Hole in the Clouds

Dec 14, 2010

In the 1850s, John Brown announced to trusted friends and family that he'd been chosen by God to end slavery in the United States. He traveled first to Kansas, where abolitionists and slave-holding settlers were battling for control of the territory. Then he went to Canada to raise money, gather supporters, and lay plans for an uprising.

In October 1859 Brown returned to the United States with a couple of dozen men, white and black, and a plan to organize slave revolts in the mountainous regions of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. From mountain hideouts, abolitionist bands would help slaves attack their masters and conduct guerilla-style warfare against slaveholders and their civilization.

Brown's first target was the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, in what is now West Virginia. The men were already well armed, thanks to donations from abolitionists, but additional weapons would be needed to arm the hundreds or thousands of slaves that were expected to join the revolt. Brown's raiders cut the telegraph line, took hostages including George Washington's nephew, captured a train on the B&O railroad line that passed through town, and took the armory.

But the ultimate success of the plan depended on sparking a general rebellion of slaves throughout the area, which never happened. After a few hours, U.S. Marines led by Robert E. Lee and Jeb Stuart arrived from Washington; Stuart attempted to negotiate a surrender but when Brown refused, the raid was put down in literally three minutes.

During those three minutes, Brown was severely wounded by a sword blow, from which he never recovered. At his trial for treason he lay on a stretcher and barely participated in the proceedings. He was hanged on December 2, 1859.

Slaves did not join him in revolt, but they sang about his body, mouldering in the dust, and about his soul, marching on. Less than two years later, civil war engulfed the whole country, and less than two years after the war began, Lincoln proclaimed that slaves were free.

The military commanders who had quashed Brown's raid at Harpers Ferry, Lee and Stuart, resigned their commissions in the U.S. Army and fought for the Confederacy.

This image of Brown's warriors approaching the Harpers Ferry arsenal is from a 1941 series of twenty-two paintings by Harlem artist Jacob Lawrence that illustrate the life and legend of John Brown.

West Virginia

John Brown

abolition

terrorism

Harper's Ferry

slavery

(Painting by Jacob Lawrence)

Jun 27, 2012

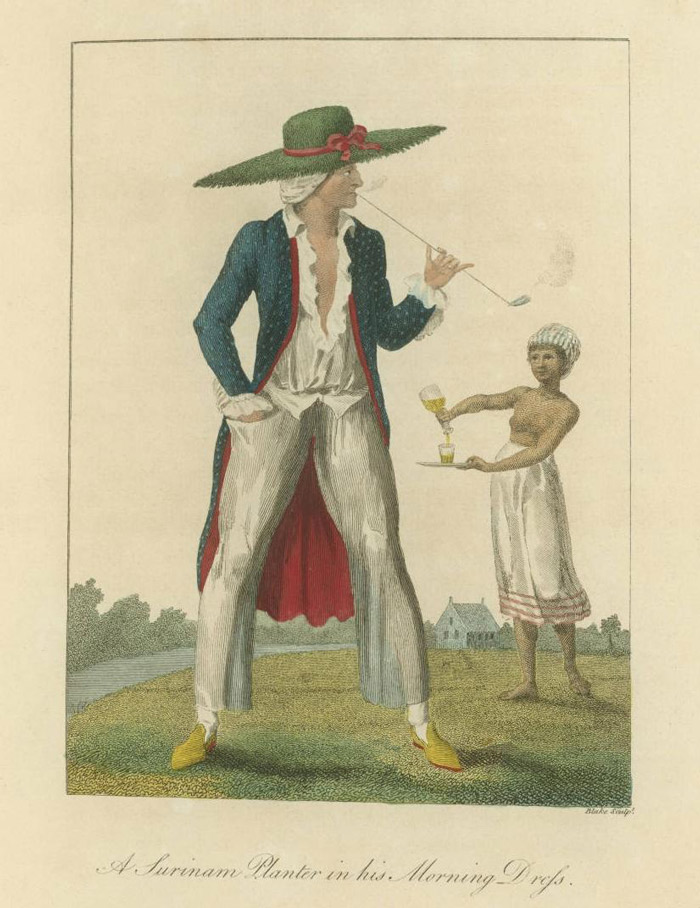

This 1796 engraving, "A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress," is from an etching by William Blake, based on a sketch by John Gabriel Stedman. Stedman spent five years in Surinam in the 1770s as an officer in a troop of 800 European mercenaries hired by the Dutch to suppress marauding bands of escaped slaves, who were hiding in the swamps and rainforest at the periphery of plantation lands and raiding the plantations in search of provisions, weapons, and new escapees.

This 1796 engraving, "A Surinam Planter in his Morning Dress," is from an etching by William Blake, based on a sketch by John Gabriel Stedman. Stedman spent five years in Surinam in the 1770s as an officer in a troop of 800 European mercenaries hired by the Dutch to suppress marauding bands of escaped slaves, who were hiding in the swamps and rainforest at the periphery of plantation lands and raiding the plantations in search of provisions, weapons, and new escapees.

The military mission was a failure; more and more slaves fled the plantations, casting their fate with the maroons, as the escaped slaves were called. In response, the planters of Surinam attempted to impose more and more draconian discipline--though obviously, as this picture suggests, they exempted themselves entirely from any discipline whatsoever.

The planter's "morning dress" consists of his nightclothes, robe, and slippers, plus a ridiculous sunhat. He had to get up early and go out for a stroll across the grounds of his plantation in order to supervise the flogging of his slaves, a daily routine considered critical to plantation life. Stedman believed that the beatings were particularly brutal in Surinam, partly because many slaves were believed to be aiding and abetting the maroons and partly because a lively slave trade from Africa provided ready replacements for anyone crippled or killed by the overseer's lash.

To fortify the planter for his morning ritual, a slave hovers nearby with a carafe of wine. Alcohol and tobacco would presumably get him through this rough assignment, until he can go back to the house and change out of these workclothes to prepare for the social rounds that would occupy the remainder of his day.

During John Stedman's years in Surinam he became increasingly critical of the social structure his soldiers were fighting to uphold; the slaves were severely mistreated, and the planters were dissolute and worthless. Stedman recounts that he fell in love with a beautiful woman in Surinam, a slave named Joanna; he arranged for her emancipation, and they married and had a son, Johnny Stedman. But John Stedman Sr. eventually returned to Europe without Joanna or Johnny, claiming that Joanna refused to go to a land where she knew she would not be welcomed. She died a few years later, and Johnny was sent to England to live with his father, who had already remarried and begun a second family.

By all accounts, John Stedman favored Johnny over the children he had with his new wife, who refused to accept Johnny into the household. The boy was sent to boarding school and eventually joined the British navy as a midshipman. He was still a teenager when he died at sea.

His father, meanwhile, wrote up his recollections of Surinam and submitted them for publication, along with sketches that were parceled out among professional engravers, including William Blake. The book was an international bestseller, translated into five languages. Blake and Stedman became good friends, though philosophically they had almost nothing in common.

As much as Stedman despised the life he saw in Surinam, he clung to a belief that some form of slavery could be not only moral but necessary. Only after his death was a chapter about Joanna excerpted from his book and published as an abolitionist pamphlet.

racism

slavery

Surinam

John Gabriel Stedman

Johnny Stedman

white men can't jump

1796

colony

plantations

(Image credit: William Blake)