Mar 15, 2010

The little country store in northern Minnesota that Mom and Pop were keeping in 1937, when photographer Russell Lee happened by for the Farm Security Administration, was once a big and bustling emporium. Back in 1910, it had employed eight clerks, plus a butcher and a bookeeper. But in 1923, the nearby iron mine closed, and the Vermilion Range mining town known as Section 30 quickly became a ghost town, as weather-beaten and empty as Cripple Creek and the other more famous ghost towns out west.

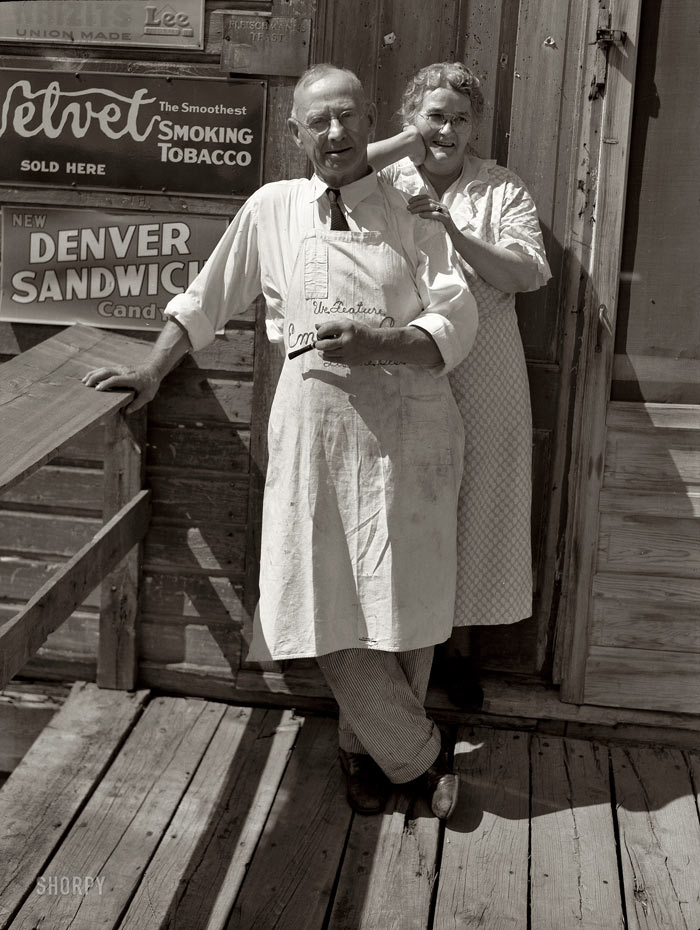

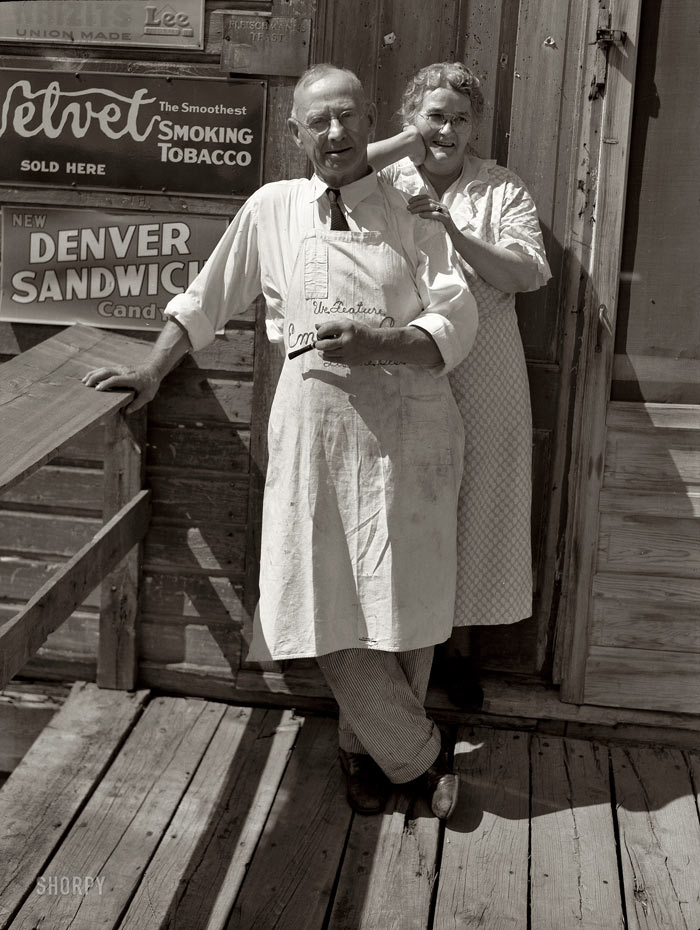

When this photo was taken, the mine had been closed and the town abandoned for fifteen years. The photographer noted that the town of Section 30 was "bust." How, then, are Mom and Pop getting by? The store building is being kept up, the storekeepers are eating somehow. They look cheerful and relaxed, not at all like the haunted, haggard figures in so many Depression-era images.

I don't really know the answer. There were seasonal logging camps in the Section 30 area, but they were probably too isolated to reliably support even a little crossroads store. No new economic activity ever sprang up to replace the old mine; today, there's nothing but woods in that neck of the woods, plus some rusted old mining machinery.

