Mrs. Openstein.

Out at Staglands wildlife park in the hills north of Wellington, New Zealand, amidst swans and doves and family and friends, our niece Gillian Stein married Mark Openshaw; husband and wife both changed their names to become Mr. and Mrs. Openstein.

There was a hora in the Staglands barn, following a waterfront ceremony and plenty of Wellington-style ukelele music. Flying with the doves in the last photo below is best man Ben Hart.

New Zealand

wedding

nieces

Gillian Openstein

Mark Openstein

Ben Hart

Staglands

swan

doves

hora

(Image credits: Von Photography)

Dec 22, 2013

Among the happy occasions being celebrated recently while we were in New Zealand, in addition to the marriage of our niece, was the one hundredth anniversary of the invention of the zipper, as featured in the World of Wearable Art exhibition at Te Papa museum in Wellington.

Among the happy occasions being celebrated recently while we were in New Zealand, in addition to the marriage of our niece, was the one hundredth anniversary of the invention of the zipper, as featured in the World of Wearable Art exhibition at Te Papa museum in Wellington.

Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine, patented a zipper-like Automatic Continuous Clothing Closure in 1851 but was too busy selling sewing machines to get it to market.

Another zipper-like thingy, called a clasp locker by its inventor, Whitcomb Judson, was displayed at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. It was designed to close boots with long rows of hooks and eyes, and it attracted investors who built a company around the idea but couldn't ever make it work.

Then in the early twentieth century a Swedish-born electrical engineer named Gideon Sundback married the daughter of the company president and was named chief designer. He spent seven years refining a different zipper-like device that by 1913 actually worked. But the company was still stuck in boot-closure mode, and for the next twenty years B.F. Goodrich was the main customer for zippers, which were used on a style of rubber galoshes known as "Zips."

It wasn't till the 1930s that zippers were sewn into ready-made clothing: at first, in children's wear, then for fly closures in men's trousers, and eventually in coats, skirts, dresses, luggage, sports gear, and everything else.

museum

New Zealand

art

Elias Howe

Gideon Sundback

Whitcomb Judson

Wellington

clothing

Te Papa

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Dec 23, 2013

They eat guppies in New Zealand.

Actually, I don't know if they eat guppies there, but they definitely eat wormy little baby fish they call whitebait, which are similar to guppies in size, sliminess, and bug-eyedness.

Every spring, wherever rivers run into the sea in New Zealand, which is pretty much everywhere, people go whitebaiting. They rig up fine mesh nets from docks called whitebait stands or they pull up a chair along the riverbank or swing nets just inside the surfline at the river mouth. When the fish start running, the whitebaiters cook up their catch, usually as fritters made with egg and a bit of flour, often served on buttered bread.

The fish known as whitebait, which actually include at least five different species, are born in freshwater, get swept out to sea as babies, then return as juveniles to run upriver, where they will mature and spawn . . . if they don't get netted along the way.

Despite strict government regulation, the whitebait runs nowadays aren't what they used to be. A hundred years ago, whitebaiters caught more than they could ever hope to eat; they fed the excess to pigs or buried it in their gardens as fertilizer. In recent years, however, agricultural chemicals and population pressures in river valleys have destroyed much upriver whitebait habitat. Also, there's the obvious unsustainability of catching so many baby fish before they have a chance to grow up and reproduce.

Only in the nearly roadless region of South West New Zealand, where rivers plunge through rainforest from alpine heights to the coast, has whitebaiting remained as productive as ever. Whitebait buyers on the rivers there acquire the makings of fritters for stores and restaurants all over the country.

They're not cheap. In 2006, fresh whitebait went for $12.95 per hundred grams–about $60 a pound.

fish

New Zealand

coast

rivers

sustainability

whitebait

South West

(Image credits, from top: Juliette Armstrong, Rick Wilmore, Little Fuji)

Dec 24, 2013

We saw more rainbows in two weeks in the skies over New Zealand than we might expect to glimpse in two years in the States. Here's a sampling: above, in Queenstown on the South Island, and below, looking toward Wellington from Eastbourne on the North Island.

We saw more rainbows in two weeks in the skies over New Zealand than we might expect to glimpse in two years in the States. Here's a sampling: above, in Queenstown on the South Island, and below, looking toward Wellington from Eastbourne on the North Island.

New Zealand

sky

skyscape

Queenstown

Eastbourne

rainbows

(Image credits: Little Fuji, Little iPhone)

Dec 27, 2013

We open this post with a small step back in time, to October of this year, when our niece Melissa Koehler married Matt Solomon. We noted this elegant and awesome occasion at the time but somehow managed to omit any photo of the bridegroom. By now, photographers and videographers and Facebook contributors have documented the day in images worth a billion skillion words, and from all that treasure we selected a frame from a video, with its swirl of wind and an imminent kiss.

We open this post with a small step back in time, to October of this year, when our niece Melissa Koehler married Matt Solomon. We noted this elegant and awesome occasion at the time but somehow managed to omit any photo of the bridegroom. By now, photographers and videographers and Facebook contributors have documented the day in images worth a billion skillion words, and from all that treasure we selected a frame from a video, with its swirl of wind and an imminent kiss.

Below are pictures of four other of our nieces, two sets of sisters, taken as they celebrated with Melissa that day. At left are Maggie and Amelia; to the right are Avi and Gillian. These pictures are tightly cropped to feature the nieces; people have been cropped out literally and perhaps also figuratively as we try to keep the focus on these young women.

