Hole in the Clouds

Sep 15, 2009

It's springtime in New Zealand, time for the Stein sheep to get themselves sheared. Here, Moe is already nekkid, while Curly waits her turn. A., the family shepherdess, says she is "contemplating" learning to spin the wool.

animal

sheep

New Zealand

A.

(Image credit: A. at kiwi-stories)

Sep 17, 2012

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Our newest sheep, Little Fluffy Raincloud, at left in photo, was a gift from a friend of ours. We had three previously, Curly, Lari, and Mow, but Lari died recently of old age and is buried on our property, where she lived a full and happy life. Once your sheep have names, you cannot eat them. We need three sheep to keep the grass in our two paddocks.

The photo below is of our dog, Sesame, who immigrated to New Zealand with us (she is almost 12 now), and Trapper, our New Zealand cat. Both animals regularly follow A. and me when I walk to work in the morning.

Oct 1, 2012

John Stein hasn't written us anything from Seattle, Washington, but he does have pictures to share of his dog, Omar Little.

dog

sheep

animals

window

signage

boston terrier

Omar Little

(Image credits: JJ Stein)

Dec 17, 2012

Not Kilroy, actually, but Ygarzabal, and Laxague and Goytia and Ibarriet. The writing on the trees is perfectly clear, if you can read Euskara, the Basque tongue: "Felix Arospide was here in 1897." "Josto Sarria, August 1962."

Not Kilroy, actually, but Ygarzabal, and Laxague and Goytia and Ibarriet. The writing on the trees is perfectly clear, if you can read Euskara, the Basque tongue: "Felix Arospide was here in 1897." "Josto Sarria, August 1962."

"Long live the sheepherders," proclaims a tree in Elko County, Nevada, "the ones who can take this place."

Wherever there have been sheep in the mountainous parts of the American West, there have been sheepherders from the Basque country of Europe. And for well over a century now, in the aspen groves at the edges of high country sheep meadows, names and dates and drawings and even poetry have been carved into the aspens, some of the text in Spanish, a little in French, but much in Euskara, a language long forbidden by government officials back home in France and Spain.

Gora Euskadi! read many of the inscriptions. "Long live the Basques."

But a more common carving is Biba ni! "Hooray for me."

And most common of all are sentiments along these lines: "Hooray for the whores of America. Long live the whores of Biscay as well!"

Most Basque shepherds in the United States were not shepherds back in Europe, and Basque people back in Europe did not carve pictures and smutty sayings into the bark of Basque trees. In America, however, the loneliness and tedium of life in the wilderness with sheep led resourceful people to innovate. For example, on a mountainside above Lake Tahoe, at the edge of a meadow with a multi-million-dollar view, a shepherd took his knife to a large aspen and inscribed: "I'm bored and we sheepherders lack a woman."

Aspen trees live no more than about eighty years, and the trees selected for carving were usually large and already mature. Old-style sheepherding ended in America around 1970, so most of the Basque carvings are dead or dying now, falling to the ground and rotting.

"I am not coming back here," says one sun-bleached log near a Montana lake. "Except to fish, maybe."

sheep

Nevada

Sierra Nevadas

Basque

Tahoe

shepherds

herders

aspen

arborglyph

West

carving

Jan 26, 2014

This is not, of course, a New Zealand sheep; it's a Dutch sheep, trimmed to look not so much like a sheep, at the behest of Amsterdam artists Lernert & Sander, who'd been hired by a newspaper to illustrate a series on the theme of family.

This is not, of course, a New Zealand sheep; it's a Dutch sheep, trimmed to look not so much like a sheep, at the behest of Amsterdam artists Lernert & Sander, who'd been hired by a newspaper to illustrate a series on the theme of family.

Human families, needless to say, have black sheep. What about black sheep families? It took dog groomer Marieke Hollander almost a full day to do up this sheep like a French poodle, but the result was, at least arguably, quite a black sheep among black sheep.

animal

sheep

Holland

Marieke Hollander

grooming

poodle?

