Hole in the Clouds

Aug 4, 2009

For another entry in our occasional series on post-Soviet public art, consider this monument, erected in 2007 in Moscow, thonoring the Nobel-prize-winning author Mikhail Sholokhov.

There must be something about the situation of this monument that makes it difficult to photograph the whole thing at once. I've settled here for a picture that shows barely more than half of it--missing off to the right is most of a stone pedestal supporting a rowboat carrying a bronze statue of Sholokhov himself. That's the bow of the boat and the curve of Sholokhov's back at the right edge of the photo. He is just sitting in the boat, not rowing.

The boat and the swimming horses are not directly from any of his novels, I'm told. Note that there are two groups of horses, both apparently trying to swim upstream but veering off in slightly different directions. One group is reddish in color, the other whitish. This has all been described as a metaphor for the Russian Revolution, in which Sholokhov fought as a 13-year-old boy on the side of the reds. His most famous novel, And Quiet Flows the Don, looks at life among the Cossacks of his native Rostov-on-Don region of Russia in the years leading up to World War I and the Russian Civil War and revolution. If the river is representing time or history, it is surely significant that Sholokhov is facing bacward in the boat.

The monument is the work of a committee: artist Alexander Rukavishnikor, architect Igor Voskresensky, and sculptors Iulian and Philip Rukavishnikov.

Sholokhov is something of a Soviet success story. Although the revolution ended his formal schooling at the age of 13 and he suppored himself in the early 1920s as a stevedore, he decided to become a writer and took advantage of writers' seminars offered for workers.. His mother, a Ukrainian, was illiterate until late in life, when she decided to learn to write letters to her son.

Perhaps the greatest feud of Soviet literary history involved Sholokhov and Aleksandr Solzhenitzsyn, who despised one another. Sholokhov wrote a scathing review of Solzhenitzsyn's work, and Solzhenitzsyn accused Sholokhov of plagiarism. Many Moscow residents dislike the monument intensely--Sholokhov had nothing to do with Moscow, they say, and should not be memorialized in the city--certainly not on the street named Gogol Boulevard, The underlying issue seems to be that he's a Soviet author, and these latter days are a problematic time for monuments to Soviet authors.

Soviet art

Russia

Moscow

Mikhail Sholokhov

Aleksandr Solzhenitzsyn

(Image credit: Susan Wiggin)

Oct 12, 2009

Those amongst us who are not artists nonetheless feel we know a thing or two about art and artists. We "know" that artistic vision and style are intensely personal, that "art by committee" is doomed to fail. But see here, "Morning in a Pine Forest," painted in 1886 by Russian artists Ivan Shishkin and Konstantin Savitsky.

Shishkin and Savitsky were both accomplished painters and well-regarded at the time. Shishkin was known for sweeping landscapes that portrayed the Russian countryside in loving detail. Savitsky painted sentimental tableaux, often of historical scenes. They both signed this painting, and for years it was assumed that the forest was by Shishkin and the bears by Savitsky.

But archivists eventually discovered preliminary sketches for the work done by both men, and it became clear that each of them contributed to both the background and the bears. Meanwhile, for unknown reasons, the first owner of the painting ordered that Savitsky's signature be removed from the canvas.

Whatever. It's a nice picture.

Russia

Morning in a Pine Forest

art

Konstantin Savitsky

Iran Shishkin

Nov 2, 2009

Ivan Shishkin painted this field of ripened rye in 1878. The grain is so tall it almost hides a couple of people way in the distance, on the road near the middle of the picture. I'm pretty sure that they are hunters; there are two dead birds at the edge of the field in the foreground, and a big flock of birds still in the sky.

I love this painting. I might not have fallen for it so completely if I'd noticed the dead birds first, but it's too late now. I love how simple it is: field, trees, road--something we might see any time we go out into the country. Not a specially scenic spot. But the trees are super trees, bigger and more dramatic than ordinary trees. The crop in the field is golden, bursting-ripe. The road reels us in, winding mysteriously. They say Shishkin painted this way to celebrate the bounty of Russian nature. He knew what he was doing.

landscape

Russia

art

Ivan Shishkin

Nov 6, 2009

During last year's Republican convention, when Sarah Palin was first introduced to the world outside Alaska, many Americans in the lower forty-eight or forty-nine began to google her name obsessively, desperate to find out who on earth she was. Political bloggers in Alaska rose to the challenge, and some of them developed loyal followings from far outside Alaska, even after Sarah Palin stepped offstage and went off tiptoeing through the tulips.