Gillian's wedding, of course, was just this month in New Zealand. Maggie's was back in June in Maine. Gillian works in Wellington, New Zealand, organizing ecotourism adventures. Maggie is a nurse in Rochester, New York, studying to become a nurse practitioner.

Maggie's little sister, Amelia, wearing blue in the picture, lives and works in New York City, where she is creative director for a brand new startup fashion label, The Girl That Loves. Amelia prepares marketing materials and designs the company's overall look and feel.

Who is The Girl That Loves? According to the website, she's a girl who's "going places, but she plans to have a good time getting there."

She mixes edgy and trendy pieces with cute and playful pieces. Her favorite combo? Sexy heels, jeans and a sweatshirt (and possibly a fedora). Tadaaaa! Looking great has never been so comfy! Instead of breaking her bank over one designer piece she lines her closet with a variety of fun pieces. She likes simple, elegant clothing but enjoys taking an occasional risk: the right neckline, a bit of cool embroidery or an edgy color scheme can turn a piece from “like” to “love.”

Here is one of The Girl That Loves' new designs, in the playful category, a rhinestone panda skirt that perhaps, when some people wear it, can go from "like" to "love" in a heartbeat.

At the other end of the world from New York City, on New Zealand's South Island, Amelia's cousin Avi is herself no slouch when it comes to fashion; in fact, she once was almost turned down for a job because an interviewer thought she dressed much too nicely for someone in her line of work. Avi earns her living by studying penguins in their natural habitats.

She's just beginning a new position at Oamaru Blue Penguin Colony, on the east coast of New Zealand about three hours' drive south of Christchurch. There at the edge of town, hundreds of little blue penguins, the world's smallest penguin species, sometimes called fairy penguins, have colonized an abandoned limestone quarry, making their nests at the top of a steep rocky slope just outside Oamaru's harbor.

Most days, the penguins leave the colony before dawn to swim several miles to their fishing grounds offshore; they fish all day and then return home at nightfall. Their nightly return has become something of a tourist attraction in Oamaru, so much so that an important research focus for scientists like Avi is how best to manage interaction between the public and the penguins.

Below is a huddle of Oamaru penguins just back from the sea; they swam in together as a "raft" and then paused amidst the rocks, perhaps just to catch their breaths and cool off after their long swim. Penguins' greasy feathers keep them very warm, so warm that to prevent overheating they have to fluff themselves, as they've done here, to allow chilly evening air to reach their skin.

Little blue penguins are not endangered, but many local populations are at risk because of land predators such as dogs and cats, which are not native to New Zealand. In the water, they are preyed upon by fur seals. In some coastal areas, they get hit by cars while trying to cross the road at dusk.

At the bottom of this post is a portrait of a little blue guy. He weighs about four pounds or less and is only 12 inches tall, not even knee high to a ten year old.

New York

New Zealand

fashion

Melissa

Amelia

Maggie

Avi

Gillian

penguins

Oamaru

The Girl That Loves

Dec 28, 2013

New Zealand

anniversary

boat

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jan 2, 2014

New Zealand is a kingdom of birds. Evolution provided the land with no big predators–in fact, no mammals at all except for a few tiny bats. Birds ruled. They didn't even need to fly to live safely and well in New Zealand; flightless birds–penguins, kiwis, and nine species of giant moa, among many others–found food and nesting sites right on the ground all over the place.

New Zealand is a kingdom of birds. Evolution provided the land with no big predators–in fact, no mammals at all except for a few tiny bats. Birds ruled. They didn't even need to fly to live safely and well in New Zealand; flightless birds–penguins, kiwis, and nine species of giant moa, among many others–found food and nesting sites right on the ground all over the place.

Humans arrived with guns and quickly shot all the moas. Also, people began harassing the other birds with imported varmints that ate eggs and/or birdmeat. We are a pretty pathetic excuse for a species.

But some of the birdlife seems to have evolved to seek a certain revenge. Case in point is the kea, the world's only alpine parrot, endemic to New Zealand's high country. Wherever roads lead to mountain passes or overlooks, keas are hanging out in the parking lots, waiting for cars to chew.

Keas gnaw on and can completely destroy the rubber fittings on automobiles, such as gaskets around windows and antennas. They also eat ice cream a scoop at a time off a handheld cone, and they can figure out how to open backpacks and devour all the food inside.

New Zealand

bird

Te Anau

Milford

kea

parrot

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jan 8, 2014

The little guy here in the white apron, with a pencil behind his ear–that's Mr. 4, the grocer-mascot of New Zealand's ubiquitous Four Square chain of supermarkets.

The little guy here in the white apron, with a pencil behind his ear–that's Mr. 4, the grocer-mascot of New Zealand's ubiquitous Four Square chain of supermarkets.

The mural featuring Mr. 4 covers a side wall of the art museum in Christchurch. The museum is closed at the moment and has been for a couple of years. All the artwork currently on exhibit is out in the streets of the city, like this piece.

Perhaps you are wondering why in the picture below there's a crane on top of the museum? Hold that thought; we'll get to it soon.

museum

New Zealand

art

streetscape

earthquake

mural

crane

grocery store

logo

Christchurch

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jan 11, 2014

On 22 February 2012, white-painted chairs were set up alongside busy Cashel Street in Christchurch, New Zealand, each one different from the others, all of them empty. They covered a freshly sodded swath of a freshly vacant lot, where Baptists used to go to church before an 18-second-long earthquake took out the church, along with about 8,000 other buildings in town.

On 22 February 2012, white-painted chairs were set up alongside busy Cashel Street in Christchurch, New Zealand, each one different from the others, all of them empty. They covered a freshly sodded swath of a freshly vacant lot, where Baptists used to go to church before an 18-second-long earthquake took out the church, along with about 8,000 other buildings in town.