DeVolkskrant

(Image credit: Lernert & Sander)

Mar 5, 2014

Lupin–from North America–and gorse–from Europe–are valued plants in much of the northern hemisphere. They were intentionally imported into New Zealand, lupin as a showy garden flower, gorse as a golden-blooming hedgerow plant to help farmers establish the boundaries of their pastures.

Lupin–from North America–and gorse–from Europe–are valued plants in much of the northern hemisphere. They were intentionally imported into New Zealand, lupin as a showy garden flower, gorse as a golden-blooming hedgerow plant to help farmers establish the boundaries of their pastures.

Both plants grew well in New Zealand and quickly became naturalized, spreading across much of the countryside, crowding out native bush, reducing habitat for native animals, and eventually finding themselves on the official registry of invasive species and noxious weeds.

Gorse is much the worse offender, now occupying 5 percent of New Zealand's land area and virtually impossible to eradicate. In Europe, gorse thickets are functional living fences around fields and pastures. The hedgerows break up areas of agricultural monoculture, providing habitat for wild birds and other native critters, and the thorny branches help farmers keep "wild" animals out of the fields and grazing animals in place. In New Zealand, however, gorse jumps right out of any hedgerows, displaces both native plants and cultivated crops, and swallows up all the open land thereabouts, till there's no grass left for the sheep and cattle. In just a few years, a gorse infestation can reduce pastureland and cropland to worthless, thorny scrub that is highly prone to catching fire.

Gorse seeds survive for many years in the soil near their parent plants. If the plants are pulled out or killed, the seeds immediately germinate in the disturbed soil and quickly, vigorously, happily replace whatever gorse has been laboriously removed.

Lupin too, is happy in its adopted New Zealand home (even though Kiwis drop the "e" that Americans just know belongs at the end of the plant's name). The lupin species that has made itself at home in so much of the country is Russell lupin, native to western North America and noted for the range of color on its spectacular flower spikes. Russell lupin likes conditions in New Zealand so well it has learned to thrive there even in places without soil, such as in the wide open gravel beds of the South Island's famed braided rivers.

Braided rivers are actually a rare kind of habitat, found in Alaska, western Canada, New Zealand's South Island, and very few other places. They flow steeply down from rapidly eroding mountains, carrying lots of sediment but not much water except during spring snowmelt, when the gravel is scoured clean. During times of low water, shallow streams and pools meander through the gravel, habitat for rare birds and fish. But when lupin colonize a braided river, the dense mats of their roots and stems trap sediment, choking off the riverwater, pinching its flow into relatively deep, narrow, fast-flowing channels that native fish and birds can't survive in.

Lupin spreads across a braided riverbed at the rate of about two meters a year. And the riverwater washes the lupin seeds downstream, to begin new colonies.

The photo at the top of this posting shows both lupin and gorse becoming established at the edge of a braided river near Arthur Pass.

Photo 1 below: Gorse has conquered the hillside at left in the Taieri Gorge west of Dunedin and is spreading to still-pastoral hillsides in the photo's background.

Photo 2: A sheep picks its way between thorny gorse bushes in a pasture with little grass left to eat.

Photo 3: Beautiful lupin grows dreamily in the highlands around Lake Tekapo.

Possible error message: We are decidedly non-expert in the art and science of plant identification. What we claim is gorse in the photos here may actually be one or more of several vaguely gorse-like species, perhaps Scotch broom, which is also an invasive noxious weed, or perhaps a native Kiwi type of broom, which is not considered weedy at all because it keeps to its place in the ecological scheme of things.

sheep

New Zealand

flowers

plants

invasive species

braided river

Jul 19, 2014

In the bluffs above the Pacific Ocean on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island is Castlepoint sheep station, a stretch of pastureland as long as Manhattan and half as wide, home to tens of thousands of sheep, a dozen or so sheep dogs, a few thousand head of cattle, a handful of horses, four shepherds with their families, and an American family from Westchester County, New York.

In the bluffs above the Pacific Ocean on the east coast of New Zealand's North Island is Castlepoint sheep station, a stretch of pastureland as long as Manhattan and half as wide, home to tens of thousands of sheep, a dozen or so sheep dogs, a few thousand head of cattle, a handful of horses, four shepherds with their families, and an American family from Westchester County, New York.