Among the best and most successful of the Alaska bloggers is a woman who calls herself Mudflats. Grateful readers of her work--Mudpuppies--recently presented her with a handmade quilt celebrating the world she has written about online. Each quilt square is centered on a pair of boots, the better for traipsing through the muck of politics. This "I can see Russia from my airspace!" square memorializes one of Palin's more notorious stupidities from the 2008 campaign.

Mudflats continue to blog, bringing humor and enthusiasm to discussions of life in Alaska and politics in Washington or wherever. She speaks up especially for the downtrodden, for people we tend to overlook or shove aside, perhaps because they live in villages at the furthest extremes of the Alaskan bush, where nobody but Mudflats bothers to see the tough times in their airspace.

Russia

Sarah Palin

Alaska

(Image credit: Mudflats)

Dec 30, 2009

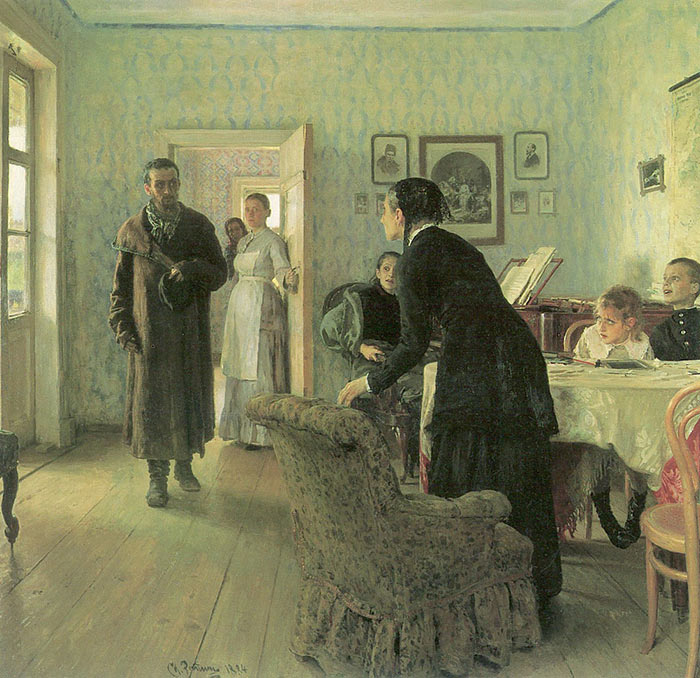

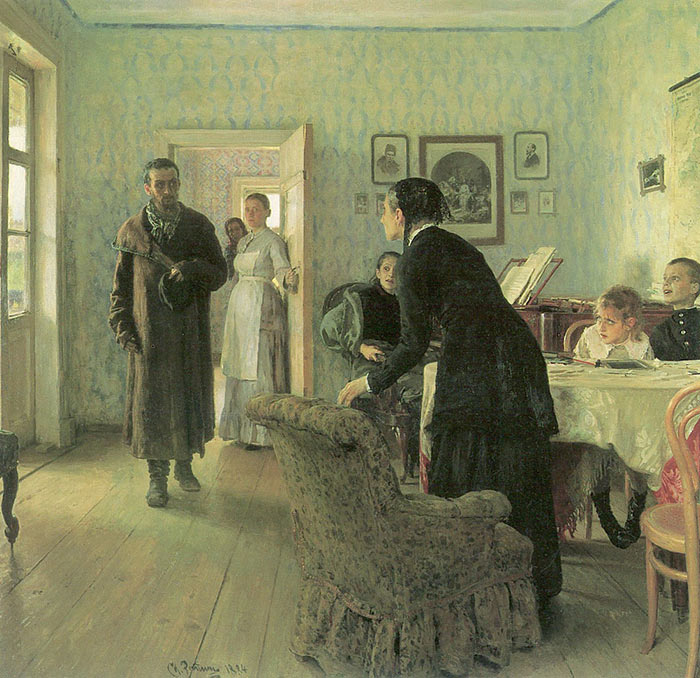

They Didn't Expect Him, by Ilya Serin, 1883. A revolutionary returns home unexpectedly from political exile, setting up a cinematic sort of family scene.

