Hole in the Clouds

Dec 3, 2010

The best singer from my neighborhood here in Philadelphia might be the best singer ever from any neighborhood anywhere: Marian Anderson. A future Good Morning will look at her in the neighborhood; for now, let's get straight to the singing.

We remember Marian Anderson as the artist-entertainer who first broke through the color line in 1930s America. We do not remember her the way she appears in this Richard Avedon photo from much later in her life; she was not the sort of woman who let her hair down in public, literally or figuratively.

Maybe she looked a little like this sometimes down in the basement of the South Philadelphia rowhouse she bought with the earnings from her European concert tours, a basement in which she installed a piano and a champagne cooler and extra soundproofing in the walls. But even in her private music-making, it is hard to imagine her settling for anything less than, or straying very far from, the highest standards of Western highbrow music. Her training had been hard to come by, but she had mastered her art like nobody before or since. That's what Arturo Toscanini said after listening to her in Vienna, and it's what Jean Sibelius said when he begged her to let him write a song for her.

Seventy-five thousand Americans, white and black, gathered outside the Lincoln Memorial on a cold April morning in 1939 to hear Marian Anderson sing for them. Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt had arranged the concert after the Daughters of the American Revolution had refused to let her perform in their hall, which like all accommodations in Washington back then was completely segregated. She would go on to sing at the inaugurations of presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy, and in 1963 she returned to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to sing for hundreds of thousands of Americans at Martin Luther King, Jr.'s, march on Washington.

You can hear her sing at these and other events, from the 1920s through the 1960s, on YouTube. Even though the quality of the recordings is sometimes disappointing and the highbrow diction characteristic of the era's artists can be distracting, you'll hear a voice so silky and deep and glowing that it hurts.

She performed classical recital songs and operatic arias, and her rendition of Schubert's "Ave Maria" was particularly beloved, even though she was an alto, not a soprano. Her concerts also included "Negro spirituals," to which she applied her professional training; she didn't let loose with them but stayed cleanly loyal to the melody, performing them just as carefully and elegantly as she did her European art music. Nobody sings those songs that way any more, but Marian Anderson could pull it off.

Here she is singing "You hear de lambs a-cryin."

Philadelphia

Marian Anderson

Stanton School

Daughters of the American Revolution

Union Baptist Church

racism

Jean Sibelius

Eleanor Roosevelt

Arturo Toscanini

(Image credit: Richard Avedon)

Jun 27, 2012

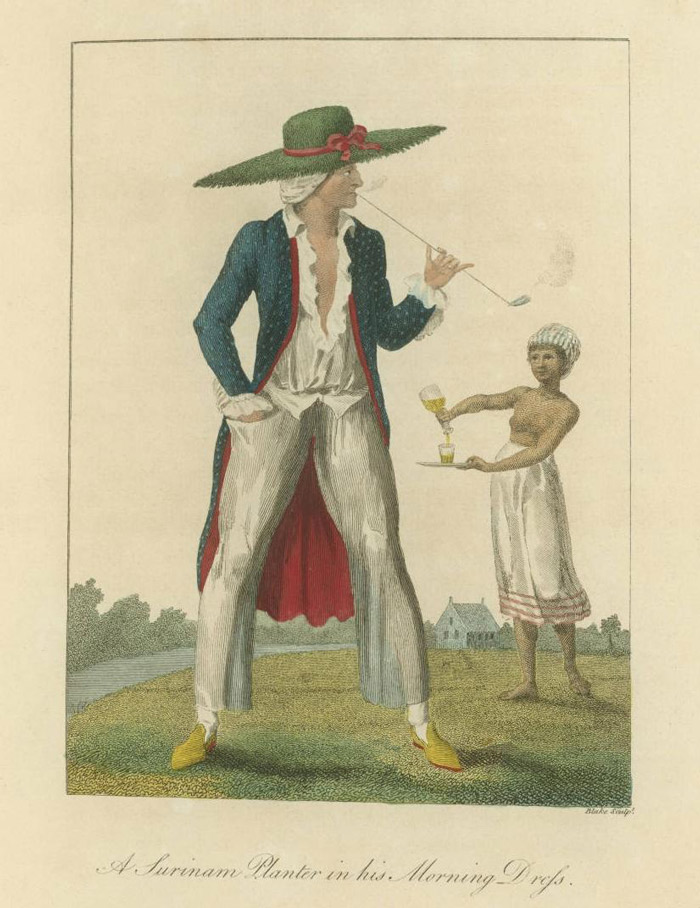

This 1796 engraving, "A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress," is from an etching by William Blake, based on a sketch by John Gabriel Stedman. Stedman spent five years in Surinam in the 1770s as an officer in a troop of 800 European mercenaries hired by the Dutch to suppress marauding bands of escaped slaves, who were hiding in the swamps and rainforest at the periphery of plantation lands and raiding the plantations in search of provisions, weapons, and new escapees.

This 1796 engraving, "A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress," is from an etching by William Blake, based on a sketch by John Gabriel Stedman. Stedman spent five years in Surinam in the 1770s as an officer in a troop of 800 European mercenaries hired by the Dutch to suppress marauding bands of escaped slaves, who were hiding in the swamps and rainforest at the periphery of plantation lands and raiding the plantations in search of provisions, weapons, and new escapees.

The military mission was a failure; more and more slaves fled the plantations, casting their fate with the maroons, as the escaped slaves were called. In response, the planters of Surinam attempted to impose more and more draconian discipline--though obviously, as this picture suggests, they exempted themselves entirely from any discipline whatsoever.

The planter's "morning dress" consists of his nightclothes, robe, and slippers, plus a ridiculous sunhat. He had to get up early and go out for a stroll across the grounds of his plantation in order to supervise the flogging of his slaves, a daily routine considered critical to plantation life. Stedman believed that the beatings were particularly brutal in Surinam, partly because many slaves were believed to be aiding and abetting the maroons and partly because a lively slave trade from Africa provided ready replacements for anyone crippled or killed by the overseer's lash.

To fortify the planter for his morning ritual, a slave hovers nearby with a carafe of wine. Alcohol and tobacco would presumably get him through this rough assignment, until he can go back to the house and change out of these workclothes to prepare for the social rounds that would occupy the remainder of his day.

During John Stedman's years in Surinam he became increasingly critical of the social structure his soldiers were fighting to uphold; the slaves were severely mistreated, and the planters were dissolute and worthless. Stedman recounts that he fell in love with a beautiful woman in Surinam, a slave named Joanna; he arranged for her emancipation, and they married and had a son, Johnny Stedman. But John Stedman Sr. eventually returned to Europe without Joanna or Johnny, claiming that Joanna refused to go to a land where she knew she would not be welcomed. She died a few years later, and Johnny was sent to England to live with his father, who had already remarried and begun a second family.

By all accounts, John Stedman favored Johnny over the children he had with his new wife, who refused to accept Johnny into the household. The boy was sent to boarding school and eventually joined the British navy as a midshipman. He was still a teenager when he died at sea.

His father, meanwhile, wrote up his recollections of Surinam and submitted them for publication, along with sketches that were parceled out among professional engravers, including William Blake. The book was an international bestseller, translated into five languages. Blake and Stedman became good friends, though philosophically they had almost nothing in common.

As much as Stedman despised the life he saw in Surinam, he clung to a belief that some form of slavery could be not only moral but necessary. Only after his death was a chapter about Joanna excerpted from his book and published as an abolitionist pamphlet.

racism

slavery

Surinam

John Gabriel Stedman

Johnny Stedman

white men can't jump

1796

colony

plantations

(Image credit: William Blake)