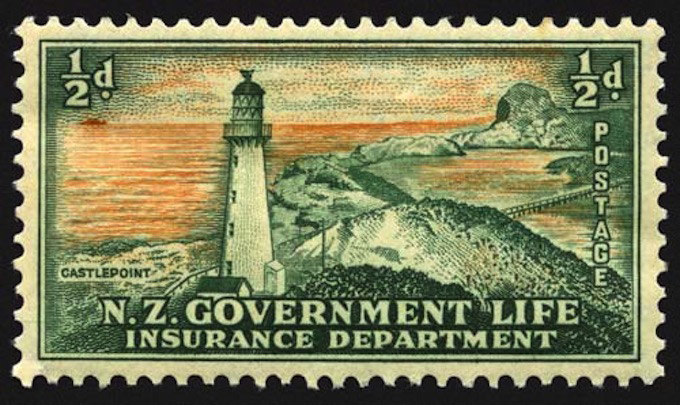

Until about twenty years ago, the Americans had been dairy farmers in Westchester, out in the fringes of suburban sprawl. Their small farm attracted the attention of developers, who eventually made them an offer they couldn't refuse; they took the money and headed off to New Zealand, where they bought one of the largest grazing operations in the country, which included beaches, a lighthouse, a big rock so iconic it is featured on the country's postage stamps, and pastures that had been maintained for over a century.

We visited on a difficult day, weaning day. All the little lambs had just been separated from their mothers and herded together into paddocks of their own. The babies were not happy about this, and some were so unhappy they disregarded the electric fences and wandered all alone around the station, looking for mama. The ewes weren't happy either.

sheep

New Zealand

pasture

Masterton

North Island

(Image credit: Little Fuji)

Jul 21, 2014

At the north end of Castlepoint sheep station is Castle Rock itself, noted and named in the eighteenth century by Captain Cook. The rock anchors one end of a limestone reef; on the headland at the other end is Castlepoint Lighthouse, built in 1913, originally fueled by oil but now wired into the grid and controlled from a switchboard in Wellington, a couple of hours away. Its light is visible 22 miles out at sea.

The postage stamp above dates from 1947. For almost a century beginning in the 1890s, the New Zealand government operated a life insurance company that had government franking privileges and printed its own stamps. Lighthouses were nineteenth-century symbols for insurance companies (as were big rocks, e.g., Mutual of Omaha). The government sold off its insurance operations in the 1980s, to a corporation doing business as Tower Life of Dunedin, New Zealand.

The reef at Castlepoint is not at all like the coral reefs growing placidly around tropical lagoons; geologically, it's a chunk of ancient seafloor millions of years old heaved up violently during seismic activity associated with the collision of the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates.

The limestone in the reef is richly fossiliferous, and directly underneath the lighthouse it's pocked with caves.

Inside the reef is a lagoon and a wide, hard-sand beach, crucial features in the development of a large sheep station here, back in the days before highways. Since the coast in this region has no natural harbors, sheepmen used to drive wagonloads of wool bales down the beach, to be loaded at water's edge into small boats that ventured out at high tide to meet up with cargo ships waiting offshore.

Today, shipping activity at Castlepoint is mostly recreational in nature, and the hard-packed beach now serves tractors and boat trailers. The blue tractor in the picture below is driverless and remote controlled from the boat, where the captain calls for it to push an empty trailer down into the surf and then pull the loaded trailer back up to high ground.

In the picture below, the tiny figure walking the beach near water's edge is my mother-in-law.

beach

sheep

New Zealand

geology

rock

Pacific Ocean

history

Wairarapa

lighthouse

(Image credit: Little Fuji [lower photo])

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

Richard Stein writes from Lower Hutt, New Zealand:

This is not, of course, a New Zealand sheep; it's a Dutch sheep, trimmed to look not so much like a sheep, at the behest of Amsterdam artists Lernert & Sander, who'd been hired by a newspaper to illustrate a series on the theme of family.

This is not, of course, a New Zealand sheep; it's a Dutch sheep, trimmed to look not so much like a sheep, at the behest of Amsterdam artists Lernert & Sander, who'd been hired by a newspaper to illustrate a series on the theme of family.