The chairs memorialize the 185 residents of Christchurch who died in the quake. One hundred fifteen of them were in a six-story office building that day across the street from what is now the memorial; in 18 seconds, the building pancaked and caught fire.

The chairs appeared one year to the day after the quake. Like so much else in the city's recovery from the disaster, the chair memorial, designed by Peter Majendie, was planned as transitional and very temporary, to remain on display for a week.

It's still there. Believe it or not, vandals steal chairs from the memorial every now and then, but so far at least, they've been replaced.

This transition stuff can be tough. New Zealand's latest census figures came out last month, revealing that more than 40,000 people have left Christchurch since the earthquake. The city is no longer the country's second largest. The official estimate now is that recovery will take twenty years, minimum.

Here is how people in Christchurch described the quake to us: the earth heaved straight upward, we were told, and then plummeted, slamming back down. Eyewitnesses reported seeing people literally thrown up into the air.

The next several posts will look at what's going on there nowadays, a little less than three years later.

New Zealand

streetscape

earthquake

chairs

memorial

Christchurch

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jan 13, 2014

Before the earthquake, Christchurch had two cathedrals: the Gothic-style Anglican Christ Church Cathedral on the city's central square and the Italianate Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament nearby. Both were ruined in the quake.

Before the earthquake, Christchurch had two cathedrals: the Gothic-style Anglican Christ Church Cathedral on the city's central square and the Italianate Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament nearby. Both were ruined in the quake.

In the aftermath of the quake, both the Anglican and the Catholic establishments became notably secretive about their plans for rebuilding and/or repair. The Anglicans were sued over insurance payouts and municipal maintenance funds. The Catholics spirited away all the decorative elements and artwork from their cathedral and hid everything at a still-undisclosed location.

Both cathedrals sit in ruins today, not yet demolished, propped up by flying buttresses made of steel I-beams and stacks of shipping containers filled with concrete.

Meanwhile, the Anglicans have built a new cathedral, allegedly for temporary use, on the site of a nearby church that was also destroyed in the earthquake. The new cathedral, with its cardboard-tube roof beams, was designed pro bono by Japanese architect Shigeru Ban, who has achieved worldwide acclaim for his post-disaster structures, many of which are built from inexpensive and readily available materials, including paper, cardboard, plastic crates, and shipping containers.

The new Cardboard Cathedral opened last August. It can hold 700 people for church services and also serves as public meeting space.

New Zealand

architecture

earthquake

church

Christchurch

Shigeru Ban

Jan 14, 2014

New Zealand

cityscape

streetscape

earthquake

ruins

Christchurch

Jan 16, 2014

Public restroom on Queen's Wharf in Wellington, New Zealand.

Public restroom on Queen's Wharf in Wellington, New Zealand.

New Zealand

cityscape

streetscape

infrastructure

Wellington

restroom

wharf

dock

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jan 24, 2014

Our niece Avi, in shades, and her friend Tahu put their heads together in the noonday sun at the farmers' market in Dunedin, New Zealand. Tahu had a singing gig at the market that day, with her band Tahu and the Takahes.

Our niece Avi, in shades, and her friend Tahu put their heads together in the noonday sun at the farmers' market in Dunedin, New Zealand. Tahu had a singing gig at the market that day, with her band Tahu and the Takahes.

New Zealand

Avi

Dunedin

Tahu

farmers' market

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Feb 7, 2014

In Sochi, we're told, the Russian government spies on you while you're in the shower. Well, in Queenstown, New Zealand, corporations try to sell you stuff while you're in the shower; the walls of the shower stall at our "holiday park" were papered over with ads for, in this case, winery tours.

In Sochi, we're told, the Russian government spies on you while you're in the shower. Well, in Queenstown, New Zealand, corporations try to sell you stuff while you're in the shower; the walls of the shower stall at our "holiday park" were papered over with ads for, in this case, winery tours.

New Zealand

marketing

bathroom

Queenstown

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Feb 10, 2014

Apparently, these tourists in Queenstown, New Zealand, have no intention of sharing their Fergburgers with attentive local ducks.

Apparently, these tourists in Queenstown, New Zealand, have no intention of sharing their Fergburgers with attentive local ducks.

food

New Zealand

ducks

park

Queenstown

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Feb 21, 2014

When we returned from New Zealand late last year, we were particularly eager to share pictures of the really interesting, stretch-of-the-imagination stuff we'd encountered there: car-eating parrots, cardboard cathedrals, a parkour professor, and of course an awesome ukelele wedding.

When we returned from New Zealand late last year, we were particularly eager to share pictures of the really interesting, stretch-of-the-imagination stuff we'd encountered there: car-eating parrots, cardboard cathedrals, a parkour professor, and of course an awesome ukelele wedding.

We'd set out for New Zealand hoping for this sort of serendipity but knowing for sure we'd see scenery: mountains, waterfalls, forests of hobbity vegetation, cities with flowers, beaches and cliffs, and, of course of course, sheep. We lucked out with all of that as well.

And needless to say, we got pictures.