The man's mother rises to greet him. The little girl, his younger child, seems a little frightened; perhaps he has been gone so long that she doesn't recognize him. The boy, a little older, looks thrilled. The man's wife, sitting at the piano near the door, is startled and confused; perhaps she had given him up for lost. Perhaps too, she has been angry about his political obsessions that left the family abandoned for so long. The servants are watchful, eager to see what happens next.

The man himself looks haggard and unsure of himself. His return is not triumphant; perhaps it's not anything at all like what he might have imagined while he was away. Can he pick up the pieces of his old life? Will his wife welcome him back? What about his political and intellectual life, which had led to his exile? What does he do now?

painting

Russia

art

Ilya Serin

Feb 17, 2011

At the extreme Pacific end of Russia, north of China and Korea and Japan, the volcanoes of the Kamchatka Peninsula are erupting again.

At the extreme Pacific end of Russia, north of China and Korea and Japan, the volcanoes of the Kamchatka Peninsula are erupting again.

This is nothing new; the 29 volcanoes of Kamchatka’s mountainous spine—10 percent of the world’s active volcanoes—have erupted prodigiously and often for at least the last two million years.

Since October, three of them have been seriously erupting, spewing ash 32,000 feet into the sky and devastating their surroundings with earthquakes, lava flows, mudslides, and pyroclastic catastrophe. Shown here is last week’s eruption of Shiveluch, the northernmost of the currently active volcanoes. This picture is thermal imagery from satellite sensors; the hottest areas are shown as white, with progressively less hot regions appearing as gradations of yellow through orange to red.

Shiveluch had a lava dome near its peak—a rocky bulge inflated by molten magma underground. This thermal image tells us that the dome has now burst; the white splotch at the mountain peak shows extremely hot lava exposed at the surface. The rock that used to overlie the lava dome would have been pulverized in the eruption and sent skyward as ash or down the mountainside as a pyroclastic flow, a fiery nightmare of lava, ash, rock, mud, and poisonous gases.

The image also shows a large pool of hot lava that has collected at the bottom of the mountain, beginning to cool off around the edges. Undoubtedly, forest land in this valley has been devastated, but because the Shiveluch region is virtually uninhabited, damage associated with human activity is expected to be very low.

However, planes traveling between Alaska and Korea or Japan often fly just east of Kamchatka. The dust plumes from Shiveluch and the other two currently active volcanoes have sometimes been large enough to pose a potential risk to aviation.

This video from last October, when the level of activity was not yet as intense, shows both the ash clouds rising and the lava descending from Shiveluch:

Russia

volcano

Shiveluch

Kamchatka

(Image credit: NASA ASTER sensors on TERA satellite)

Jul 21, 2011

Where in the world?

Where in the world?

This is Barnaul, a city of 800,000 in Siberia, located deep in the heart of central Asia, near the mountain range where Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and China come together.

Barnaul grew large and relatively wealthy because of its double-edged location: close to the Altai Mountains, with their riches of silver, copper, and other minerals, but far from the rest of the world. During World War II, the Soviet Union relocated many of its munitions industries to Barnaul, safely distant from the front but close to major railroads that had been built for ore transport. Russia's largest ammunition plant, one of the largest in the world, still operates today in Barnaul.

The downtown area of the city doesn't look like this; it was modeled after Saint Petersburg and is known for handsome classical architecture, a sampling of which I will try to post here soon. But around the edges of town, in amongst the old silver-smelting factories and the ore-loading facilities, what we see here is what we get in twenty-first-century Barnaul.

cityscape

Russia

Siberia

mining

skyscrapers

Altai Krai

Barnaul

(Image credit: Surovy mag (

Dec 9, 2011

The satellite view of Philadelphia in infrared, from a few days ago, led some people to ask for more false-color imagery of our planet. Here we've got a river delta in the tundra of eastern Siberia, where the River Lena empties into the Arctic Ocean. The image is from mid-summer, when the plants of the tundra were bursting with new growth, thanks to twenty-four hours a day of sunlight. The color scheme here is different from that of the Philadelphia scene but still not closely related to the colors a human eye would detect. The data displayed comes from three sensors on the Landsat satellite: one that detects infrared energy, another that detects near-infrared energy, which is very sensitive to the chemicals associated with growing vegetation, and a third sensor that picks up a part of the visible spectrum. Vegetation is green, exposed rock or soil is pink, wet soil (mud) is purple, and ice is blue.