Iron ore was identified in Section 30 back in the 1880s. Two groups of men tried to claim the property and mineral rights, using two different strategies to get title to the land. One group went to the nearest courthouse, in Duluth, and bought the land with "Sioux half-breed scrip"--currency issued to Indians for land transactions with the government; the men had bought the scrip from Indians who had nothing to do with the land. A second group of men filed homesteading claims on the land and built houses there to prove up their claims. The two groups sued one another, and to pay for the lawsuits, they had to bring in extra partners, including an ex-congressman. The competing claims dragged through the courts until 1902, when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Indian-scrip group (which included the ex-congressman); the homesteaders' claim was invalidated because homesteaders are not allowed to sign contracts conveying partial ownership of the land until their claims are proven up, even though such contracts had been necessary in order to defend the claims in court.

The mine turned out to be even richer than anticipated; the motherlode was just eight feet below the surface. Active mining began in 1903, and the town of Section 30 filled up overnight. Twenty years later, the boom went bust, yet fifteen years into the bust, here are Mom and Pop making a living and a life, somehow, in Section 30.

Minnesota

Section 30

Vermilion Range

1937

store

(Image credit: Russell Lee, FSA)

May 8, 2011

The Mississippi River is flooding now, cresting at Memphis near record levels and adding water from swollen tributaries as it rolls on south toward New Orleans.

The Mississippi River is flooding now, cresting at Memphis near record levels and adding water from swollen tributaries as it rolls on south toward New Orleans.

By all accounts, flood crests along the southern part of the river will reach the highest levels ever recorded during the next ten days or so. Although little new rain is expected, snow melt from up north plus spring rains totaling 400 percent of normal throughout broad stretches of the Midwest and South have filled the river system far beyond capacity.

The worst recorded Mississippi floods–probably the worst single disaster in American history–came in 1927, when levees were overtopped and undermined in literally hundreds of places, stranding more than a million people in high water, many of them for three months or longer. Among the ironies of this disaster is its hero, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, who organized rescue and relief operations that were so impressive his performance propelled him all the way to the presidency the next year, in which office he stood idly by while the country sank into the Great Depression.

Depression-era public works projects improved the levees and supplemented them with floodways–gates in the levees opening onto back channels that could be intentionally flooded when necessary, taking pressure off the levees during high water. But the water ran even higher in 1937 than in 1927, and again almost a million people were flooded out of their homes. Among the ironies this time: the rains that caused this flood were what finally put an end to the long Dust Bowl drought.

Again, flood defenses were strengthened, and the next time the river ran really, really high, in 1973, flooding was severe but not catastrophic. However, the 1973 floodwater did damage the "Old River Control Structure," shown here, which is key to the entire lower Mississippi Valley as we know it–and which is at risk now, in the highest flood the river has ever seen.

The Old River Control Structure is a Rube Goldberg sort of complex designed to keep the Mississippi River from abandoning its channel and finding a new route to the Gulf of Mexico. Like all rivers, the Mississippi constantly tries to create new distributaries near its mouth, where it has deposited so much sediment that it's blocking its own flow. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Army Corps of Engineers helped this process along by dredging new channels to shorten shipping routes and removing huge logjams that trapped river sediment. Year after year, more and more of the Mississippi left its banks and drained west through the Atchafalaya swamp, eventually reaching the Gulf near Morgan City, Louisiana, far to the west of New Orleans and the current river delta.

The Atchafalaya swamp drainage eventually scoured out a river channel, which could efficiently drain even more of the Mississippi water. Scientists predicted that by 1980, the entire river would reroute itself into the Atchafalaya basin, permanently flooding Morgan City and other communities near the swamp. The cities of New Orleans and Baton Rouge, with their huge ports, refineries, and other industries, would no longer be connected by a deepwater river to the rest of the country; a little water would still travel in the old riverbed, but it would become brackish, shallow, and slack, like all the other Gulf of Mexico bayous.

This would be economically devastating to the region and perhaps to the entire country, since we would lose massive amounts of petroleum and transportation infrastructure. New Orleans and environs would lose their drinking water and much of their economic function. The entire population of Morgan City would have to be relocated.

To prevent all this catastrophe, Congress passed a law against the Mississippi changing its course. Literally, the law requires that at least 70 percent of the river water stay in the current river channel all the way to the Gulf of the Mexico; only 30 percent can legally flow the way it now wants to flow, to the west through the Atchafalaya.

To enforce this law, the Corps of Engineers built the Old River Control Structure, which partially failed in the 1973 flood. They reinforced the original structure and added new auxiliary features to help out. The question now is whether this new control system can stand up to the record-level flooding of 2011.

If it fails, the lower Mississippi will most likely never again return to its banks. Already, in the forty years since the Control Structure went into effect, Mississippi mud deposited by the riverwater has built up the Mississippi's bed near Old River till it is about five or six feet higher than the Atchafalaya river there; a hydroelectric power plant has been built on site to take advantage of the elevation drop, and a lock and dam had to be built to handle ship traffic. Obviously, if the river there were left to its own devices, it would respond to gravity like any other river and dive over this five-foot drop, hurrying along to the Gulf of Mexico, New Orleans be damned.

The key metric is three million cubic feet per second; that's the "project flood," the maximum flow the Old River Control Structure was built to handle. It's not been tested at anything close to that level; it will be tested now, beginning around May 19. We can hope.

The video below shows images from the 1937 flood, to the song by Johnny Cash recalling his boyhood experience of that flood in Dies, Arkansas.

music

1937

flood

Johnny Cash

1927

video

Mississippi River

2011

The Mississippi River is flooding now, cresting at Memphis near record levels and adding water from swollen tributaries as it rolls on south toward New Orleans.

The Mississippi River is flooding now, cresting at Memphis near record levels and adding water from swollen tributaries as it rolls on south toward New Orleans.