Hole in the Clouds

Nov 29, 2009

Bring Your Own Water.

The sun in Namibia is so harsh, according to photographer Vincent Mounier, that picture-taking during the day yields nothing but bleached, blasted-to-white landscapes. At dusk and dawn, however, the earth reclaims its colors, and the eyes can open wide for a long, calm look.

landscape

Namibia

desert

(Image credit: Vincent Mounier)

Jun 1, 2012

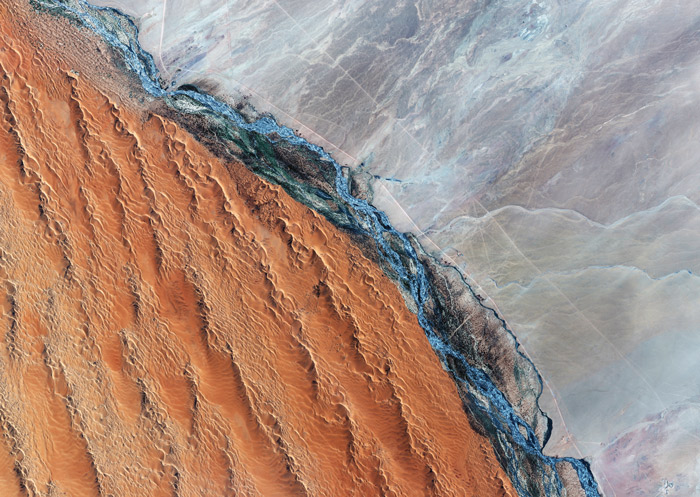

Southern Namibia, as seen from the Landsat 7 satellite orbiting 700 kilometers above the earth's surface.

Southern Namibia, as seen from the Landsat 7 satellite orbiting 700 kilometers above the earth's surface.

birdseye view

Namibia

desert

satellite imagery

remote sensing

wilderness

(Image credit: NASA Landsat 7)

Oct 13, 2013

Well, of course now that our American space program is shut down because of hateful people in the House of Representatives, the brand new Landsat 8 satellite that you and I paid for, which had just started phoning in dramatic new views of our planet, has gone dark. But fortunately, many other countries have legislatures that don't seem to go quite so insane over efforts to help people get medical care, and so new earth imagery from foreign satellites is still available to us.

Well, of course now that our American space program is shut down because of hateful people in the House of Representatives, the brand new Landsat 8 satellite that you and I paid for, which had just started phoning in dramatic new views of our planet, has gone dark. But fortunately, many other countries have legislatures that don't seem to go quite so insane over efforts to help people get medical care, and so new earth imagery from foreign satellites is still available to us.

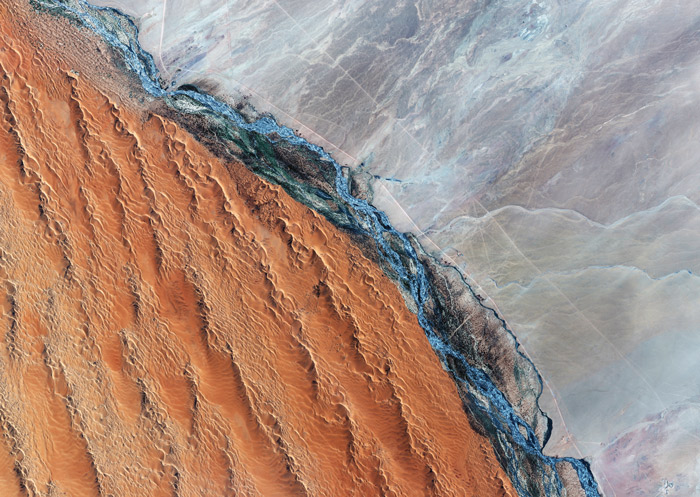

This is the view from Kompsat 2, a Korean satellite, as it crossed southern Africa above the Namib Desert on the morning of October 5. What appears to be blue water is actually an ancient riverbed, almost entirely dry for millions of years; the white streaks are bone-dry salt flats.

Click to zoom in and see roads in the riverbed and some black dots that represent the only vegetation for hundreds of square miles; These desert shrubs survive on groundwater, of which there is hardly any; such as is there is, however, collects deep underneath the riverbed, below the gullies where water does trickle on those rare occasions when it rains here. Annual precipitation is less than half an inch on average, though it is supplemented a bit by coastal fog.

Note the short spur leading off the main road near the middle of the scene and ending at the base of a dune. This is the route to a parking lot at Dune 45, a thousand-foot high sand dune popular with tourists.

birdseye view

Namibia

desert

space

remote sensing

Africa

satellite

Korea

(Image credit: Kompsat 2 via European Space Agency)

Mar 20, 2018

The Kuiseb River flows–when it flows–down from the highlands of eastern Namibia and across the Namib Desert toward the Atlantic Ocean.

The Kuiseb River flows–when it flows–down from the highlands of eastern Namibia and across the Namib Desert toward the Atlantic Ocean.

South of the river, some of the highest sand dunes on earth are blown ever northward by the prevailing winds, but the sand can't cross the river. North of the river is a vast plain of bare rock, much of it billions of years old, Precambrian, predating the emergence of life.

The river itself, like many desert rivers, is ephemeral, flowing briefly after rains. The rains come–if they come–in January, February, or March. By April, the riverbed is dry. Even so, scrubby vegetation has taken hold along its banks.

Sand from the dunes is literally choking off the river. The river water, which often is not much more than a trickle, has to carry heavy loads of sand from upstream, traveling in a riverbed already piled high with sand blown in during the dry season, on top of sand left behind in previous years by the slow, struggling current.

There is so much sand now in the Kuiseb River that most years the water can no longer reach the sea. Only extreme flooding can push river water all the way to the river's mouth at Walvis Bay on Namibia's Atlantic Coast; the last time this happened was in 1963, though the river came within a few kilometers of the sea in 1997 and might have made it all the way but for a hastily bulldozed artifical sand dune blocking its path to protect the salt works at Walvis Bay.

Namibia

Precambrian gneiss and schist

Kuiseb River

ephemeral river

sand dunes

Namib Desert

(Image credit: GeoEye 1 satellite)

Southern Namibia, as seen from the Landsat 7 satellite orbiting 700 kilometers above the earth's surface.

Southern Namibia, as seen from the Landsat 7 satellite orbiting 700 kilometers above the earth's surface.