Even in mid-summer, the sea ice floats close to shore. It will take another month or two for most of the ice to melt and/or wash out to sea, but as soon as it does freezing temperatures will return and ice formation will begin again.

The innumerable ponds and distributary streams are typical of flat places throughout the Arctic tundra, where permafrost just below the surface impairs drainage. Meltwater and rainwater sit on top of the permafrost all summer long, breeding mosquitoes...... which don't show up in the satellite imagery.

birdseye view

Russia

infrared

Siberia

remote sensing

tundra

Landsat

Lena River

delta

river

Arctic Ocean

Jan 9, 2012

The Petrovsky-Palace-on-the-way was built in 1782 so that Catherine the Great and her entourage would have a place to stop and rest up on the last night of what was then an arduous seven-day journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow.

The Petrovsky-Palace-on-the-way was built in 1782 so that Catherine the Great and her entourage would have a place to stop and rest up on the last night of what was then an arduous seven-day journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow.

According to the intertubes, she spent only a single night there, in 1785. Napoleon also spent a night at the palace, in 1812, while hiding from the fires that were raging through Moscow. Throughout the nineteenth century, czars and emperors used Petrovsky Palace as a staging site from which their coronation processions headed to the Kremlin.

After the revolution, the Soviets rebuilt all the imperial palaces in the Moscow area except for this one, which was preserved on the grounds of the top-secret Zhukovsky Military-Engineering Academy of Aviation. After perestroika it came into the hands of the city government, which recently restored and reopend Petrovsky Palace as a guest house and reception center for VIPs visiting Moscow.

Russia

Moscow

Catherine the Great

Petrovsky Palace

Napoleon

(Image credit: Fedor Vilnor)

Mar 11, 2012

This early twentieth-century advertising placard recommends drinking Georges Borman cocoa if you want to be big and strong.

This early twentieth-century advertising placard recommends drinking Georges Borman cocoa if you want to be big and strong.