So for the next little while, we'll share some shots of the real New Zealand, beginning tomorrow with The Silver Fern

New Zealand

mountains

clouds

Milford Sound

waterfalls

scenery

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Feb 22, 2014

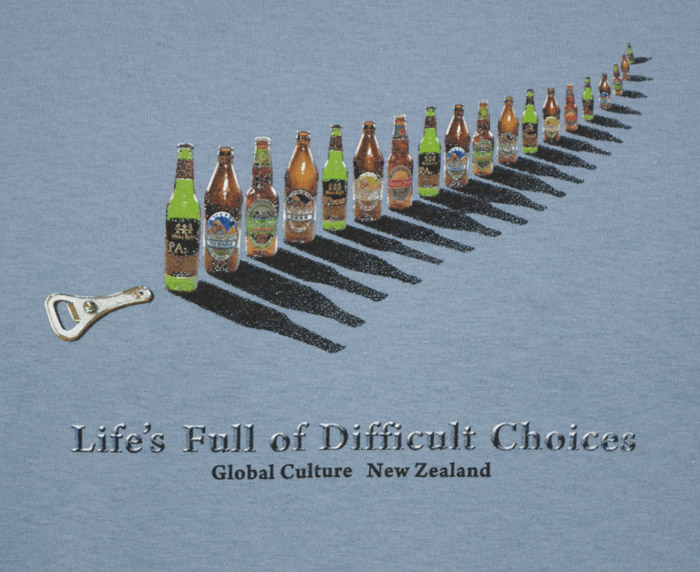

New Zealand is a land of ferns, notably of tree ferns, which give many Kiwi forests a certain Jurassic Park sort of character. And of course it is also the land of the silver fern, which is botanically one of the endemic tree ferns and artistically an abstracted swirl of a fern frond, as much corporate-style logo as patriotic emblem.

How many countries have logos? One recent Kiwi prime minister thought the silver fern belonged on New Zealand's flag, which Kiwis don't seem to wave or display very much and which foreigners often confuse with Australia's flag.

There's no silver fern on the flag–yet–though it's been on numerous coins and stamps over the years. The world knows it as the symbol of the fearsome All Blacks rugby team, and it is also associated with centuries-old Maori cultural motifs.

Recently, the silver fern has shown up on airplane fuselages, t-shirts, tattoos, beer commercials, wedding cakes, and the foaming milk atop expresso drinks.

New Zealand

logo

ferns

motif

All Blacks

forest

silver fern

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Feb 24, 2014

Point your camera at pretty scenes in New Zealand, and it won't take long before you notice how many of your snapshots include a fringe or scrim of tall red-brown lilies.

Point your camera at pretty scenes in New Zealand, and it won't take long before you notice how many of your snapshots include a fringe or scrim of tall red-brown lilies.

They call the lilies flax, which makes no sense. In the northern hemisphere, flax is the name of a field crop, a bushy, weedy looking plant grown for linen fiber and linseed oil. In New Zealand, flax is the name for a group of native lilies that grow wild all over the countryside, around mountain lakes and seaside marshes, in suburban yards and rural hedgerows and the far-flung edges of uninhabited woodlands.

New Zealand flax got its name as a marketing gimmick. The Maori called these lilies harakeke, and they used their fibrous leaves for weaving baskets, fishing nets, ropes, cords, mats, and all sorts of clothing, from rough raincloaks to fine gowns decorated with feathers. By the mid-nineteenth century, the strength and durability of the fiber was known around the world, particularly for ropes, fishnets, and cordage; the Maori began cultivating the lilies in huge plantations, sometimes using slave labor to tend the lilies and strip the leaves for fiber to sell to Europeans. The Europeans, smelling money, promoted New Zealand "flax" as a high-quality version of that Old World lineny stuff.

Meanwhile, Maori continued to weave their flax into goods for their own use, including baskets, as depicted below in a 1903 painting by the Czech artist Gottfried Bohumir Lindauer; the flax baskets in the painting are being woven by women who are wearing garments also woven from New Zealand flax fiber. Lindauer, trained as an artist in Vienna, fled to New Zealand to avoid military service in the Austrian army and discovered he could make a living painting scenes of Maori life.

Below the painting here are additional views of New Zealand flax in bloom.

New Zealand

flowers

plants

1903

Gottfried Bohumir Lindauer

flax

lilies

Maori

(Photos by Little Fuji)

(Painting by Gottfried Lindauer)

Mar 5, 2014

Lupin–from North America–and gorse–from Europe–are valued plants in much of the northern hemisphere. They were intentionally imported into New Zealand, lupin as a showy garden flower, gorse as a golden-blooming hedgerow plant to help farmers establish the boundaries of their pastures.

Lupin–from North America–and gorse–from Europe–are valued plants in much of the northern hemisphere. They were intentionally imported into New Zealand, lupin as a showy garden flower, gorse as a golden-blooming hedgerow plant to help farmers establish the boundaries of their pastures.

Both plants grew well in New Zealand and quickly became naturalized, spreading across much of the countryside, crowding out native bush, reducing habitat for native animals, and eventually finding themselves on the official registry of invasive species and noxious weeds.

Gorse is much the worse offender, now occupying 5 percent of New Zealand's land area and virtually impossible to eradicate. In Europe, gorse thickets are functional living fences around fields and pastures. The hedgerows break up areas of agricultural monoculture, providing habitat for wild birds and other native critters, and the thorny branches help farmers keep "wild" animals out of the fields and grazing animals in place. In New Zealand, however, gorse jumps right out of any hedgerows, displaces both native plants and cultivated crops, and swallows up all the open land thereabouts, till there's no grass left for the sheep and cattle. In just a few years, a gorse infestation can reduce pastureland and cropland to worthless, thorny scrub that is highly prone to catching fire.

Gorse seeds survive for many years in the soil near their parent plants. If the plants are pulled out or killed, the seeds immediately germinate in the disturbed soil and quickly, vigorously, happily replace whatever gorse has been laboriously removed.

