Spring Back

Apr 30, 2012

It was springtime, and we were young. I'm thinking it was 1984 in Decatur, Georgia, and Joe was about eighteen months old, Ted about three and a half, and I was a spring chicken myself.

It was springtime, and we were young. I'm thinking it was 1984 in Decatur, Georgia, and Joe was about eighteen months old, Ted about three and a half, and I was a spring chicken myself.

Apr 30, 2012

It was springtime, and we were young. I'm thinking it was 1984 in Decatur, Georgia, and Joe was about eighteen months old, Ted about three and a half, and I was a spring chicken myself.

It was springtime, and we were young. I'm thinking it was 1984 in Decatur, Georgia, and Joe was about eighteen months old, Ted about three and a half, and I was a spring chicken myself.

Aug 19, 2014

Somewhere near this scene, just out of camera range, there's probably an old inscription scratched by a pocketknife into a barn rafter: "Norman Rockwell was here."

Somewhere near this scene, just out of camera range, there's probably an old inscription scratched by a pocketknife into a barn rafter: "Norman Rockwell was here."

It's Minnesota in the springtime. You can tell it's Minnesota because the little boy with his back to the camera is still wearing his winter hat, with the earflaps folded up.

The photographer is not known, but there's a caption written on the Kodachrome slide: "Dam at Blue Earth, just below the cemetery, May 4, 1952."

Mar 26, 2016

Apr 7, 2016

Inside the screened porch in Columbia, Missouri, are tulips, safe from the deer. Outside in the yard is a homemade wood-fired bread oven.

Inside the screened porch in Columbia, Missouri, are tulips, safe from the deer. Outside in the yard is a homemade wood-fired bread oven.

Apr 25, 2016

In the mid-nineteenth century, the area around the northern Japanese city of Towada was designated as imperial ranchland, devoted to raising horses for the samurai cavalry.

The most famous of these horses was probably First Frost, which Emperor Hirohito rode for propaganda purposes during World War II. The U.S. Navy claimed to confiscate First Frost but actually left it with Hirorhito's personal property. Admiral "Bull" Halsey had promised to ride Hirorhito's horse when the Americans arrived in Tokyo, so another all-white horse was substituted for a ceremonial ride through town, for propaganda purposes.

Towada recalls its heritage with bronze horses spilling out onto a main street designated officially as Government Administration Road, nicknamed Horse Road. There are also 151 cherry trees along the road.

Apr 29, 2016

This tulip, with its "broken" coloration of creamy white petals edged in deep crimson, attracted the highest price ever bid for a tulip bulb during Holland's seventeenth-century frenzy of speculation in tulips.

This tulip, with its "broken" coloration of creamy white petals edged in deep crimson, attracted the highest price ever bid for a tulip bulb during Holland's seventeenth-century frenzy of speculation in tulips.

In a January 1637 auction, an anonymous bidder was willing to spend 5,500 florins for a single Semper Augustus bulb, enough money to buy a large house on a fashionable canal in Amsterdam and more than five times the amount of Rembrandt's commission for his masterpiece The Night Watch. The Semper Augustus tulips, widely illustrated at the time as exemplars of the pinnacle of floral beauty, were maddeningly rare because a mysterious collector was thought to be hoarding the bulbs.

The collector rejected the high bid at this auction, and within a month, the tulip bubble had collapsed. It is not known what happened to the Semper Augustus, which vanished long ago from the tulip world. Quite possibly, the variety died out because of infection with a virus spread by aphids, which we now know accounts for broken color patterns in tulips but also tends to weaken their growth over multiple generations.

Like so much else in life, whether associated with flowers or with finance, it was nice while it lasted.

Feb 20, 2017

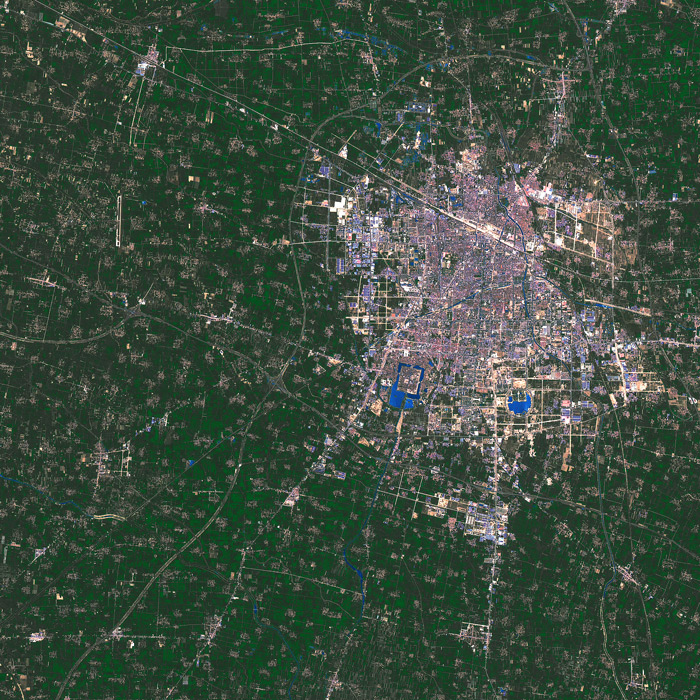

On the morning of May 13, 2016, NASA's Landsat 8 satellite collected thermal, infrared, and visible-light data from high above the city of Shangqiu, home to more than 1.5 million people in the midst of the wheat, cotton, corn and sesame fields of the North China Plain.

On the morning of May 13, 2016, NASA's Landsat 8 satellite collected thermal, infrared, and visible-light data from high above the city of Shangqiu, home to more than 1.5 million people in the midst of the wheat, cotton, corn and sesame fields of the North China Plain.

Shangqiu is a transportation hub, located at the junction of China's major north-south and east-west railroads. Also, the largest frozen-food processing company in China is headquartered there.

The lush agricultural land surrounding the city shows up as deep green in this image because Landsat's sensors are particularly sensitive to the vigorous plant growth characteristic of freshly planted fields in mid-spring.

The small brownish blotches in the farmland are agricultural villages. Almost 6 million people live in villages in the Shangqiu hinterland.

Mar 19, 2017

My sister Carol is hard at work on a sewing card, in our front yard in Silver Spring, Maryland, circa 1958.

Back in the day, little girls and perhaps also some boys "sewed" around the pictures on these cards as an introductory activity intended to help prepare us for real sewing. Carol was probably three or four when she threaded the shoelace-tipped yarn through holes punched in the card; by age five or six, she had probably moved up to simple cross-stitch embroidery using real needles and thread and tiny, child-sized thimbles. All that stuff is out of fashion now, though the old cards, sometimes called lacing cards, are still available on ebay and etsy. Maybe the whole sewing thing is just too girly for modern parents. Or too 1950s.

I never was much of a girly girl, but I really loved sewing cards and cross stitch, and I kept begging and begging my mother to teach me how to use her sewing machine. As soon as I started to learn, however, I gave it all up for good. It turned out that real sewing involved ironing each seam as you went along–and I hated, hated, hated ironing. Also, sewing under my mother's eye required doing the stitches properly–in other words, I had to rip out most of my attempts at seams and do them over and over again.

But Carol was and still is good with her hands. For her, the sewing cards may have served as preparation for piano lessons, or for penmanship at school. But isn't this activity more suitable for work indoors, sitting down on the floor or at a table? I'm guessing Carol put her sweater on and brought the card outside so our father could take a picture without a flashbulb.