Russia

advertising

lion

muscles

Mar 20, 2012

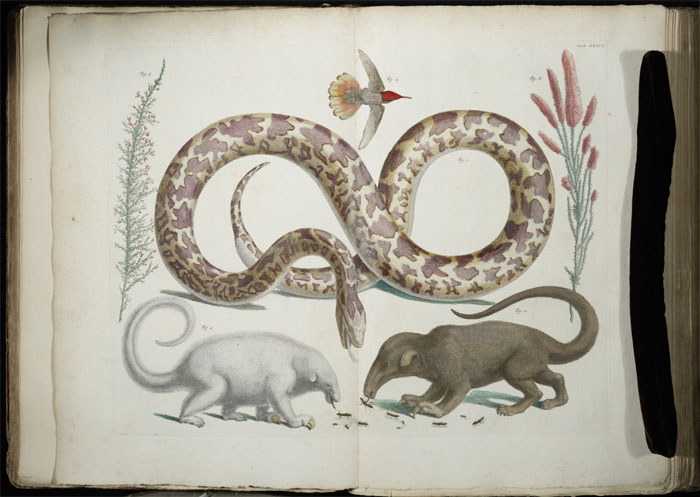

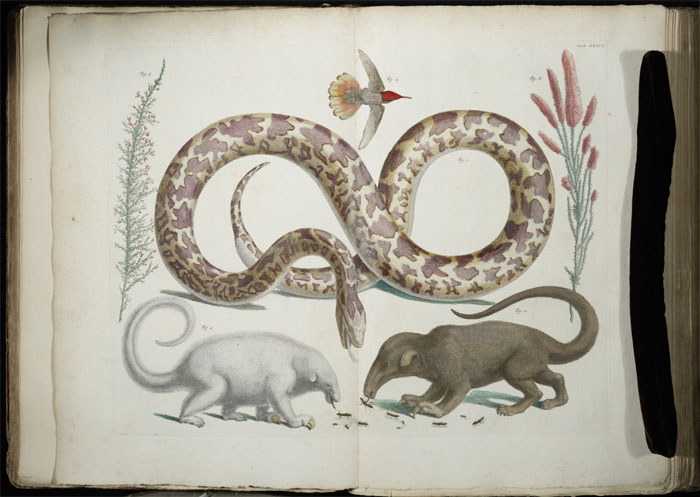

In hopes of fostering the development of medical science in Russia, Peter the Great scoured the West for natural history objects: taxidermy, live birds and insects, botanical and anatomical illustrations, and paraphernalia associated with monsters. Albertus Seba, a wealthy Dutch pharmacist and traveler, had amassed the largest natural history collection of the mid-18th century. Peter bought all of Seba's objects and library, including this book of colored zoological plates, and installed everything in St. Petersburg, where it became the nucleus of the Russian national collections.

In hopes of fostering the development of medical science in Russia, Peter the Great scoured the West for natural history objects: taxidermy, live birds and insects, botanical and anatomical illustrations, and paraphernalia associated with monsters. Albertus Seba, a wealthy Dutch pharmacist and traveler, had amassed the largest natural history collection of the mid-18th century. Peter bought all of Seba's objects and library, including this book of colored zoological plates, and installed everything in St. Petersburg, where it became the nucleus of the Russian national collections.

The book is currently in the Spencer Research Library at the University of Kansas.

Russia

animals

Peter the Great

18th century

natural history

Albertus Seba

(h/t: bibliodyssey2lj)

Sep 9, 2012

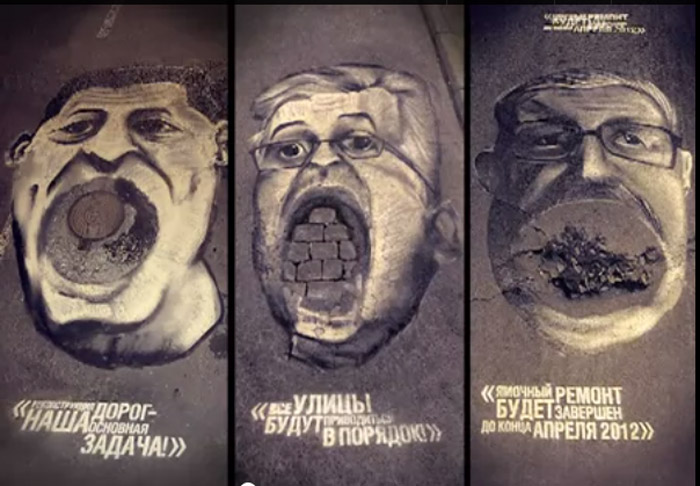

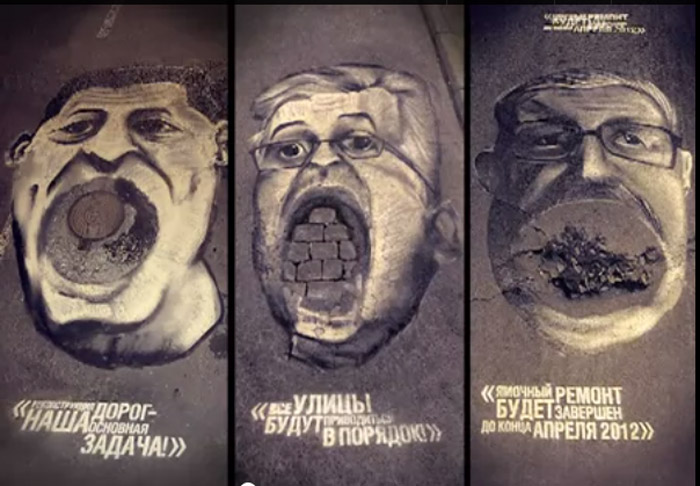

We all know that artists are often politically minded people, and that much art is intended, on some level or another, to communicate political ideas. But we all also know that works of political art, regardless of whether or not they succeed artistically, usually fail to directly accomplish much of anything politically. The paintbrush is not often mightier than the sword.