Lupin too, is happy in its adopted New Zealand home (even though Kiwis drop the "e" that Americans just know belongs at the end of the plant's name). The lupin species that has made itself at home in so much of the country is Russell lupin, native to western North America and noted for the range of color on its spectacular flower spikes. Russell lupin likes conditions in New Zealand so well it has learned to thrive there even in places without soil, such as in the wide open gravel beds of the South Island's famed braided rivers.

Braided rivers are actually a rare kind of habitat, found in Alaska, western Canada, New Zealand's South Island, and very few other places. They flow steeply down from rapidly eroding mountains, carrying lots of sediment but not much water except during spring snowmelt, when the gravel is scoured clean. During times of low water, shallow streams and pools meander through the gravel, habitat for rare birds and fish. But when lupin colonize a braided river, the dense mats of their roots and stems trap sediment, choking off the riverwater, pinching its flow into relatively deep, narrow, fast-flowing channels that native fish and birds can't survive in.

Lupin spreads across a braided riverbed at the rate of about two meters a year. And the riverwater washes the lupin seeds downstream, to begin new colonies.

The photo at the top of this posting shows both lupin and gorse becoming established at the edge of a braided river near Arthur Pass.

Photo 1 below: Gorse has conquered the hillside at left in the Taieri Gorge west of Dunedin and is spreading to still-pastoral hillsides in the photo's background.

Photo 2: A sheep picks its way between thorny gorse bushes in a pasture with little grass left to eat.

Photo 3: Beautiful lupin grows dreamily in the highlands around Lake Tekapo.

Possible error message: We are decidedly non-expert in the art and science of plant identification. What we claim is gorse in the photos here may actually be one or more of several vaguely gorse-like species, perhaps Scotch broom, which is also an invasive noxious weed, or perhaps a native Kiwi type of broom, which is not considered weedy at all because it keeps to its place in the ecological scheme of things.

sheep

New Zealand

flowers

plants

invasive species

braided river

Mar 7, 2014

East of New Zealand's highest mountain ranges are the tussocklands: relatively dry and wide open hills and plains somewhat reminiscent of western North America's sagebrush country. The clumps of vegetation, however, are not sage but tussocky grasses, and the overall landscape, sweeping and dramatic as it appears, is not natural to New Zealand.

East of New Zealand's highest mountain ranges are the tussocklands: relatively dry and wide open hills and plains somewhat reminiscent of western North America's sagebrush country. The clumps of vegetation, however, are not sage but tussocky grasses, and the overall landscape, sweeping and dramatic as it appears, is not natural to New Zealand.

People, originally Polynesians and eventually Europeans, created tussocklands by burning off the original vegetation, which included dryland trees and scrub. In recent times, European immigrants created an environment in which tussocklands became more or less permanent features of the New Zealand landscape; this was accomplished by driving to extinction several species of animals, notably giant moa, that would otherwise keep tussock grasses under control and facilitate regrowth of the original forest.

Tussock grasses don't make good forage for domesticated animals, but they do help shelter tastier, tender imported grasses and legumes that might be planted there for sheep and cows. Thus, well-tended tussockland can become decent rangeland for livestock. And particularly well-tended tussockland, especially in warmer, lowland regions of New Zealand, can be developed into premium pastureland of the sort that generated a worldwide reputation for New Zealand wool and, recently, dairy products.

New Zealand

Otago

grasses

tussockland

Queensland

(Image credits: Little Fuji)

Mar 11, 2014

Back in March 1866, Greymouth was a rough little gold rush town on New Zealand's wild west coast, crowded with young men scheming to get rich quick, many of them immigrants from Ireland. While most of the town celebrated St. Patrick's Day that year, a man named Synder Browne huddled in a tent near the muddy outskirts of town, setting type by hand for the first edition of Greymouth's second newspaper, the Evening Star.

Back in March 1866, Greymouth was a rough little gold rush town on New Zealand's wild west coast, crowded with young men scheming to get rich quick, many of them immigrants from Ireland. While most of the town celebrated St. Patrick's Day that year, a man named Synder Browne huddled in a tent near the muddy outskirts of town, setting type by hand for the first edition of Greymouth's second newspaper, the Evening Star.

Greymouth's first paper, already a year old by then, was the Grey River Argus, which would become a Socialist tabloid. For the next century, the left-wing Argus and the right-wing Star would duke it out in the local marketplace of public opinion; their editors, it was said, took opposing positions on absolutely every public issue. Only once a year, on Christmas Eve, would the two editors get together for a holiday drink and some collegial conversation. Every other day of the year they spat and fussed in the competition for readers and for influence over Greymouth's affairs.

The town survived the gold rush, thanks to another mineral that had actually been discovered earlier but was initially ignored because it didn't glitter like you-know-what: coal. There was plenty of coal in the hillsides around Greymouth, though all the customers for coal, and all the ports suitable for coal shipping, were hundreds or thousands of kilometers away on the other side of the Southern Alps. Greymouth was a seaside town but without a decent harbor; it sat rough and damp in the nearly uninhabited rainforest along the west coast of New Zealand's South Island. To make a go of coal mining thereabouts, somebody was going to have to build a railroad over the mountains.

The Argus and the Star had different ideas about Greymouth's economic development. They argued for different people to pay for, and benefit from, the railroad project. When coal mining became established, the two papers argued even more fiercely over mine safety and environmental issues. The mines there have been productive but quite dangerous, with high concentrations of coalbed methane. Many miners have died over the years in mine fires and explosions, and several mine projects have been abandoned after methane levels proved uncontrollable. The Argus and the Star told different stories about the tragedies.