We all know that artists are often politically minded people, and that much art is intended, on some level or another, to communicate political ideas. But we all also know that works of political art, regardless of whether or not they succeed artistically, usually fail to directly accomplish much of anything politically. The paintbrush is not often mightier than the sword.

A couple of months ago, artwork on the streets of Yekaterina, Russia, a city of almost two million people about a thousand miles east of Moscow, got the political job done. The city fathers of Yekaterina–the regional governor, the mayor, and the vice-mayor–had all been elected on promises to repair potholes and other problems in the city's badly deteriorating roadways. Once in office, however, they seemed to lose interest; despite citizen complaints, the potholes just kept getting worse and worse.

One dark night in July, Yekaterina artists took to the streets of center city and painted portraits of the three well-known politicians with wide-open mouths surrounding three of the worst potholes. They documented their work with a video that they posted to a popular local website; an English-language video about their video is here.

The next day, the potholes were fixed and the portraits scrubbed from the pavement. Officials denied that the artwork had anything to do with the sudden burst of municipal maintenance.

Yekaterina was already a city with a certain artistic sensibility; in addition to their potholes, the downtown streets feature a bronze monument to Michael Jackson.

Russia

art

streetscape

politics

action

Yekaterinburg

Sverdlovsk Oblast

(ura dot ru via thisiscolossal dot org)

Dec 25, 2012

When the Cold War thawed, old Russian cultural traditions became new again, and Ded Moroz–Father Frost–emerged from hiding up near the Siberian part of the North Pole to resume his holiday responsibilities.

When the Cold War thawed, old Russian cultural traditions became new again, and Ded Moroz–Father Frost–emerged from hiding up near the Siberian part of the North Pole to resume his holiday responsibilities.

To acknowledge the new cultural politics, Ded Moroz's many colleagues in northern and eastern Europe–notably Joulupukki, Finland's Christmas Goat–now seek him out at border crossings and Christmas markets across the continent. The two Nicks typically engage in a little winter diplomacy, sometimes competing in endeavors such as chimney climbing.

This picture features Ded Moroz presenting a gift to Joulupukki during a diplomatic mission in Minsk, capital of Belarus.

Incidentally, Ded Moroz can sleep in Christmas morning, because in Russia, the gift thing doesn't happen till New Year's. Happy New Year's one and all......

Russia

Belarus

holiday

Christmas

Finland

(h/t: Katrin Maldre)

Jan 15, 2013

The Russian painter Ivan Shishkin was illustrating scenery in Poland in 1890, when he completed this painting of the swampy forests of the Pripyat, or Rokitno, marshland. Today, the spot where he set up his easel could be in Ukraine or Belarus or Russia or perhaps extreme eastern Poland.

The Russian painter Ivan Shishkin was illustrating scenery in Poland in 1890, when he completed this painting of the swampy forests of the Pripyat, or Rokitno, marshland. Today, the spot where he set up his easel could be in Ukraine or Belarus or Russia or perhaps extreme eastern Poland.

But the scene he painted may or may not look much the same. The marshes of Polessia remained lightly settled throughout much of the twentieth century; the forests there provided years of cover for partisans fighting for and against the Nazis and the Soviets.

Then came the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986, which devastated much of the countryside, leaving large stretches radioactive and uninhabitable. Not all the wildlife has returned. Although herons have again been reported, "mushrooms and berries," it is said, "set Geiger counters screaming."

landscape

Russia

Belarus

Ukraine

birds

1890

Poland

great blue heron

Russian painting

marshland

Pripyat Marsh

(Art by Ivan Shishkin)

Apr 9, 2013

Climate change–both the literal thaw in the Siberian permafrost and the political thaw in the Cold War militarization that long controlled life in the Soviet Arctic–is currently exposing long-frozen tusks of ancient wooly mammoths to the light of day and the vicissitudes of the global economy.

Climate change–both the literal thaw in the Siberian permafrost and the political thaw in the Cold War militarization that long controlled life in the Soviet Arctic–is currently exposing long-frozen tusks of ancient wooly mammoths to the light of day and the vicissitudes of the global economy.

Until the end of the last ice age, around 10,000 years ago, woolly mammoths ranged the grasslands of eastern Siberia. As the icecaps melted and sea level rose, the grasslands became forest or were submerged in the Arctic Ocean, until hungry mammoths were eventually crowded together on isolated islands in the eastern Arctic. The last of them died there about 3,500 years ago.

A mammoth tusk like this one, which weighs 150 pounds, can sell for $60,000 in the Siberian town of Yakutsk, and it may fetch $200,000 or more in the ivory markets of China.

Each summer, thawing permafrost exposes more tusks in gravelly riverbanks and seaside bluffs, especially on remote, uninhabited islands north of easternmost Siberia. Each spring, Yakut tusk-hunters cross the frozen sea to begin searching for the new "crop" of ivory; they work alone or in small crews, living on scant rations in rough huts, until late-summer snowstorms once again hide their quarry.

The unlucky ones leave then, returning home emptyhanded in small boats in rough waters. The lucky ones hang on for a few more weeks, however, till the ocean freezes again and they can transport their tusks much more easily in sledges hauled by snowmobiles.

Russia

Siberia

climate

prehistory

tusk

wooly mammoth

(Image credit: Nat'l Geographic online)

Mar 10, 2017

When the snow starts to melt in Yaroslavl, Russia, the city's famed Assumption Cathedral shows up in the slush.

When the snow starts to melt in Yaroslavl, Russia, the city's famed Assumption Cathedral shows up in the slush.

Russia

Assumption Cathedral

Yaroslavl

(Image credit: Nik2)

This early twentieth-century advertising placard recommends drinking Georges Borman cocoa if you want to be big and strong.

This early twentieth-century advertising placard recommends drinking Georges Borman cocoa if you want to be big and strong. In hopes of fostering the development of medical science in Russia, Peter the Great scoured the West for natural history objects: taxidermy, live birds and insects, botanical and anatomical illustrations, and paraphernalia associated with monsters. Albertus Seba, a wealthy Dutch pharmacist and traveler, had amassed the largest natural history collection of the mid-18th century. Peter bought all of Seba's objects and library, including this book of colored zoological plates, and installed everything in St. Petersburg, where it became the nucleus of the Russian national collections.

In hopes of fostering the development of medical science in Russia, Peter the Great scoured the West for natural history objects: taxidermy, live birds and insects, botanical and anatomical illustrations, and paraphernalia associated with monsters. Albertus Seba, a wealthy Dutch pharmacist and traveler, had amassed the largest natural history collection of the mid-18th century. Peter bought all of Seba's objects and library, including this book of colored zoological plates, and installed everything in St. Petersburg, where it became the nucleus of the Russian national collections. We all know that artists are often politically minded people, and that much art is intended, on some level or another, to communicate political ideas. But we all also know that works of political art, regardless of whether or not they succeed artistically, usually fail to directly accomplish much of anything politically. The paintbrush is not often mightier than the sword.

We all know that artists are often politically minded people, and that much art is intended, on some level or another, to communicate political ideas. But we all also know that works of political art, regardless of whether or not they succeed artistically, usually fail to directly accomplish much of anything politically. The paintbrush is not often mightier than the sword. When the Cold War thawed, old Russian cultural traditions became new again, and Ded Moroz–Father Frost–emerged from hiding up near the Siberian part of the North Pole to resume his holiday responsibilities.

When the Cold War thawed, old Russian cultural traditions became new again, and Ded Moroz–Father Frost–emerged from hiding up near the Siberian part of the North Pole to resume his holiday responsibilities.

Climate change–both the literal thaw in the Siberian permafrost and the political thaw in the Cold War militarization that long controlled life in the Soviet Arctic–is currently exposing long-frozen tusks of ancient wooly mammoths to the light of day and the vicissitudes of the global economy.

Climate change–both the literal thaw in the Siberian permafrost and the political thaw in the Cold War militarization that long controlled life in the Soviet Arctic–is currently exposing long-frozen tusks of ancient wooly mammoths to the light of day and the vicissitudes of the global economy.