Most mines are closed now, and the town survives on forestry work and tourism; it is a portal to the glacier and fjord country further south. The population has leveled off at about 5,000, and there's only one newspaper left, the Greymouth Star. The Argus folded in the 1960s.

Today, the Star is owned by a publishing conglomerate based in Dunedin. And even though print media is in big trouble all over the world, the Star is hanging on, with subscribers all along the west coast and a workforce of more than 60 fulltime employees.

The Star is available online as well as on paper. In the latest edition, you can read about Charles Edward Miller Pearce, a New Zealand–born mathematician who taught at Adelaide University in Australia. He came home for a visit, rented a car at the Hokitika airport, just south of Greymouth, then drove south on the coastal highway until he apparently lost consciousness. His car landed upside down in shallow water, with only his head submerged.

"If he had been conscious, all he would have had to do was turn his head towards the middle of the car," a witness told the coroner, according to the Star's report, "and his face would have been out of the water."

"I observed that he had a peaceful expression on his face," noted a second witness. "My guess was that he fell asleep at the wheel and never woke up."

New Zealand

mining

work

history

gold

Greymouth

coal

printing press

newspaper

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Apr 21, 2014

Here in a Zodiac, scooting across Milford Sound, a fjord on New Zealand's remote southwest coast, on a cold wet summer day this past December, is Helen Ruskin Stein Behr with her three sons. Not pictured is her daughter, who visited Milford Sound a few days earlier.

Here in a Zodiac, scooting across Milford Sound, a fjord on New Zealand's remote southwest coast, on a cold wet summer day this past December, is Helen Ruskin Stein Behr with her three sons. Not pictured is her daughter, who visited Milford Sound a few days earlier.

The impetus for the journey to New Zealand was the awesome wedding of one of the granddaughters, Gillian, who emigrated to New Zealand seven years ago with her parents, Richard and Arleigh, and her sister Avi.

Today is Helen's birthday, as she turns eighty-something-and-who's-counting, to our great joy. Wishing her many happy returns of the day.

landscape

New Zealand

Helen

Norman

boat

Bob

rain

Milford Sound

waterfalls

Richard

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Apr 25, 2014

Looks like she's finished her lunch at the Joyful Vegan booth in the Saturday farmers' market next to the train station in Dunedin, New Zealand.

Looks like she's finished her lunch at the Joyful Vegan booth in the Saturday farmers' market next to the train station in Dunedin, New Zealand.

The bumblebees on her left arm raise some interesting issues. Are they about honey and sweetness? Or stinging and pain? Or flight? Or queens or flowers or buzzing or hives?

New Zealand

tattoo

Dunedin

farmers' market

phone

sunglasses

lunch

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Apr 28, 2014

Three hours south of Christchurch on the east coast of New Zealand's South Island is Oamaru, one of the country's oldest cities and briefly–back in the 1870s–one of its wealthiest and fastest growing.

Three hours south of Christchurch on the east coast of New Zealand's South Island is Oamaru, one of the country's oldest cities and briefly–back in the 1870s–one of its wealthiest and fastest growing.

There was a halfway decent harbor for a port to serve the thriving agricultural region, especially after introduction of refrigerated transport for meat. High-quality limestone for building was locally plentiful. A 50-km-long aqueduct was constructed to slake the thirst of the booming little city and irrigate surrounding farmland with fresh mountain water. Industry emerged, lapping up the new water supply. The city built an opera house, an athaeneum, and a large and ornate public garden.

By the 1880s, when economic depression hit hard, Oamaru was said to be "the best built and most mortgaged town in Australasia." The aqueduct went bankrupt, the port closed, industry languished, and construction stopped for more than a hundred years.

What finally saved Oamaru was steampunk, the style of art and/or life that emerged from the punk rock era but is rooted in Victorian-era visions of a fantastic feature: think Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. Steampunk science fiction is inspired by nineteenth-century steam-powered technology and decorative arts, ratcheted up by twenty-first-century irreverence and intensity.

Oamaru's intact nineteenth-century downtown–intact because nobody since the nineteenth century had thought the place worth a dime of investment–created an ideal backdrop for steampunk festivals, steampunk artists' studios, steampunk shopping, and eventually steampunk tourism.

(Oamaru also has penguins, more of which soon. Watch this space.)

New Zealand

train

Oamaru

steampunk

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

May 3, 2014

About forty years ago, the limestone in the old quarry down by the waterfront in Oamaru was finally all worked out. The quarrymen left, taking their big machines with them.

About forty years ago, the limestone in the old quarry down by the waterfront in Oamaru was finally all worked out. The quarrymen left, taking their big machines with them.

The penguins moved in.

Penguins are common in seaside places all over New Zealand, and the Little Blue penguins like the ones in the Oamaru quarry are the commonest of all. New Zealanders generally seem to be fond of penguins and often place nestboxes in their yards to attract them. But city officials in Oamaru felt the town quarry was a terrible spot for a large penguin colony; for one thing, the birds were going to cause all kinds of traffic problems when they went waddling across the roads. For another thing, the quarrying operation had utilized some nasty chemicals, the residue of which might potentially sicken penguins. And then also, of course, somebody might want the real estate to feather his or her own nest, so to speak....

So the birds were moved out, to a site down the coast considered more appropriate. But they came back. Their nests were destroyed, and nice new nestboxes were offered them at the alternative site. They still went back to the quarry. Little Blues do that. They are the smallest of all penguins, not even knee-high, and they are homebodies.

Unlike many species of birds, including several penguin species, Little Blues do not migrate. They settle in communities of hundreds or even thousands of birds, often building their nests within a few feet of the spots where they themselves hatched and were raised.

Every morning, they gather in groups--called rafts--of a dozen or so birds that head down to the beach together and then out into the surf; they swim together for miles to their fishing grounds, where they spread out to spend the day alone, diving a few feet down to catch their favorite fish, a small, shallow-schooling variety called slender sprat.

Penguins have hooks on their beaks and barbs on their tongues, ideal for grabbing onto slippery fishy things.

Every evening, the penguin rafts reassemble and swim back to their home beach, where the birds emerge from the sea and climb back up the bluffs to their nests.

In 1992, the city of Oamaru finally gave up on its penguin-relocation project, perhaps because people had figured out how to monetize the colony. They fenced off the old quarry, opened a gift shop, sold tickets, even built a grandstand so visitors could sit comfortably while they watched the evening parade of feathered finery.

The organization that manages the Oamaru penguin colony also sponsors scientific research into penguin-human interactions. They report that the colony has continued to grow and thrive despite the thousands of tourists tromping through. Breeding pairs currently number about 160, laying between 250 and 500 eggs each spring, of which about 80% will hatch; about 80% of the hatchlings survive to fledge, when they can go out fishing on their own.

The quarry has been cleaned of old industrial waste and outfitted with nestboxes, some of which are designed so that researchers can watch the goings-on inside. And every evening, beginning around sunset, while tour guides keeps the tourists apprised of what the birds are up to, staff members carefully count the number of Little Blues coming back from the sea.

fish

New Zealand

Pacific Ocean

limestone

penguins

Oamaru

quarry

nest boxes

Jun 4, 2014

Girls grooming a very small horse in Gibbston, New Zealand.

Girls grooming a very small horse in Gibbston, New Zealand.

animal

landscape

New Zealand

horse

children

(Image credit: Trey Ratcliff via Stuck in Customs)

Jun 14, 2014

This photo from 1910 will have to speak for itself; we certainly cannot speak for it.

This photo from 1910 will have to speak for itself; we certainly cannot speak for it.

The subject is a butcher shop on the Wadestown Road, in the hills above what is now downtown Wellington, New Zealand. For reasons we cannot begin to fathom, the butchers wear striped aprons, the hog carcasses appear to be decorated, and the local dogs are paying no attention to the meat.

Per Google maps, we can determine that the shop building is still in use today, though no longer as a butcher shop. It's now what New Zealanders refer to as a dairy; Americans would call it a convenience store.

New Zealand

streetscape

1910

Wellington

meat

aprons

shop

butcher

(Image credit: Frederick James Halse via Shorpy)

Jul 18, 2014

A chain of gourmet pizza places in cities around New Zealand's South Island is called Filadelfio's, despite what its website claims as a "New York–inspired atmosphere."

Americans can't help but notice something a little different about the atmosphere, however. Our restaurants have a no-shoes-no-shirt rule, and Kiwi restaurants don't.

New Zealand

restaurant

Oamaru

barefoot

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jul 19, 2014

In the bluffs above the Pacific Ocean on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island is Castlepoint sheep station, a stretch of pastureland as long as Manhattan and half as wide, home to tens of thousands of sheep, a dozen or so sheep dogs, a few thousand head of cattle, a handful of horses, four shepherds with their families, and an American family from Westchester County, New York.

In the bluffs above the Pacific Ocean on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island is Castlepoint sheep station, a stretch of pastureland as long as Manhattan and half as wide, home to tens of thousands of sheep, a dozen or so sheep dogs, a few thousand head of cattle, a handful of horses, four shepherds with their families, and an American family from Westchester County, New York.

Until about twenty years ago, the Americans had been dairy farmers in Westchester, out in the fringes of suburban sprawl. Their small farm attracted the attention of developers, who eventually made them an offer they couldn't refuse; they took the money and headed off to New Zealand, where they bought one of the largest grazing operations in the country, which included beaches, a lighthouse, a big rock so iconic it is featured on the country's postage stamps, and pastures that had been maintained for over a century.

We visited on a difficult day, weaning day. All the little lambs had just been separated from their mothers and herded together into paddocks of their own. The babies were not happy about this, and some were so unhappy they disregarded the electric fences and wandered all alone around the station, looking for mama. The ewes weren't happy either.

sheep

New Zealand

pasture

Masterton

North Island

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jul 21, 2014

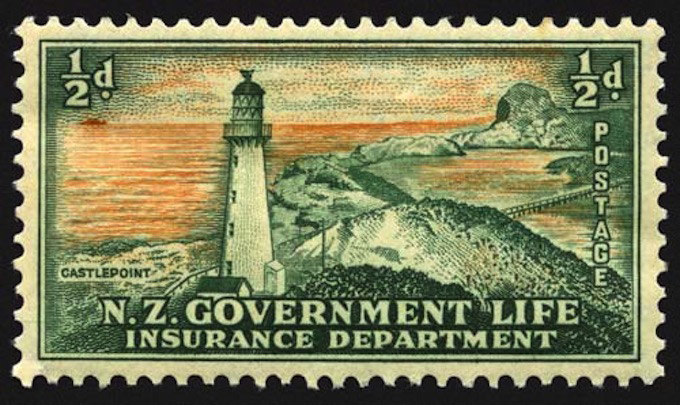

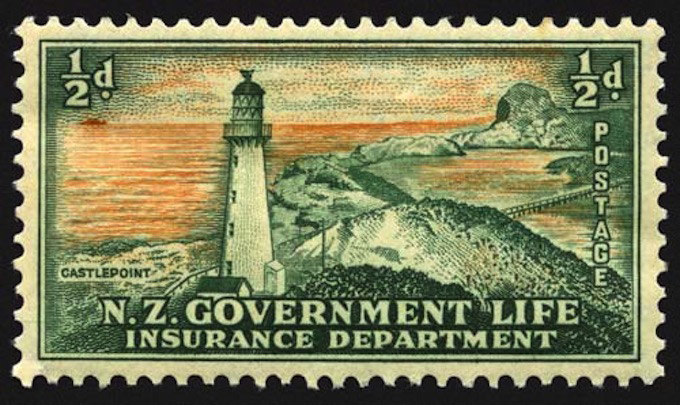

At the north end of Castlepoint sheep station is Castle Rock itself, noted and named in the eighteenth century by Captain Cook. The rock anchors one end of a limestone reef; on the headland at the other end is Castlepoint Lighthouse, built in 1913, originally fueled by oil but now wired into the grid and controlled from a switchboard in Wellington, a couple of hours away. Its light is visible 22 miles out at sea.

The postage stamp above dates from 1947. For almost a century beginning in the 1890s, the New Zealand government operated a life insurance company that had government franking privileges and printed its own stamps. Lighthouses were nineteenth-century symbols for insurance companies (as were big rocks, e.g., Mutual of Omaha). The government sold off its insurance operations in the 1980s, to a corporation doing business as Tower Life of Dunedin, New Zealand.

The reef at Castlepoint is not at all like the coral reefs growing placidly around tropical lagoons; geologically, it's a chunk of ancient seafloor millions of years old heaved up violently during seismic activity associated with the collision of the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates.

The limestone in the reef is richly fossiliferous, and directly underneath the lighthouse it's pocked with caves.

Inside the reef is a lagoon and a wide, hard-sand beach, crucial features in the development of a large sheep station here, back in the days before highways. Since the coast in this region has no natural harbors, sheepmen used to drive wagonloads of wool bales down the beach, to be loaded at water's edge into small boats that ventured out at high tide to meet up with cargo ships waiting offshore.

Today, shipping activity at Castlepoint is mostly recreational in nature, and the hard-packed beach now serves tractors and boat trailers. The blue tractor in the picture below is driverless and remote controlled from the boat, where the captain calls for it to push an empty trailer down into the surf and then pull the loaded trailer back up to high ground.

In the picture below, the tiny figure walking the beach near water's edge is my mother-in-law.

beach

sheep

New Zealand

geology

rock

Pacific Ocean

history

Wairarapa

lighthouse

(Image credit: Little Fuji [lower photo])

Apr 13, 2015

A surprise autumn cold snap attacked New Zealand's South Island this week, with deep snow burying the mountains and lighter snowfalls covering the ground at elevations as low as 100 meters above sea level. This scene was on the road between Mossburn and Te Anau, near New Zealand's southwestern coast.

A surprise autumn cold snap attacked New Zealand's South Island this week, with deep snow burying the mountains and lighter snowfalls covering the ground at elevations as low as 100 meters above sea level. This scene was on the road between Mossburn and Te Anau, near New Zealand's southwestern coast.

According to MetService meteorologist Richard Finnie, the wintry storm was like a bit of June in April: "It's not an early winter," he said, "just an early taste of winter." The cold front was expected to sweep northward across the country and then give way to more normal fall conditions within a few days.

New Zealand

winter

snow

yardscape

swingset

fence

(Image credit: Otago Daily Times)

Apr 21, 2015

The year of earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand, back in 2010 and 2011, left devastation that was still immediately obvious and widespread when we visited in December 2013.

The year of earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand, back in 2010 and 2011, left devastation that was still immediately obvious and widespread when we visited in December 2013.

Many ruined buildings were still propped up then, still awaiting demolition. Some repairs had been begun, some new construction was under way, but the city's main shopping district had been displaced into a new popup mall made out of shipping containers.

Christ Church Cathedral, shown here, once dominated the city's central square. As of this writing, no decision has yet been announced concerning whether to repair or replace or simply demolish what's left of the structure. The new popup Cardboard Cathedral a few blocks away has not officially been designated as a replacement.

New Zealand

cathedral

earthquake

ruins

Christchurch

Christ Church Cathedral

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

They eat guppies in New Zealand.

They eat guppies in New Zealand.

The little guy here in the white apron, with a pencil behind his ear–that's Mr. 4, the grocer-mascot of New Zealand's ubiquitous Four Square chain of supermarkets.

The little guy here in the white apron, with a pencil behind his ear–that's Mr. 4, the grocer-mascot of New Zealand's ubiquitous Four Square chain of supermarkets.

About forty years ago, the limestone in the old quarry down by the waterfront in Oamaru was finally all worked out. The quarrymen left, taking their big machines with them.

About forty years ago, the limestone in the old quarry down by the waterfront in Oamaru was finally all worked out. The quarrymen left, taking their big machines with them.

A surprise autumn cold snap attacked New Zealand's South Island this week, with deep snow burying the mountains and lighter snowfalls covering the ground at elevations as low as 100 meters above sea level. This scene was on the road between Mossburn and Te Anau, near New Zealand's southwestern coast.

A surprise autumn cold snap attacked New Zealand's South Island this week, with deep snow burying the mountains and lighter snowfalls covering the ground at elevations as low as 100 meters above sea level. This scene was on the road between Mossburn and Te Anau, near New Zealand's southwestern coast.